The History of Florida (2 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

North America and was at least as wide as the distance from Orlando to

proof

New York City.

These early hunter-gatherers are cal ed Paleoindians, and they entered

Florida around 10,000 B.C., about the same time that they moved into other

parts of what is now the United States. Evidently their nonsedentary lifestyle

and a new world filled with plant and animal foods never encountered pre-

viously by humans enabled—perhaps encouraged—them to colonize the

Americas quickly. Campsites of the Paleoindians are found across North

America from Alaska to south Florida.

Some archaeologists argue that the Paleoindian migration was preceded

by even earlier movements of people from Asia across the Siberia-Alaska

land bridge into the Americas. But as yet the evidence for such a pre-Pa-

leoindian presence in North America is tenuous. Certainly in Florida, the

Paleoindians were the first human residents.

At the time of the Florida Paleoindians, the same lowered seas that cre-

ated a transcontinental bridge across the Bering Strait gave Florida a total

landmass about twice what it is today. The Gulf of Mexico shoreline, for

instance, was more than 100 miles west of its present location. During the

Paleoindian period, Florida also was much drier than it is today. Many of

our present rivers, springs, and lakes were not here, and even groundwater

· 3 ·

4 · Jerald T. Milanich

levels were significantly lower. Plants that survived were those that could

grow in the dry, cool conditions. Scrub vegetation, open grassy prairies, and

savannahs were common.

Sources of surface water, so important to Paleoindians and to the animals

they hunted for food, were limited. The Paleoindians sought water in deep

springs, like Little Salt Spring in Sarasota County, or at watering holes or

shallow lakes or prairies where limestone strata near the surface provided

catchment basins. Such limestone deposits are found from the Hil sborough

River drainage north through peninsular Florida into the Panhandle. Paleo-

indians hunted, butchered, and consumed animals at these watering holes,

leaving behind their refuse, artifacts that can be studied and interpreted by

modern archaeologists.

Today, with higher water levels, many of these catchment basins are flow-

ing rivers, like the Ichetucknee, Wacissa, Aucil a, and Chipola. Paleoindian

camps with bone and stone weapons and tools, including distinctive lan-

ceolate stone spear points, are found in deposits at the bottoms of these

rivers, as well as at land sites nearby. With the stone tools are found bones

of the animals the Paleoindians hunted, some exhibiting butchering marks.

A number of the animal species hunted by Paleoindians became extinct

shortly after the end of the Pleistocene epoch, perhaps in part because of

proof

human predation. They include mastodon, mammoth, horse, camel, bison,

and giant land tortoise. Other of the animals that provided meat for the

Paleoindian diet—deer, rabbits, raccoons, and many more—continue to in-

habit Florida today.

After about 9000 B.C., as glaciers melted and sea levels rose, Florida’s

climate general y became wetter than it had been, providing more water

sources around which the Paleoindians could camp. But as the sea rose,

coastal areas were flooded and the Florida landmass was reduced. Less land

and larger human populations may have influenced the later Paleoindians

to follow a less nomadic way of life. They moved between water sources less

frequently, and their camps were occupied for longer periods of time. Ar-

chaeological sites corresponding to these larger late Paleoindian camps have

been found in the Hil sborough River drainage near Tampa, around Paynes

Prairie south of Gainesville, near Silver Springs, and at other locations in

northern Florida.

Paleoindian sites, relatively common in the northern half of the state

in the region of surface limestone strata, also occur in smaller numbers in

southern Florida. Paleoindian artifacts have been found as far south as Dade

County.

Original Inhabitants · 5

proof

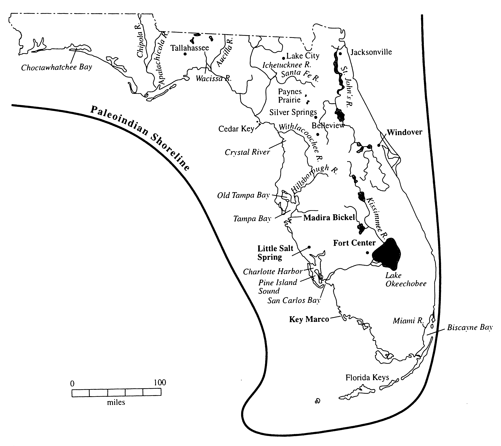

Archaeological sites (

in bold

) and other Florida locations mentioned in chapter 1.

Over time the tool kits of the Paleoindians changed as people altered

their lifeways to adjust to the new environmental conditions that con-

fronted them. They began to use a wider variety of stone tools, and many of

the stone points original y used to hunt the large Pleistocene animals were

no longer made. These changes were sufficient by 7500 B.C. for archaeolo-

gists to delineate a new culture, the early Archaic.

The environment of the early Archaic peoples was stil drier than our

modern climate, but it was wetter than it had been in earlier times. Early

Archaic peoples continued to live next to wetlands and water sources and

to hunt and gather wild foods.

One remarkable early Archaic period site is the Windover Pond site in

Brevard County, which contains peat deposits in which early Archaic people

interred their dead. Careful excavations by Glen Doran and David Dickel

of Florida State University revealed that during the period between 6000

6 · Jerald T. Milanich

and 5000 B.C., human burials were placed in the peat in the bottom of the

shallow pond. The peat helped to preserve an array of normal y perishable

artifacts and human tissues, including brains, from which scientists have

recovered and studied genetic material.

