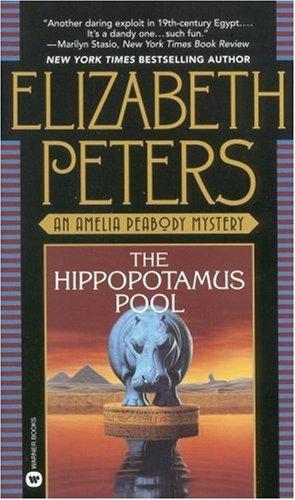

The Hippopotamus Pool

Read The Hippopotamus Pool Online

Authors: Elizabeth Peters

Tags: #Mystery & Detective - General, #Detective, #Detective and mystery stories, #Mystery & Detective, #Mystery, #Fiction - Mystery, #General, #Egypt, #Suspense, #Women Sleuths, #Historical, #Large Type Books, #Fiction

THE HIPPOPOTAMUS POOL

Elizabeth Peters

Book 8

CHARACTERS APPEARING OR

REFERRED TO IN THE HIPPOPOTAMUS POOL

Abd el Hamed—antiquities dealer and forger, living in Gurneh Abdullah ibn Hassan al Wahhab—reis (foreman) of Emerson's Egyptian workmen

Ali—a suffragi (room steward) at Shepheard's Hotel Ali, Mohammed, Selim, et cetera et cetera—Abdullah's sons, who also work for the Emersons

Ali Murad—antiquities dealer and American consular agent in Luxor Amherst, William—Cyrus Vandergelt's assistant, a young Egyptologist, who has very little to do with the story Bertha—a woman of mystery, one of the Emersons' former enemies Brugsch, Emile—assistant to Maspero, first archaeologist to enter the cache of royal mummies at Deir el Bahri Budge, Wallis—Keeper of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities at the British Museum; notorious for his questionable methods of acquiring objects for the museum

Carter, Howard—newly appointed Inspector of Antiquities for Upper Egypt Daoud—Abdullah's nephew Emerson, Amelia Peabody—Victorian gentlewoman, archaeologist, and expert in crime

Emerson, Evelyn—Walter's wife, granddaughter of the late Earl of Chalfont Emerson, Radcliffe—Amelia's husband, "the most eminent Egyptologist of this or any other era," known to Egyptians as the Father of Curses and to his wife as Emerson Emerson, Walter—Radcliffe's brother, a specialist in the languages of ancient Egypt Emerson, Walter Peabody—son of Amelia and Emerson, called Ramses by his friends and an afreet (demon) by almost everybody else

CHARACTERS APPEARING OR REFERRED TO

Forth, Nefret—ward of Amelia and Emerson, granddaughter of the late Lord Blacktower

Layla—Abd el Hamed's third and most interesting wife

Mahmud—steward of the Emersons' dahabeeyah

Marmaduke, Gertrude—hired by the Emersons to tutor their children

Maspero, Gaston—reappointed in 1899 to his former position as Director of Antiquities

Murch, Chauncey—American missionary and dealer in antiquities in Luxor

Newberry, Percy—English Egyptologist

O'Connell, Kevin—star reporter of

The Daily Yell

Petrie, William Flinders—Emerson's chief rival as the founder of scientific archaeology

Quibell, J.F.—newly appointed Inspector of Antiquities for Lower Egypt

Riccetti, Giovanni—formerly in control of the illegal antiquities trade in Luxor, he intends to regain that position by any means necessary

Sethos, aka the Master Criminal—formerly in control of the illegal antiquities network in Egypt, the chief adversary of Amelia and Emerson (and Ramses)

Shelmadine, Leopold Abdullah, aka Mr. Saleh—is he the reincarnation of the High Priest Heriamon or a member of a gang of tomb robbers? Or both?

Todros, David—Abdullah's grandson

Vandergelt, Cyrus—American millionaire excavator and enthusiastic amateur of Egyptology

Washington, Sir Edward—a younger son with a talent for archaeological photography and a questionable reputation with the ladies

Willoughby, Dr.—English physician residing in Luxor

THE HIPPOPOTAMUS POOL

INTRODUCTION

For the convenience of readers who may be encountering Mrs. Emerson's journals for the first time, we have obtained permission to reprint this excerpt from

The National Autobiographical Dictionary,

45th edition.

