The History of Florida (86 page)

Read The History of Florida Online

Authors: Michael Gannon

Tags: #History, #United States, #State & Local, #Americas

The Maritime Heritage of Florida · 409

The historic coastal schooner

Governor Stone

is now a floating museum and school.

Courtesy of the Friends of the Governor Stone, Inc.

was tried and hanged at the USCG base in Ft. Lauderdale. The war against

smuggling took a new direction soon afterwards as the need to locate smug-

glers farther out at sea led to an emphasis on air reconnaissance. The first

proof

Coast Guard Air Station was commissioned in Miami in 1926, followed by

another at St. Petersburg in 1934. Thereafter, the USCG took a more active

role along Florida’s waters and beaches.

Shipping continued to provide some economic stability to Florida. With

the state’s long distances and limited roadways, coastal shipping remained

the most convenient and viable method of moving people and goods around

Florida. One of Florida’s most famous coastal steamers,

Tarpon

, ran along

the Panhandle from St. Andrews Bay (Panama City) to Pensacola and Mo-

bile, Alabama, for more than thirty years. In 1937,

Tarpon

, heavily loaded,

rounded the sea buoy at Pensacola bound for St. Andrews. Caught in a fierce

gale, the ship began taking on water. Cargo was jettisoned and the vessel

was turned toward shore to try to ground her, but

Tarpon

was still 11 miles

offshore when she sank, taking eighteen people down with her. Today, the

remains of

Tarpon

lie in 90 feet of water off Panama City and are designated

a State Underwater Archaeological Preserve.

Shipping took on renewed importance with the outbreak of the Second

World War. German submarines, or U-boats, operated in the Gulf of Mex-

ico and in the Atlantic off Florida, prompting dim-out policies in coastal

communities to help prevent ship silhouettes becoming visible against the

t

i-

.

or

w

t

Half

ve

.

w

fm.

itage

er

tmen

ist

x.c

ach

ater w

mission

reser

epar

ttp://w, h

ical P

ed on the

itime Her

ecks post

om/inde

tur

ar

wr

ida D

ces

.c

eck of the y

lor

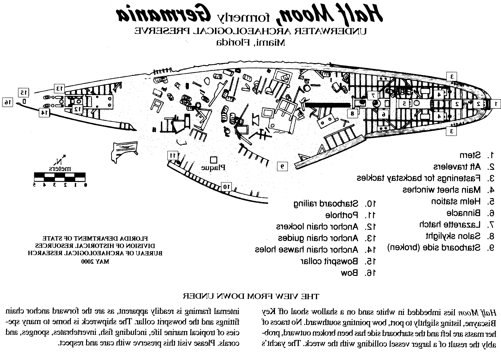

is an Under

ea

ted with perin

te, Division of H

esour

itage

on

ida M

ta

rchaeolog

The wr

Mo

A

and is f

Flor

Trail Ship

Repr

of the F

of S

cal R

flher

proof

The Maritime Heritage of Florida · 411

lighted backgrounds of cities. Nevertheless, U-boats succeeded in sinking

twenty-four U.S. and Allied freighters and tankers off Florida’s shores, most

in the first six months of 1942. In April 1942,

Gulfamerica

, carrying 90,000

barrels of fuel oil, was hit by U

-123

and exploded in sight of horrified specta-

tors at Jacksonville Beach.

Some of those casualties are now popular diving attractions.

Empire

Mica

, a British steam tanker carrying a load of oil, was torpedoed by U-

67

in June 1942 south of St. George Island in the Gulf of Mexico. Today the

shipwreck, located in 100 feet of water 45 miles offshore, is a top diving des-

tination and is especial y popular for spearfishing. Other, more mysterious,

casualties of the maritime war include the tramp steamer

Vamar

, built as the

British gunboat

Kilmarnock

, which sank under questionable circumstances

off Port St. Joe in March 1942. Loaded with a cargo of lumber and bound

for Cuba,

Vamar

sank in calm conditions and flat water, nearly blocking

the shipping channel; local people suspected foreign sabotage although no

conclusive evidence was found. Today the shipwreck is a state Underwater

Archaeological Preserve and is listed on the National Register of Historic

Places.

Naval bases at Key West, Tampa, and Valparaiso came back into action

as World War II ramped up, and naval air stations trained Navy pilots in

proof

Pensacola, Jacksonville, Key West, Miami, Ft. Lauderdale, Vero Beach, Mel-

bourne, Banana River, Daytona Beach, and DeLand. The Civil Air Patrol

and the “Mosquito Fleet” were established to protect and patrol Florida’s

coasts. Military construction and the influx of military personnel helped to

enlarge the economy and place Florida in a strong economic situation as the

state entered the postwar era.

Into the Twenty-First Century

Florida has been, and wil always be, a maritime state tied to the sea. Its

unique geography and location make ocean commerce and recreation in-

evitable components of Florida’s economy. As early as the 1960s, Florid-

ians began to react to the negative effects of shipping, fishing, tourism, and

other maritime-related activities. Pol ution and destruction of natural re-

sources led Florida’s citizens to reevaluate the uses of precious rivers, bays,

and coastal waters. Today, Florida’s prosperity and destiny still lie with the

sea as millions of tons of cargo and billions of dol ars in revenue annual y

pass through the major ports of Miami, Tampa, and Jacksonville. Offshore

exploration, both in the Gulf and the Atlantic, for petroleum resources such

412 · Del a A. Scott-Ireton and Amy M. Mitchell-Cook

as oil and natural gas is becoming more prevalent. In the future, sites may be

needed for wind farms and solar panel arrays, likely also impacting Florida’s

offshore and coastal areas.