Artifacts recovered by the excavation team included shark teeth and dog

or wolf teeth which had been attached with pitch to wooden handles for use

as tools. Other tools were made from deer bone and antler, from manatee

and either panther or bobcat bone, and from bird bone. Bone pins, barbed

points, and awls were found preserved in the peat, along with throwing stick

weights made from deer antler. The weights were used with a handheld shaft

to help launch spears; the earlier Paleoindians probably also used throwing

sticks.

Animal bones found in the pond, presumably from animals eaten by the

people who lived there, were from otter, rat, squirrel, rabbit, opossum, duck

and wading birds, alligator, turtle, snake, frog, and fish. Remains of plants,

including prickly pear and a wild gourd fashioned into a dipper, were also

preserved.

A wel -developed and sophisticated array of cordage and fiber fabrics and

matting lay in the Windover Pond peat. Fibers taken from Sable palms, saw

palmettos, and other plants were used in twining and weaving. The early

proof

Archaic people of Florida, like the people that preceded them and those that

would fol ow, had an assemblage of material items—tools, woven fabrics,

and the like—well suited to life in Florida.

After 5000 B.C., the climate of Florida began to ameliorate, becoming

more like modern conditions, which were reached by about 3000 B.C. The

time between 5000 and 3000 B.C. is known as the middle Archaic period.

Middle Archaic sites are found in a variety of settings, some very different

from those of the Paleoindians and early Archaic periods, including, for the

first time, some along the St. Johns River and the Atlantic coastal strand.

Middle Archaic peoples also were living in the Hil sborough River drainage

northeast of Tampa Bay, along the southwest Florida coast, and in a few

south Florida locales. And middle Archaic sites are found in large numbers

in interior northern Florida. The presence of a larger number of surface wa-

ter sites than had been available in earlier times provided many more locales

for people to inhabit.

It is clear that during the middle Archaic period Florida natives took ad-

vantage of the increased number of hospitable areas. Populations increased

significantly. The people practiced a more settled way of life and utilized a

larger variety of specialized tools than their ancestors had done.

Original Inhabitants · 7

By 3000 B.C., the onset of the late Archaic period, essential y modern

environmental conditions were reached in Florida, and expanding popula-

tions occupied almost every part of the state. Wetland locales were heav-

ily settled. Numerous late Archaic sites have been found in coastal regions

in northwest, southwest, and northeast Florida and in the St. Johns River

drainage. Such sites, representing the remains of vil ages, are characterized

by extensive deposits of mol usks—snails and mussels at freshwater loca-

tions and oysters along the coasts—which represent the remains of thou-

sands of precolumbian meals. At both marine and freshwater settlements,

fish and shellfish were dietary staples, as they were for many generations of

later native Floridians.

Late Archaic groups probably lived along most if not al of Florida’s

coasts, but many of their sites have been inundated by the sea rise that con-

tinued throughout the Archaic period as Pleistocene glaciers melted. This

is certainly true around Tampa Bay, where dredging has revealed extensive

shell middens that today are underwater. It is also likely that Paleoindian

and early and middle Archaic sites have been covered by the rising sea.

Slightly before 2000 B.C., the late Archaic vil agers learned to make fired

clay pottery, tempering it with Spanish moss or palmetto fibers. Sites with

fiber-tempered pottery, some associated with massive shel middens, are

proof

distributed throughout the entire state down to the Florida Keys.

By the end of the late Archaic period at 500 B.C., many new types of

fired clay pottery were being made by regional groups. Because different

groups made their ceramic vessels in specific shapes and decorated them

with distinctive designs, archaeologists can use pottery as a tool to define

and study specific cultures. Often those cultures are named for the modern

geographical landmarks where their remains were first recognized. In some

instances we can trace, albeit incompletely, the evolution of these regional

cultures from 500 B.C. into the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when

European powers sought to colonize Florida. We can correlate the preco-

lumbian archaeological cultures with native American groups described in

colonial-period European documents.

Each regional culture with its distinctive style of pottery tended to live

within one major environmental or physiographic zone. Each developed

an economic base and other cultural practices that were well suited to that

particular region and its various habitats and resources.

Like their Archaic and Paleoindian ancestors, the people associated with

these post–500 B.C. regional cultures made a variety of stone tools as wel .

Today examples of those tools are found throughout Florida, although they

8 · Jerald T. Milanich

are more numerous in regions where chert—a flintlike stone—was mined

from limestone deposits and fashioned into spear and arrow points, knives,

scrapers, and a variety of other tools.

East Florida—including the St. Johns River drainage from Brevard

County north to Jacksonville, the adjacent Atlantic coastal region, and the

many lakes of central Florida—was the region of the St. Johns culture. Like

the late Archaic groups that preceded them, the St. Johns people made ex-

tensive use of fish and shellfish and other wild foods. They hunted and col-

lected the foods that could be found in the natural environment where they

lived.

By 100 B.C. or shortly after, the St. Johns people were constructing sand

burial mounds in which to inter their dead. Each vil age had a leader or

leaders who helped coordinate activities, such as communal ceremonies.

Vil agers most likely were organized into a number of lineages or other kin-

based groups, each of which probably had a name and distinctive parapher-

nalia or other symbols of membership.

When a vil age grew too large for its residents to be supported easily by

local economic resources, one or more lineages broke away, establishing a

new vil age nearby. Traditions and shared kinship and origins served to tie

old and new vil ages together. Such a social system probably was present in