The History of Florida (39 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

Southeast.

Other Africans remained with de Soto’s force for the duration. Ber-

naldo, a free caulker from Vizcaya and formerly the slave of one of de Soto’s

captains, survived the many bloody Indian battles, severe hunger, kil ing

marches, and final y a voyage down the Mississippi River in hastily con-

structed boats. After an epic voyage of more than four years, during which

the expeditionaries traversed 600 miles and ten of the present-day United

States, Bernaldo was among those who limped back to Mexico City dressed

only in animal skins.

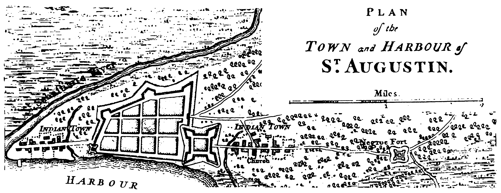

Several more attempts failed before Pedro Menéndez de Avilés final y

established the first permanent settlement at St. Augustine in 1565. By that

time persons of African descent had already taken up residence in the pen-

insula. When Menéndez first explored his claim, he found a shipwrecked

mulatto named Luis living among the fiercely resistant Ais nation to the

south. Luis’s knowledge of the Ais language had saved other shipwreck vic-

tims whose freedom Menéndez negotiated, among them an unnamed black

woman. Luis became a translator for Menéndez and returned to live among

the Spaniards, but other “captives” chose to stay with the Indians. Menéndez

proof

complained later that slaves from St. Augustine ran to and intermarried

with the Ais. The possibility of an alternative life among the Indians would

temper race relations in Florida well into the nineteenth century.

Although a royal charter permitted Menéndez to import 500 African

slaves to do the difficult labor required in settling a new colony, he never

filled that contract, and probably fewer than fifty slaves may have accom-

panied the first settlers. The loss of those slaves who ran to the Ais was

significant. White manpower was in short supply in Florida, as it was in

other areas of the Caribbean, and Spaniards considered Indians to be too

weak, lazy, and transient to be a dependable labor force. Moreover, the na-

tive populations were extremely vulnerable to European diseases which had

already ravaged their counterparts in the Antilles. Thus, the slaves who re-

mained performed many critical functions in Spanish Florida, first at St.

Augustine and later at Santa Elena, Spain’s northernmost settlement, in

present-day South Carolina. Slaves logged and sawed the timber for fortifi-

cations and ships, built structures, and cleared and planted the fields, “with

no other expense but their oil and salt.”1 The Crown considered black labor

indispensable to the maintenance of Florida, noting that the entire govern-

ment subsidy would not suffice if wages had to be paid for their labor. By

Free and Enslaved · 183

the seventeenth century, the government was depending on royal slaves to

quarry coquina from Anastasia Island, make lime, load and unload govern-

ment ships, and row government galleys. Private owners of slaves employed

them in domestic occupations, as cattlemen and overseers on Florida’s vast

cattle ranches, and in a myriad of plantation jobs.

In times of crisis slaves and free Africans were also expected to help de-

fend the colony and provide military reserves for the badly understaffed

military garrison. After the late sixteenth century, the “Spanish Lake” was

infested with corsairs from England, France, and Hol and who raided Span-

ish shipping and settlements with seeming impunity. Florida’s long exposed

coastline made it particularly vulnerable to attack. By 1683 free blacks in St.

Augustine had formed themselves into a formal militia unit and were com-

manded by officers of their own election. Similar units served in Hispaniola,

Cuba, México, Puerto Rico, Cartagena, and throughout Central America.

The men who formed the black militias were usual y free black artisans

or skil ed workers. They were Catholics who lived as Spaniards and were

integrated into their communities through powerful social institutions such

as godparentage and patron/client networks. Leading useful and orderly

lives, they mirrored the early free African communities of Spain and en-

joyed the protections promised by Spanish law and custom. Military service

proof

was an important way for free blacks to prove themselves to their com-

munity and also to advance themselves through occasional opportunities

for plunder. Moreover, through the militias, free blacks acquired titles and

status and eventual y full military privileges. It is possible that the militia

units also functioned to reinforce relationships within the African com-

munity, as “natural” leaders rose to command and assumed responsibility

for their men. Parish registers from St. Augustine show that militia families

commonly intermarried and served as godparents and marriage sponsors

for one another. Church records also suggest that the double connection of

family and military corporatism may have worked to move some men out

of slavery. Although their slave past was certainly not forgotten, it was in a

sense excused by appropriate behavior, valuable services, and the sponsor-

ship of Africans of whom the community already approved.

Michael Mul in’s recent study of slavery in the contemporary British

Caribbean demonstrates how geographic context and the organization of

labor shaped the institution of slavery. In Florida slavery exhibited a num-

ber of the features that Mullin contends mitigated its oppressive nature: it

was general y organized by the task system, and slaves had free time to en-

gage in their own social and economic activities; slaves were able to utilize

184 · Jane Landers

the resources of both frontier and coast to their advantage; the trade in

slaves was never massive; and the paternal model of plantation management

prevailed, even on Florida’s largest ranches and plantations. Moreover, the

geopolitical pressures exerted by Spain’s circum-Caribbean rivals meant ad-

ditional leverage for slaves and more Spanish dependence upon free people

of color.