The vacation and tourism industry also plays a part in Florida’s maritime-

focused economy. In addition to commercial cargo, Florida’s ports support

pleasure-cruising ships that host millions of vacationers each year. The Port

of Miami and nearby Port Everglades are the two top cruise ship ports in

the world. Commercial and recreational fishing supplies seafood for local

tables and for distant markets and restaurants, while sportfishing draws an-

glers from around the world. Florida also is the nation’s top scuba diving

destination, with warm, clear water, colorful fish, historic shipwrecks, and

the United States’ only tropical coral reef. John Pennekamp Coral Reef State

Park in Key Largo is the nation’s first park dedicated to undersea marine life

and includes shipwrecks as wel as natural resources. National parks and

preserves, such as Biscayne National Park near Miami, NOAA’s Florida Keys

National Marine Sanctuary, and Gulf Islands National Seashore in the Pan-

handle, preserve the natural beauty and cultural heritage of Florida’s coasts

and oceans, ensuring the state’s historical maritime heritage is preserved for

future generations. Even today, refugees seeking a better life build rafts and

small boats to make the ocean journey to Florida.

proof

Maritime Archaeology and the Underwater Cultural Heritage

With the exception of rare vessels like

Governor

Stone

still afloat, informa-

tion about Florida’s maritime heritage can only be found in historical docu-

ments and in the archaeological record. When documents are missing or

lost, archaeology is the only way we have of learning about the ships and

boats that helped build the state. Florida’s submerged heritage sites, includ-

ing shipwrecks and prehistoric remains, are protected under federal and

state law, just as historical and archaeological sites on land are protected.

Federal laws including the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 and

the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 protect heritage sites on

federal lands. The Abandoned Shipwreck Act of 1987 specifical y extended

protection to shipwrecks and mandated states in whose waters the wrecks

are located to manage them for the public good. More recently, the Sunken

Military Craft Act of 2005 established U.S. rights to any U.S. military craft

sunk anywhere in the world and recognizes the rights of other sovereign

nations to their sunken ships and planes in U.S. waters. International y, the

The Maritime Heritage of Florida · 413

UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heri-

tage has been ratified. Although the United States is not a signatory to the

Convention, the United States does recognize the benefits of the Conven-

tion’s Best Practices for shipwrecks and other underwater cultural heritage

sites.

At the state level, Chapter 267 of the Florida Statutes, the Florida Histori-

cal Resources Act, proclaims that “all treasure trove, artifacts, and objects

having historical or archaeological value which have been abandoned on

state-owned submerged bottom lands belong to the people of Florida.” The

management of these heritage resources is the responsibility of the Florida

Department of State’s Division of Historical Resources. Within the Divi-

sion, the Bureau of Archaeological Research’s (BAR) Underwater Archaeol-

ogy Program is responsible for managing submerged heritage sites on state

lands. One of its more successful programs is the Underwater Archaeo-

logical Preserves and the Florida Maritime Heritage Trail. The Preserves are

historic shipwrecks around the state that are interpreted for the public while

the Trail consists of informational literature on six coastal heritage themes

including shipwrecks, lighthouses, coastal communities, coastal forts, envi-

ronments, and ports.

Despite, or perhaps because of, Florida’s uncommon wealth of mari-

proof

time heritage sites, many of our state’s underwater sites are under threat of

damage or destruction. Rampant construction and development threaten

coastal prehistoric and colonial sites. Florida’s draw as a scuba diving desti-

nation leads tens of thousands of visitors a year to the state’s historic ship-

wrecks and delicate coral reefs. Unfortunately, many divers, either ignorant

or uncaring of state law, take “souvenirs,” and in the process both damage

archaeological context and destroy the marine ecosystem. So-called “trea-

sure hunters” cause untold destruction of Florida’s underwater cultural and

ecological resources in the greedy, and usual y futile, quest for riches. Flor-

ida historians and archaeologists urge everyone to be aware and to act as

stewards to ensure that all of Florida’s maritime heritage sites are protected

and preserved for future generations to enjoy.

Bibliography

Bense, Judith.

Presidio

Santa

María

de

Galve:

A

Struggle

for

Survival

in

Colonial

Spanish

Pensacola

. Ripley P. Bullen Series. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003.

Buker, George E.

Jacksonvil e:

Riverport-Seaport

. Columbia: University of South Carolina

Press, 1992.

414 · Del a A. Scott-Ireton and Amy M. Mitchell-Cook

Coker, William S., and Thomas D. Watson.

Indian

Traders

of

the

Southeastern

Spanish

Borderlands:

Panton,

Leslie

&

Company

and

John

Forbes

&

Company,

1783–1847

. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1986.

Colburn, David R., and Lance DeHaven-Smith.

Florida’s

Megatrends:

Critical

Issues

in

Florida

. 2nd ed. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2010.

Dibble, Ernest.

Ante-Bel um

Pensacola

and

the

Military

Presence

, Volume III. Pensacola, Fla.: Pensacola Bicentennial Series, 1974.

Gannon, Michael.

Operation

Drumbeat:

The

Dramatic

True

Story

of

Germany’s

First

U-boat

Attacks

along

the

American

Coast

in

World

War

II

. New York: Harper and Row, 1990.

Hoffman, Paul E.

Florida’s

Frontiers

. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001.