The History of White People (5 page)

Read The History of White People Online

Authors: Nell Irvin Painter

Tags: #History, #Politics, #bought-and-paid-for, #Non-Fiction, #Sociology

Others of Caesar’s comments fit poorly into the lore of Teutonists. Consider the central role of women in war. As soothsayers, Caesar notes, women decide when to wage war, and once an enemy is engaged, women and children accompany their warriors into the field to bolster their bravery.

13

Latter-day Teutonists made war a strictly characteristically masculine affair.

C

AESAR’S WAS

also the first direct Roman report regarding the people of Britain. He obviously knew more about Germani than about Britons, but this lack of knowledge hardly prevented him from describing and judging those peoples across the Channel. He had visited only the coast of southeast Kent and the mouth of the Thames. Even so, he writes confidently of the interior. Britons there, he says, live by hunting and gathering and claim to be original inhabitants. They eat meat and milk, dress in skins, and dye their bodies blue with woad, which makes them “appear more frightening in battle. They have long hair and shave their bodies, all except for the head and upper lip.” And then there is, again, sex. In contrast to the Germans’ abstinence, in Britain “groups of ten or twelve men share their wives in common, particularly between brothers or father and sons. Any offspring are held to be the children of him to whom the maiden was brought first.”

14

All along, Britons contrast poorly with Belgic immigrants from the west bank of the Rhine who had supplanted the natives on England’s southern coast and gone on to live quite civilized lives, farming peacefully like the Gauls only a day’s sail away on the mainland.

C

AESAR’S

G

ALLIC

W

AR

endures as the pioneering—and primary—description of ancient Gauls and Germani. Its information, as we have seen, ranges widely, and it inspired those who followed through the centuries. Well into the 1800s,

The Gallic War

was cited as the source of what then seemed immutable truth: the notion of the river Rhine as a dividing line between permanently dissimilar peoples. Regrettably, this notion distorts Caesar’s views, transforming what he saw as manifestations of conquest and commerce into inherent racial difference. During Caesar’s own time, the Rhine was not yet thought to separate peoples according to essential differences.

G

AIUS

P

LINIUS

S

ECUNDUS

, Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE), wrote a century after Caesar, completing his

Natural History

in 77 CE. Two years later he died the death of a scientist—while witnessing the eruption of Mount Vesuvius near Naples that buried Pompeii and Herculaneum. The

Natural History

contains thirty-seven “books” of varying length—book 7, “Man,” for instance, is only thirty pages long in current book publication. Aiming to sum up all existing knowledge and explain the nature of all things, Pliny drew heavily upon both Greek and Roman authorities. In book 7, Pliny praises Julius Caesar as “the most outstanding person in respect of his mental vigour.”

15

To this accumulated knowledge Pliny added the fruit of his own military experience in Germany from 46 CE. The result is an extravagant, entertaining, and comprehensive work of 600-plus pages all told in English translation.

Like most ancient and medieval scholars, Pliny divides the earth into three parts—Europe, Asia, and Africa—and begins, as might be expected, with Europe. His Roman Europe, the “nurse of the people who have conquered all nations, and by far the most beautiful region of the earth,” occupies at least half the world. Again as might be expected, he deems his native Italy the best place in the universe, “ruler and second mother of the world” and “the most beautiful of all lands, endowed with all that wins Nature’s crown.” Without a doubt, the gods themselves had chosen Italy to unite and civilize the world, to “become the sole parent of all races throughout the world.”

16

Pliny’s book 7, focusing on humankind generally, includes Scythians and the now better-known Germani. They are cannibals all. The Transalpine tribes of Germany, for example, are depicted as a brutal bunch, practicing “human sacrifice, which is not far short of eating human flesh,” while out to the east, “some Scythian tribes—indeed a large percentage of them—feed on human bodies.” Picking up on his forebears Hippocrates and Herodotus, Pliny locates the Scythian cannibals ten days’ journey north of the river Borysthenes (the Dnieper). Among other uncivilized habits, they drink out of human skulls and use scalps “with the hair attached as napkins [protective material] to cover their chests.” Moving ever farther east and south, thirteen days’ travel beyond the Dnieper, the Sauromatae or Amazons still live, eating only every two days. Next to them can be found the Arimaspi, “a people noted for having one eye in the middle of their forehead.” There are also “certain people” born in Albania with keen-sighted, grayish-green eyes; “bald from childhood, they see more at night than during the day.”

17

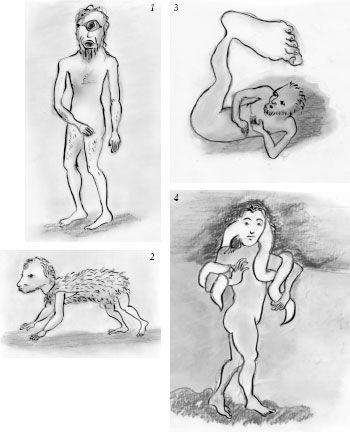

Indeed, Pliny’s catalog of humankind includes an amazing number of freakish peoples. In addition to the one-eyed folk, it describes others who grow a foot so big they pull it over their heads for shade from the sun. Still others come into the world with heads like those of dogs. So strong were Pliny’s fantastic notions that over a thousand years later, medieval English texts show these monstrous peoples as illustrating several varieties of mankind. (See figures 2.1–4, Monstrous people: Cyclops, Dog-Head, Sciopod, and Panotii.)

