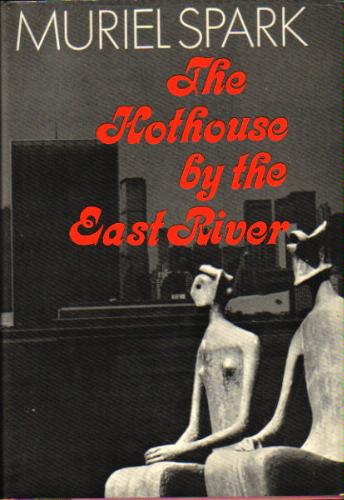

The Hothouse by the East River

Read The Hothouse by the East River Online

Authors: Muriel Spark

MURIEL SPARK

The Hothouse by the East River

I

If it were only true that

all’s well that ends well, if only it were true.

She

stamps her right foot.

She

says, ‘I’ll try the other one,’ sitting down to let the salesman lift her left

foot and nicely interlock it with the other shoe.

He

says, ‘They fit like a glove.’ The voice is foreignly correct and dutiful.

She

stands, now, and walks a little space to the mirror, watching first the shoes

as she walks, and then, half-turning, her leg’s reflection. It is a hot, hot

day of July in hot New York. She looks next at the heel.

She

looks over at the other shoes on the floor beside the chair, three of them

beside their three open boxes and two worn shoes lying on their sides. Finally,

she glances at the salesman.

He

focuses his eyes on the shoes.

Now,

once more, it is evening and her husband has come in.

She

sits by the window, speaking to him against the purr of the air-conditioner,

but looking away — out across the East River as if he were standing in the air

beyond the window pane. He stands in the middle of the room behind her and

listens.

She

says, ‘I went shopping. I went to a shoe store for some shoes. You won’t

believe me, what happened.’

He

says, ‘Well, what was it?’

She

says, ‘You won’t believe me, that’s the trouble. You aren’t sure that you’ll

believe me.’

‘How do

I know if you don’t tell me what it is?’

‘You’ll

believe me, yes, but you won’t believe that it really happened. What’s the use

of telling you? You don’t feel sure of my facts.’

‘Oh tell

me anyway,’ he says, as if he is not really interested.

‘Paul,’

she says, ‘I recognised a salesman in a shoe store today. He used to be a

prisoner of war in England.’

‘Which

P.O.W.?’

‘Kiel.’

‘Which

Kiel?’

‘Helmut

Kiel. Which one do you think?’

‘There

was Claus, also Kiel.’

‘Oh,

that little mess, that lop-sided one who read the books on ballet?’

‘Yes,

Claus Kiel.’

‘Well,

I’m not talking about him. I’m talking about Helmut Kiel. You know who I mean

by “Kiel”. Why have you brought up Claus Kiel?’

Paul

thinks: She doesn’t turn her head, she watches the East River.

One day

he thought he had caught her, in profile, as he moved closer to her, smiling at

Welfare Island as if it were someone she recognised. The little island was only

a mass of leafage, seen from the window. She could not possibly have seen a

person so far away down there.

Is it

possible that she is smiling again, he thinks; could she be smiling to herself,

retaining humorous reflections to herself? Is she sly and sophisticated, not

mad after all? But it isn’t possible, he thinks; she is like a child, the way

she comes out with everything at this hour of the evening.

She

tells him everything that comes into her head at this hour of the evening and

it is for him to discover whether what she says is true or whether she has

imagined it. But has she decided on this course, or can’t she help it? How

false, how true?

It is

true that in the past winter he has seemed to catch her concealing a smile at

the red Pepsi-Cola sign on the far bank of the river. Now he thinks of the

phrase, ‘tongue in cheek’, and is confused between what it means and how it

would work if Elsa, with her head averted towards the river, actually put her

tongue in her cheek, which she does not.

And

Paul, still standing in the middle of the carpet, then looks at her shadow. He

sees her shadow cast on the curtain, not on the floor where it should be

according to the position of the setting sun from the window bay behind her,

cross-town to the West Side. He sees her shadow, as he has seen it many times

before, cast once more unnaturally.

Although

he has expected it, he turns away his head at the sight.

‘Paul,’

she says, still gazing at the river, ‘go and get us a drink.’

Their

son, Pierre, came to see them last night. He said, while they were discussing,

by habit, in the hail, the problem of Mother: ‘She is not such a fool.’

‘Then I

am the fool, to spend my money on Garven.’

‘She’s

got to have Garven.’ He uttered this like a threat, intensifying his voice to

scare away the opposition that he knew to be prowling.