The date of my birth is irrelevant. I did not truly

exist

until 1884, when I was in my late twenties.

1

It was in that year that I set out for Egypt with a young lady companion, Evelyn Forbes, and found the three things that were to give meaning and purpose to my life: crime, Egyptology and Radcliffe Emerson!

Emerson (who was beginning that remarkable career in archaeology which is described elsewhere in this dictionary) and his brother Walter were digging at the remote site of Amarna in Middle Egypt. Shortly after Evelyn and I joined them, the work was interrupted by a series of extraordinary events featuring what appeared to be an animated mummy. The unmasking of the villain who had inspired this apparition did not interfere unduly with a successful season of excavation.

2

My marriage to Emerson took place soon thereafter, as did the union of Evelyn to Emerson's brother. The birth of our only child, Walter Peabody Emerson, familiarly known as Ramses, necessitated a brief hiatus in our annual expeditions to Egypt. It was not until the autumn of 1889 that an appeal from the widow of Sir Henry Baskerville, whose death under mysterious circumstances had interrupted his excavation of a royal tomb at Thebes, took us back (with what delight the Reader may imagine) to Egypt. We were of course able to finish Sir Henry's work and solve the mystery of his death.

3

INTRODUCTION

We had left our son with his aunt and uncle in England that season, since his extreme youth (and certain of his habits) would have imperiled him (and everyone around him). However, he had from an early age demonstrated a keen aptitude for Egyptology, so (at the insistence of his doting father) he accompanied us to Egypt the following year. We had hoped to work at the great pyramid field of Dahshur that season, but the spite and jealousy

4

of the then Director of Antiquities relegated to us the nearby site of Mazghunah—probably the dullest and least important archaeological site in Egypt. Fortunately our work was enlivened by our first encounter with the enigmatic genius of crime known as Sethos, or, as I preferred to call him, the Master Criminal.

The details of this amazing man's career are shrouded in mystery, but it must have begun in the late 1880s, in the Luxor area. A few years later he had disposed of all rivals and ruled supreme over the illegal antiquities trade. All the objects looted from tombs and temples by unauthorized diggers, Egyptian and European, passed through his hands. Superior intelligence, a poetic imagination, utter ruthlessness, and an incomparable talent for disguise contributed to his success; only his most trusted lieutenants were aware of his true identity.

We were able that year to foil Sethos's attempt to rob the princesses' tombs at Dahshur and to escape his attempts on our lives.

5

He got away from us, though, and we found him on our trail again the following season. However, certain developments of a private nature (which are not within the scope of this article) gave us reason to believe we had seen the last of him.

6

In the autumn of 1897 we set out for the Sudan, which was being reconquered by British-led Egyptian troops after a long period of occupation by the Dervishes. We had planned to excavate in the ruins of the ancient Cushite capital of Napata, but a message from Willy Forth, an old friend of Emerson's who had been missing for over ten years, sent us out into the wastes of the Western Desert in search of him and his family. The details of that astonishing adventure (perhaps the most remarkable of our lives) have been recorded elsewhere

7

; it resulted in the rescue of Forth's daughter Nefret from the remote oasis where she had dwelt since her birth.

The winter of 1898-99 saw Emerson and me again at the site of Amarna. We had left Ramses and Nefret (now our ward) in England, and I looked forward to reliving the fond memories of my first meeting with my admirable spouse. The startling events that interrupted our excavations that year involve private personal matters that are inappropriate in an official biography;

8

suffice it to say that we encountered for the third time our great and terrible adversary, the Master Criminal, and several of his henchmen, as well as a mysterious female known to us only as Bertha. The thrilling denouement of this adventure saw Sethos felled by an assassin's bullet, the dispatch of the assassin by Emerson and the disappearance of Bertha and the henchmen....