The thrilling notion that monstrous peoples existed out there in the wide, wide world survived well into Enlightenment science. Carolus Linnaeus, the eighteenth-century father of taxonomy, invented a revolutionary system that laid a durable groundwork for the naming and classifying of plants and animals. Yet even this scientific pioneer included a category of monstrous people in his classic work

Systema naturae

, and monsters remained part of the accepted scientific view of humanity until Johann Friedrich Blumenbach disproved their existence in his Ph.D. dissertation of 1775. It says a great deal about the intellectual inertia of medieval Western society that the notions to be found in Pliny’s

Natural History

held on for fifteen hundred years. Eventually, of course, Pliny’s encyclopedia faded into obscurity, as Europeans began to learn more of the world. Meanwhile, a work contemporaneous to Pliny’s passed muster as scientific truth among white race theorists well into our times.

E

ARLY IN

his illustrious writing career, the Roman historian Cornelius Tacitus (56–after 117 CE) wrote a short book entitled

De origine et situ Germanorum,

known commonly as

Germania

(98 CE).

*

A member of the Roman elite from either northern Italy or southeastern France, Tacitus was an accomplished orator and author. His major works,

The Histories

and

The Annals

, tell the story of the Roman empire, and his minor works consist of

Germania

, a biography of his father-in-law, Agricola, and a book on rhetoric entitled

Dialogus

. With the end of antiquity, Tacitus’s more important works lost currency, but within the history of white people, his reputation rests on

Germania

, more precisely on a myopic interpretation of

Germania

’s pronouncements on German endogamy.

Figs. 2.1–4. Monstrous people: Cyclops, Dog-Head, Sciopod, drawn by Nell Painter from Thomas de Cantimpré Panotii, drawn by Nell Painter, after the Cotton Tiberius MS of the British Library.

Like Caesar, whose work he echoes, Tacitus draws a line between tamer Gauls west of the Rhine and wild Germani to the east. Recognizing the importance of migration and conquest, Tacitus agrees with Caesar that the term

Germania

is of recent coinage. Tacitus explains—in phrases now quite confusing—that “since those who first crossed over the Rhine and drove out the Gauls (and now are called the Tungri) were at that time called Germani. Thus the name of a tribe, and not of a people, gradually became dominant, with the result that they were all called Germani, at first by the conquered from the name of the conquerors because of fear, and then, once the name had been devised, also by the Germani themselves.”

18

Distinguishing in some mysterious fashion between tribes and peoples, Tacitus is saying here that a tribe called Germani migrated into the territory of people whom the Romans once called Gauls but now call Tungri and conquered them. All of them came to be known as Germani. This garbled explanation may not illuminate what happened, but it does show how migration, conquest, and historical change influence the outlines of an ethnic category.

For Tacitus, as for “the divine Caesar,” warfare is uppermost in the mind, as barbarian warriors continued to serve widely in armies of the Roman empire. Tacitus also remembers the Gauls of former times as powerful enemies, but now, firmly conquered, they are settled and civilized. Habituated to Roman delicacies like wine, the Gauls have lost their bellicose masculinity and tipped toward effeminacy. Meanwhile, those noble savages, the Germani, largely retain their barbaric vigor by dint of warlike standoffishness, even as cupidity has been drawing them toward the allures of civilization: “They take particular pleasure in the gifts of neighbouring tribes, sent not only by individuals but also by whole communities: choice horses, splendid weapons, ornamental discs and torques; we have now taught them to take money also.”

19

German men constantly bear arms, for warfare represents their coming of age and their citizenship. Whenever they grow sluggish from sustained peace and leisure, privileged young men pick fights. It is through fighting, not trade or politics, that they accumulate prestige and support a large body of free and enslaved retainers. “To drink away the day and night disgraces no one. Brawls are frequent, as is normal among the intoxicated, and seldom end in mere abuse, but more often in slaughter and bloodshed.” Here Tacitus spies weakness and a foolproof means of vanquishing German warlords: “[if] one indulges their drunkenness by supplying as much as they long for, they will as soon succumb to vices as to arms.”

20

Even so, conquest of the Germani is not a likely prospect according to Tacitus, who etches the Roman empire’s political boundaries more deeply than Caesar and highlights the uniqueness of the Germani off on the empire’s far eastern side. Moreover,

Germania

downplays many differences within German tribes and instead pronounces the liberty and warfare characteristic of all small-scale societies as inherently Germanic traits.

21

Thus the failure of the Romans to subdue the Germani flows not from Roman shortcomings but from a particularly German virility. Perhaps their avoidance of the vices of civilization, or their sexual abstinence and its attendant potency, protects them from conquest. These qualities as they appear in

Germania

—warfare, masculinity, and barbarism—lie at the base of modern ethnogender stereotyping.

Looking backward, we may find it puzzling that both Tacitus and Caesar critique the effects of Roman civilization. After all, the vast Roman empire lasted some five hundred years and laid the linguistic, legal, architectural, and political foundations of the Western world. How could eminent citizens of this great empire squeeze out admiration for the dirty, bellicose, and funny-looking barbarians to the north? The answer lies in notions of masculinity circulating among a nobility based on military conquest. According to this ideology, peace brings weakness; peace saps virility. The wildness of the Germani recalls a young manhood lost to the Roman empire.

Long a critic of imperial Rome’s luxury and decadence, Tacitus found in the rough Germani a freedom-loving people embodying the older, better values of Augustinian times. Their homeland may be ugly and its climate cruel, but its simple folk possess a certain charm born of freedom, frequently manifested as anarchy and fighting, and the chastity that Caesar also noted.

22

To Tacitus, rude German simplicity trumps Roman decadence: “In every home they grow up, naked and filthy, into those long limbs and large bodies that amaze us so. Each child suckles at his own mother’s breasts, not handed over to slave girls and nurses…. Love comes late to the young men, and their virility is not drained thereby. Nor are maidens hurried along.”

23