In 1670 English planters from Barbados challenged Spain’s claim to ex-

clusive control of the Atlantic seaboard by establishing Charles Town. St.

Augustine lacked sufficient force to mount a major attack against the usurp-

ers, but Spanish governors initiated a campaign of harassment against the

English colony that included slave raids by the Spaniards and their black

and Indian allies. These contacts may have pointed the way to St. Augus-

tine and suggested to English-owned black slaves the possibility of a refuge

among the enemy, for in 1687, after a dramatic escape by canoe, eight men,

two women, and a nursing child appeared in Florida. The fugitive slaves

requested religious sanctuary in St. Augustine, and, despite an early am-

biguity about their legal condition, only in one known example were the

runaways returned to their English masters. The rest were sheltered in St.

Augustine, instructed and baptized in the Catholic faith, married, and em-

ployed, ostensibly for wages. Royal policy regarding the fugitives was final y

proof

set in 1693 when Charles II granted the newcomers to Florida freedom on

the basis of religious conversion, “the men as well as the women . . . so that

by their example and by my liberality others will do the same.”2 In gratitude

the freedmen vowed to shed their “last drop of blood in defense of the Great

Crown of Spain and the Holy Faith, and to be the most cruel enemies of

the English.”3 The runaways had considered their options and made their

choices.

During the next decades more fugitives from Carolina flowed into St.

Augustine, and in 1738 the Spanish governor established the freedmen and

-women in the town of Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, about two

miles north of St. Augustine. Florida’s governor recognized the group’s

spokesman and the captain of their newly formed militia, Francisco Mené-

ndez, as the “chief” of Mose and referred to the others living at the vil age as

his “subjects.” The residents of Mose established complex family and fictive

kin networks over several generations and successful y incorporated into

the founding group incoming fugitives, Indians from nearby vil ages, and

slaves from St. Augustine. Community and familial ties were further rein-

forced by a tradition of militia service at Mose.

proof

Many former slaves and free African Americans served in Spanish militias in Florida

and throughout the circum-Caribbean in the eighteenth century. The soldiers depict-

ed here were posted at Havana, Cuba, and Veracruz, México.

186 · Jane Landers

However, despite the best efforts of Menéndez and his men, the first town

of Mose was destroyed when General James Oglethorpe commanded a joint

naval and land assault against St. Augustine in 1740. Mose’s inhabitants took

up residence in St. Augustine until Governor Fulgencio García de Solís at-

tempted to relocate the freedmen to Mose in 1752. The former residents

feared further attacks and did not want to move back, but after the governor

promised to fortify the settlement better and to post soldiers at the site, the

freedmen rebuilt Mose, constructing a church and a house for the Francis-

can priest within an enclosed fort as well as twenty-two shelters outside the

fort for their own households.

Kathleen Deagan of the Florida Museum of Natural History directed an

interdisciplinary investigation of Mose that has added to the documentary

record archaeological, or material, evidence about daily life at this unique

site. In two seasons of excavations her team uncovered the foundations and

earthen walls of the fort, parts of the palisade, sections of the moat, and

several of the interior structures. They also recovered military artifacts such

as bullets, gunflints, and buttons and domestic items such as bone buttons,

pins and thimbles, clay pipe bowls, beads, and a variety of eighteenth-cen-

tury ceramics and bottles. One valuable find was a handmade pewter St.

Christopher’s medal, which may be a reference to the Africans’ travels over

proof

water or suggest links to Havana, for which St. Christopher was the patron.

While conditions at Mose were rugged, the homesteaders were at least

free to farm their own lands, build their own homes, and live in them with

their families. A house-by-house census of Mose from 1759 identified

thirty-seven men, fifteen women, seven boys, and eight girls living at the

site. Included were members of the Mandinga, Congo, and Carabalí nations,

as well as many others, but over time the diverse ethnic-linguistic groups

formed a cohesive community that survived until 1763. Then, through the

fortunes of war, Spain lost Florida to the British, and the Spanish Crown

evacuated St. Augustine and its black and Indian allies to Cuba.

Under British rule (1763–84), black freedom in Florida became only a re-

mote possibility. Anglo planters established vast indigo, rice, sugar, and sea

island cotton plantations modeled after those in South Carolina and Geor-

gia. Historian Daniel L. Schafer has found that wealthy planters, such as

Richard Oswald and John Fraser, imported large numbers of African slaves

from Sierra Leóne for the back-breaking work involved in establishing new

plantations. Soon Africans were the most numerous element of Florida’s

population. The American Revolution accelerated that trend, for after the

Patriots took Charleston and Savannah, planters shifted whole work forces