I have often been asked to account for the frequency of our encounters with criminals of various varieties, but in my considered opinion it resulted inevitably from two causes: first, the uncontrolled state of excavation during the period in question, and second, the character of my husband. From the first, and at first almost single-handedly, Emerson fought tomb robbers, inept inspectors of antiquities and unprincipled collectors in his crusade to preserve the historic treasures of Egypt. Needless to say, I was ever at his side in the pursuit of knowledge and of villains.

1. Sic? This is not consistent with other sources. However, the editors were of the opinion that it would be discourteous to question a lady's word.

2. Crocodile on the Sandbank

3.

Curse of the Pharaohs

4. Mrs. Emerson refused to alter this statement, despite the editors' objections to its prejudicial nature.

5.

The Mummy Case

6. Mrs. Emerson's reticence on this subject is difficult to understand, since she has described these events in the fifth volume of her Memoirs,

Lion in the Valley.

1. The Last Camel Died at Noon

8. For the details of these private personal matters, cf.

The Snake, the Crocodile and the Dog

CHAPTER ONE

The Trouble with Unknown Enemies Is That They Are So Difficult to Identity

Through the open windows of the ballroom the soft night breeze of Egypt cooled the flushed faces of the dancers. Silk and satin glowed; jewels sparkled; gold braid glittered; the strains of sweet music filled the air. The New Year's Eve Ball at Shepheard's Hotel was always an outstanding event in Cairo's social season, but the dying of this December day marked an ending of greater than usual import. In little more than an hour the chimes would herald the start of a new century: January the first, nineteen hundred.

Having just completed a vigorous schottische in the company of Captain Carter, I sought a quiet corner behind a potted palm and gave myself up to speculation of the sort in which any serious-minded individual would engage on such an occasion. What would the next one hundred years bring to a world that yet suffered all the ancient ills of mankind—poverty, ignorance, war, the oppression of the female sex? Optimist though I am, and blessed with an excellent imagination (excessively blessed, according to my husband), I could not suppose a single century would see those problems solved. I was confident, however, that my gender would finally achieve the justice so long denied it, and that I myself would live to see that glorious day. Careers for women! Votes for women! Women solicitors and women surgeons! Women judges, legislators, leaders of enlightened nations in which females stood shoulder-to-shoulder and back-to-back with men!

I felt I could claim some small credit for the advances I confidently expected to see. I myself had broken one barrier: as the first of my sex to work as a field archaeologist in Egypt, I had proved that a "mere" woman could endure the same dangers and discomforts, and meet the same professional standards, as a man. Candor as well as affection compels me to admit that I could never have done it without the wholehearted support of a remarkable individual—Radcliffe Emerson, the most preeminent Egyptologist of this or any century, and my devoted spouse.

Though the room was filled with people, my eyes were drawn to him as by a magnet. Emerson would stand out in any group. His splendid height and athletic form, his chiseled features and bright blue eyes, the dark hair that frames his intellectual brow—but I could go on for several pages describing Emerson's exceptional physical and mental characteristics. Humbly I acknowledged the blessings of heaven. What had I done to deserve the affection of such a man?

Quite a lot, in fact. I would be the first to admit that my physical characteristics are not particularly prepossessing (though Emerson has, in private, remarked favorably on certain of them). Coarse black hair and steely gray eyes, a bearing more noted for dignity than grace, a stature of indeterminate size—these are not the characteristics that win a man's heart. Yet I had won the heart of Radcliffe Emerson, not once but twice; I had stood at his side, yes, and fought at his side, during the remarkable adventures that had so often interrupted our professional activities. I had rescued him from danger, nursed him through illness and injury, given him a son . . .

And raised that son to his present age of twelve and a half years. (With Ramses one counted by months, if not days.) Though I have encountered mad dogs, Master Criminals, and murderers of both sexes, I consider the raising of Ramses my most remarkable achievement. When I recall the things Ramses has done, and the things other people have (often justifiably) tried to do to Ramses, I feel a trifle faint.

