The History of Florida (46 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

entry and exit of numerous third parties, the commission determined that

the Seminoles should be awarded a little more than $12 mil ion for lands

taken in the 1820s and 1830s at less than market value. Unfortunately, the

commission failed to specify how the money was to be divided among the

Seminole, Miccosukee, and Oklahoma Seminole Tribes. After an appeal by

proof

the Seminoles, the commission awarded the tribes $16 million in 1976 but

did not resolve the distribution problem. In 1990, twenty years after the

initial award, Congress mandated a 75/25 split of the $50 million settlement

(the 1976 award plus interest) between the Oklahoma and Florida Semi-

noles. The Florida share, amounting to some $12.3 million, was divided be-

tween the Seminole tribe (77.2 percent), the Miccosukees (18.6 percent),

and independent Seminoles, legal y recognized ful -blooded Indians who

are not tribal members (4.6 percent).

The Seminole Tribe, based at the Hol ywood Reservation, is governed by

an elected tribal council representing each of the reservations and, through

its corporate branch, engages in many sophisticated and complex business

ventures. The smaller Miccosukee Tribe—organized similarly to the Semi-

nole Tribe—conducts tribal business from its headquarters on the Tamiami

Trail reservation. In recent years, both tribes have made bold forays into the

world of high-stakes gaming.

Too frequently the Seminoles and Miccosukees have been defined in the

public mind by popular media reports on legal battles with state or federal

authorities over gaming, land- and water-use rights, and the civil rights of

citizens of Indian nations. Federal law recognizes the sovereign status of

218 · Brent R. Weisman

designated Indian tribes and nations, but sovereignty as both a political

and civil concept is not well understood at the state and local governmental

levels. The Seminoles, Miccosukees, and many other Indian nations have

used their sovereign status to build economic self-sufficiency through the

sales of tax-free cigarettes and bingo revenues. The Seminole Tribe in par-

ticular parlayed these revenues into surprising political clout and bold fi-

nancial investments. In 2006, the Seminole Tribe purchased the Hard Rock

Corporation. The $965 mil ion deal included 124 Hard Rock Cafes, four

Hard Rock Hotels, two Hard Rock Casinos (already doing business on res-

ervation property in Tampa and Hol ywood), and a variety of subsidiary

enterprises. Although most of the tribal revenue comes from gaming, more

conventional pursuits such as cattle ranching, particularly on the Brigh-

ton reservation (where it has become a multimillion-dol ar enterprise), and

growing lemons, grapefruits, and oranges have added to the diversified eco-

nomic portfolio. In 2009, the Seminole Tribe negotiated a compact with the

State of Florida for initial payments of $150 mil ion per year to state cof-

fers in exchange for exclusive rights to offer blackjack and slot machines at

tribal casinos. Negotiations such as these often polarize public opinion and

encourage misconceptions about the integrity of Seminole culture. To the

Seminoles, however, there are no misconceptions. The economic success of

proof

their gaming enterprise underwrites the survival of their cultural identity.

They can continue to be Seminoles because they have found a viable way to

maintain their independence. They take pride in their self-designation as

the “Unconquered People,” an homage to their survival through the era of

the Seminole wars.

Although modern ranch-style houses with manicured lawns have largely

replaced the standard reservation-style concrete block house, which largely

replaced the traditional chickee, and Christianity has been long since ac-

cepted, much remains of traditional Seminole culture. In early summer,

dance grounds are prepared for the annual Green Corn Dance, directed

by a tribal medicine man, much as was done in the nineteenth century and

before. Here families come and children learn the traditional ways. Cultural

education takes place in the reservation schools and through programming

offered through the tribal Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki museum. The simple wood-

framed “Red Barn” on the Brighton Reservation, built to stable Seminole

horses in the early years of the cattle industry, was listed on the National

Register of Historic Places in 2008 and wil become another educational

point of pride for Seminole youth. Combined Seminole and Miccosukee

population numbers now approximate their pre–Second Seminole War

Florida’s Seminole and Miccosukee Peoples · 219

total. Despite unprecedented levels of wealth that would have been beyond

the comprehension of earlier generations, much uncertainty remains and

new generations must be prepared for the future. If history can serve as a

guide, the Seminoles will find a way to endure.

Bibliography

Blackard, David M.

Patchwork

and

Palmettos:

Seminole

Miccosukee

Folk

Art

since

1820

.

Fort Lauderdale: Fort Lauderdale Historical Society, 1990.

Cattelino, Jessica R.

High

Stakes:

Florida

Seminole

Gaming

and

Sovereignty

. Durham: Duke University Press, 2008.

Covington, James W.

The

Seminoles

of

Florida

. Gainesvil e: University Press of Florida,

1993.

Garbarino, Merwyn S.

Big

Cypress:

A

Changing

Seminole

Community

. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1972.

Kersey, Harry A., Jr.

An

Assumption

of

Sovereignty:

Social

and

Political

Transformation

among

the

Florida

Seminoles,

1953–1979

. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996.

MacCauley, Clay. “The Seminole Indians of Florida.” In

Fifth

Annual

Report

of

the

Bureau

of

Ethnology

, pp. 469–531. Washington, 1887.

Mahon, John K.

History

of

the

Second

Seminole

War

. Gainesvil e: University of Florida Press, 1967.

Sprague, John T.

The

Origin,

Progress,

and

Conclusion

of

the

Florida

War

. 1848. Gainesville: proof

University of Florida Press, 1964.

Sturtevant, William C., editor.

A

Seminole

Source

Book

. New York: Garland, 1987.