It was with Ramses and his adopted sister Nefret that Emerson stood chatting now. The girl's golden-red hair and fair face were in striking contrast to my son's Arabic coloring and saturnine features, but I was startled to note that he was now as tall as she. I had not realized how much he had grown over the past summer.

Ramses was talking. He usually is. I wondered what he could be saying to bring such a formidable scowl to Emerson's face, and hoped he was not lecturing his father on Egyptology. Though tediously average in other ways, Ramses was something of a linguistic genius, and he had pursued the study of the Egyptian language since infancy. Emerson feels a natural paternal pride in his son's abilities, but he does not like to have them shoved down his throat.

I was about to rise and go to them when the music began again and Emerson, scowling even more horribly, waved the two young people away. As soon as she turned, Nefret was approached by several young gentlemen, but Ramses took her arm and led—or, to be more accurate, dragged—her onto the floor. The frustrated suitors dispersed, looking sheepish, except for one—a tall, slightly built individual with fair hair, who remained motionless, following the girl's movements with a cool appraising stare and a raised eyebrow.

Though Ramses's manners left something to be desired, I could not but approve his action. The girl's lovely face and form attracted men as a rose attracts bees, but she was too young for admirers—and far too young for the admiration of the fair-haired gentleman. I had not met him but I had heard of him. The good ladies of Cairo's European society had had a great deal to say about Sir Edward Washington. He came of a respectable family from Northamptonshire, but he was a younger son, without prospects, and with a devastating effect on susceptible young women. (Not to mention susceptible older women.)

The seductive strains of a Strauss waltz filled the room and I looked up with a smile at Count Stradivarius, who was approaching me with the obvious intention of asking me to dance. He was a bald, portly little man, not much taller than I, but I love to waltz, and I was about to take the hand he had extended when the count was obliterated—removed, replaced—by another.

"Will you do me the honor, Peabody?" said Emerson.

It had to be Emerson—no one else employs my maiden name as a term of intimate affection—but for an instant I thought I must be asleep and dreaming. Emerson did not dance. Emerson had often expressed himself, with the emphasis that marks his conversation, on the absurdity of dancing.

How strange he looked! Under his tan lurked a corpselike pallor. The sapphire-blue eyes were dull, the well-cut lips tightly closed, the thick black hair wildly disheveled, the broad shoulders braced as if against a blow. He looked ... he looked terrified. Emerson, who fears nothing on earth, afraid?

I stared, mesmerized, into his eyes, and saw a spark illumine their depths. I knew that spark. It was inspired by temper—Emerson's famous temper, which has won him the name of Father of Curses from his admiring Egyptian workmen. The color rushed back into his face; the cleft in his prominent chin quivered ominously.

"Speak up, Peabody," he snarled. "Don't sit there gaping. Will you honor me, curse it?"

I believe I am not lacking in courage, but it required all the courage I possessed to accede. I did not suppose Emerson had the vaguest idea how to waltz. It would be quite like him to assume that if he took a notion to do a thing he could do it, without the need of instruction or practice. But the pallor of his manly countenance assured me that the idea terrified him even more than it did me, and affection rose triumphant over concern for my toes and my fragile evening slippers. I placed my hand in the broad, calloused palm that had been offered (he had forgot his gloves, but this was certainly not the time to remind him of that little error).

"Thank you, my dear Emerson."

"Oh," said Emerson. "You will?"

"Yes, my dear."

Emerson took a deep breath, squared his shoulders, and seized me.

The first few moments were exceedingly painful, particularly to my feet and my ribs. I am proud to say that no cry escaped my lips and that no sign of anguish marred the serenity of my smile. After a while Emerson's desperate grip relaxed. "Hmmm," he said. "Not so bad, eh, Peabody?"

I took the first deep breath I had enjoyed since he took hold of me and realized that my martyrdom had been rewarded. For so large a man, Emerson can move with catlike grace when he chooses; encouraged by my apparent enjoyment, he had begun to enjoy himself too, and he had fallen into the rhythm of the music.

"Not bad at all," Emerson repeated, grinning. "They told me I would like it once I got the hang of it."

"They?"

"Ramses and Nefret. They were taking lessons this past summer, you know; they taught me. I made them promise not to tell you. It was to be a surprise for you, my dear. I know how much you like this sort of thing. I must say it is a good deal more enjoyable than I had expected. I suppose it is you who ... Peabody? Are you crying? Curse it, did I tread on your toes?"

"No, my dear." In shocking defiance of custom I clung closer to him, blotting my tears on his shoulder. "I weep because I am so moved. To think that you would make such a sacrifice for me—"

"A small enough return, my darling Peabody, for the sacrifices you have made and the dangers you have faced for me." The words were muffled, for his cheek rested on the top of my head and his lips were pressed to my temple.

A belated sense of decorum returned. I strove to remove myself a short distance. "People are staring, Emerson. You are holding me too close."

"No, I am not," said Emerson.

"No," I said, yielding shamelessly to his embrace. "You aren't."

Emerson, having "got the hang of it," would allow no one else to waltz with me. I declined all other partners, not only because I knew it would please him but because I required the intervals between waltzes to catch my breath. Emerson waltzed as he did everything else, with enormous energy, and between the tightness of his grasp and the vigor of his movements, which had, on more than one occasion, literally lifted me off my feet, it took me some time to recover.

The intervals gave me the opportunity to observe the other guests. The study of human nature in all its manifestations is one no person of intelligence should ignore—and what better place to observe it than in a setting such as this?

The styles of that year were very pretty, I thought, without the exaggerated outlines that had in the past distorted (and would, alas, soon again distort) the female form. Skirts fell gracefully from the waist, sans hoops or bustles; bodices were modestly draped. Black was a popular shade with older ladies, but how rich was the shimmer of black satin, how cobweb-fine the sable lace at throat and elbow! The sparkle of gems and of jet, the pale glimmer of pearls adorned the fabric and the white throats of the wearers. What a pity, I thought, that men allowed themselves to be limited by the meaningless vagaries of fashion! In most cultures, from the ancient Egyptian until comparatively modern times, the male swanked as brilliantly as the female, and presumably took as much pleasure as she in the acquisition of jewels and embroidered and lace-trimmed garments.

The only exceptions to masculine drabness of attire were the brilliant uniforms of the Egyptian Army officers. In fact, none of these gentlemen were Egyptians. Like all other aspects of the government, the army was under British control and officered by Englishmen or Europeans. The uniforms denoting members of our own military forces were plainer. There were a good many of them present that night, and in my imagination I seemed to see a faint shadow darkening those fresh young faces, so bravely mustachioed and flushed with laughter. They would soon be on their way to South Africa, where battle raged. Some would never return.

With a sigh and a murmured prayer (all a mere woman can offer in a world where men determine the fate of the young and helpless) I returned to my study of human nature. Those who were not dancing sat or stood around the room watching the intricacies of the cotillion, or chatting with one another. A good many were acquaintances of mine; I was interested to observe that Mrs. Arbuthnot had gained another several stone and that Mr. Arbuthnot had got a young lady whom I did not recognize backed into a corner. I could not see what he was doing, but the young lady's expression suggested he was up to his old tricks. Miss Marmaduke (of whom more hereafter) had no partner. Perched on the edge of her chair, her face set in an anxious smile, she looked like a bedraggled black crow. Next to her, ignoring her with cool discourtesy, was Mrs. Everly, wife of the Interior Minister. From the animation that wreathed her face as she carried on a conversation across Miss Marmaduke with the latter's neighbor, I deduced that the lady, swathed in black veiling, was a Person of Importance. Was she a recent widow? No lesser loss could dictate such heavy mourning; but if that were the case, what was she doing at a social function such as this? Perhaps, I mused, her loss was not recent. Perhaps, like a certain regal widow, she had determined never to leave off the visible signs of bereavement.

(I reproduce the preceding paragraphs in order to demonstrate to the Reader how much can be offered to the serious student of human nature even in so frivolous a social setting as that one.)

It would be my last social event for some time. In a few more days we would leave the comforts of Cairo's finest hotel for ...