Weisman, Brent R.

Unconquered

People:

Florida’s

Seminole

and

Miccosukee

Indians

.

Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1999.

West, Patsy.

The

Enduring

Seminoles:

From

Al igator

Wrestling

to

Ecotourism

. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1998.

Wickman, Patricia R.

Osceola’s

Legacy

. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1991.

Wright, J. Leitch, Jr.

Creeks

and

Seminoles:

The

Destruction

and

Regeneration

of

the

Muscogulge

People

. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1987.

13

U.S. Territory and State

Daniel L. Schafer

On 17 July 1821, as the Stars and Stripes replaced the Spanish flag in the

public square outside Government House in Pensacola, America’s greatest

living military hero, General Andrew Jackson, supervised the ceremony.

Jackson, the man from Tennessee who in March 1814 led a coalition of

Americans and Indian allies in the decisive defeat of the Upper Creek at the

Battle of Horseshoe Bend that ended the Creek War, and nine months later

led the American army in a historic victory over a British army at the Battle

of New Orleans, had accepted President James Monroe’s offer to become

proof

the first American governor of Florida. Jackson had led American armies

on punishing invasions of the Spanish East and West Florida provinces in

1814 and 1818. The latter campaign, known as the First Seminole War, per-

suaded Spain to cede East and West Florida to the United States. Instead of

praise from Washington, however, Jackson’s political opponents impugned

his Florida victory as an outrageous usurpation of military power. Presiding

over the ceremonies in which Spain relinquished al claims to territories east

of the Mississippi River was for Jackson a triumphal moment.

There had been frustrating delays and vexations in the months of nego-

tiations that preceded the exchange of flags. The Adams-Onís Treaty was

signed by the principal negotiators on 22 February 1819 and approved by

the U.S. Senate within days, yet Spanish officials delayed approval until 24

October 1820. The U.S. Senate again ratified the treaty on 19 February 1821,

and President James Monroe and Secretary of State John Quincy Adams ap-

pointed Jackson governor of the new Territory of Florida on 12 March and

ordered him to proceed to Pensacola. Jackson appointed a subordinate, Lt.

Robert Butler, to manage the transition in St. Augustine. After further de-

lays, the exchange of flags final y took place on 10 July 1821 in St. Augustine

and 17 July in Pensacola.

· 220 ·

U.S. Territory and State · 221

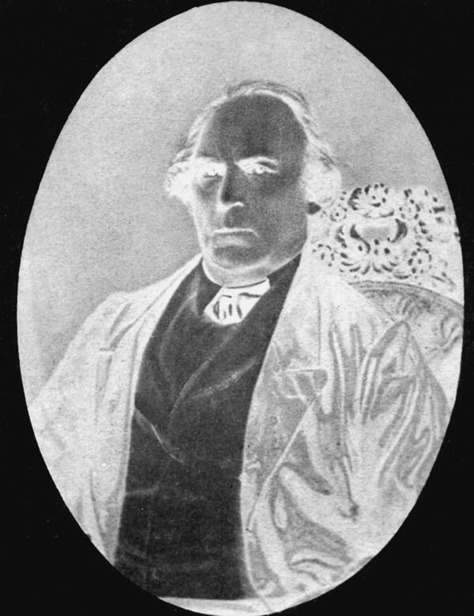

Portrait of Richard

K. Call. Courtesy of

the State Archives

of Florida,

Florida

Memory

, http://

proof floridamemory.com/

items/show/128615.

Jackson’s tenure as governor was brief and tempestuous. He resigned

his office in September and departed Pensacola in early October. Before

leaving, however, the hot-tempered Jackson ordered Spanish governor José

Cal ava jailed briefly for obstructing delivery of documents pertinent to a

lawsuit. In an attempt to justify this serious diplomatic blunder, Jackson said

he had acted to protect the rights of a free quadroon woman who had been

cheated of her inheritance, an injustice that had been perpetuated for fifteen

years. His motive, Jackson explained later, had been to prevent “men of high

standing” from “trampl[ing] on the rights of the weak.”1

The incident soon passed from public consciousness, but the new gov-

ernor’s prickly temperament continued to raise alarm bel s in Washington.

Jackson was greatly troubled when President Monroe refused to accept his

nominees for the principal posts in the Florida administration. Jackson had

expected wide powers of patronage to reward his loyal associates. Instead,

Monroe appointed the higher-ranking secretaries, judges, and attorneys.

Jackson chose officeholders for Escambia and St. Johns Counties, two vast

222 · Daniel L. Schafer

administrative units that were reminiscent of the separate provinces of

Spanish East and West Florida. He also chose the judges for the county

courts and the mayors and aldermen of St. Augustine and Pensacola.

Richard Keith Cal , who would serve with distinction in Florida for the

next four decades, was the most important of Jackson’s appointees. He had

joined a volunteer unit under Jackson’s command in 1813, and participated

in the Battle of New Orleans and both Florida campaigns. Call handled the

early negotiations with Governor Cal ava and was named to the Pensacola

Town Council. He established a thriving law practice, served on the Florida

Legislative Council in 1822 and 1823 and as territorial delegate to Congress

in 1824. He also became a brigadier general in the Florida militia, and was

twice named governor of the territory. Cal became the leader of Ameri-

can Florida’s first governing elite, known popularly as the “Nucleus.” After

Jackson’s resignation, however, it was William P. Duval, a U.S. judge at Pen-

sacola, who succeeded him. Duval was a supporter of Jackson and general y

followed his policies.

In March 1822, Congress replaced the provisional structure with a single