Garven

Bey is her analyst. Pierre is anxious that his mother should not go back into

the clinic and so upset his peace of mind. Moreover, Pierre knows it was not

his father’s money that went so vastly on Garven, but the surface-dust, the top

silt, merely, of his mother’s fortune.

Last

night, Paul said, as his son was leaving, ‘What did you think she looked like

tonight?’

‘All

right. There’s definitely something strange, of course…’

Paul

said goodnight abruptly, almost satisfied that his son had still not noticed

the precise cause of the strangeness.

Paul

cannot acknowledge it. A mirage, that shadow of hers. Not a fact.

She

gazes out of the window. ‘Paul, go and get a drink.’

But

Paul stands on. He says to her as she sits by the window, ‘Are you serious

about this man in the shoe shop?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then,

Elsa, I should say you have imagined Helmut Kiel. This is in the imaginative

category, almost definitely. You couldn’t have come across him in a shoe store.

He died in prison with only himself to thank for it. You should tell Garven of

this experience.’

‘All

right.’

‘What

shoe shop was it?’

‘Melinda’s

at Madison Avenue. At least I think so.’

‘Are

you smiling, there?’

‘No.

Why don’t you make a drink?’

‘He

died in prison six, seven years after the war.’

She

laughs. Then she says, ‘I see what you mean.’

‘What?’

‘Plainly

you are not speaking literally.’

‘I

think I’ll have a drink.’ But he does not go. He thinks, she has become a

mocker, she wasn’t always like this. It’s I who have made her so.

She

sits immobile; and now, to his mind, she is real estate like the source of her

money. She sits, well-dressed with her pretty hair-do and careful make-up, but

sits solidly, as on valuable land-property painted up like a deteriorating

building that has not yet been pulled down to make way for those high steel

structures, her daughter and her son. So Paul’s mind ripples over the surface.

And he

thinks to himself, deliberately, word by word: I must pull myself together. She

is mad.

The Pan

Am sign on the far bank of the river flicks on and off. She seems to be

catching a sudden unexpected glimpse of the United Nations building, which has

been standing there all the time, and she shudders.

‘Are

you cold?’ he says. ‘These air-conditioners are too old. They aren’t right.’

‘They

can be treacherous,’ she says.

‘Elsa,’

he says, ‘do you feel chilly? Why don’t we get a modern system?’

She

laughs out of the window.

He

speaks again, meaning to win her round, meaning to insinuate an idea into her

head that might fetch her back to reason, presuming she is departing from

reason once more.

‘The

temperature touched a hundred and one at noon. The highways have buckled, many

places.’

She has

turned her head towards the dark mass of Welfare Island.

He

feels he has probably failed in his attempt to say, ‘You are suffering from the

heat, your imagination…‘ He feels he might be wrong, he is not sure, as yet,

if she is going to have a relapse. This has happened before, he thinks, here in

this room I have stood, she has sat, how many times?

He

says, ‘What’s the name of the shoe store?’

‘Melinda’s,

Madison Avenue somewhere near Fifty-fifth, Fifty-sixth — might be

Fifty-seventh.’

He

says, ‘Upper Fifties and Madison. It still can’t be less than ninety-eight.’

She

says to the East River: ‘He means ninety-eight degrees — the temperature.’

Then, still looking out of the window she says, ‘Paul, get me a drink. I’ll

have vodka on the rocks, please.’

She is

looking for something out there. The sun has gone down. Yes, she is looking out

for it again. Silently Paul says to himself: ‘It’s not there.’ And again,

‘There’s nothing there.’

‘The

heat out there has affected you,’ she says, her face still turned to the dark

blue river where it quivers with the ink-red reflection of the Pepsi-Cola sign

on the opposite bank. ‘It’s affected you, Paul,’ she says in her tranquillity.

‘You’ve been standing there in that spot since you came in.’ She has moved her

head very little to the right and now she is looking at the United Nations

building with its patches of lighted windows. ‘Since you came in,’ she says,

‘you’ve been standing there watching me, Paul. It’s the heat making you

suspicious. Today’s been the hottest on record for twelve years. Tomorrow is to

be worse. People are going mad in the streets. People coming home, men coming home,

will have riots in their hearts and heads, never mind riots in the streets.’

He

wants to go and prepare their drinks, and has been thinking, ‘This has happened

before,’ but he will not move lest she should think she has taunted him into

it. He says, ‘Why did you go shopping for shoes in the heat?’

‘I had

swollen feet. I needed a bigger size.’

The

cunning answers of the crazy… He turns, now, and goes into the kitchen for

the ice. Will she incline her face towards him when he comes back?

He

breaks up the ice in the kitchen, he lingers. Eventually he returns, with face

and eyes strained in the effort.

New

York, home of the vivisectors of the mind, and of the mentally vivisected still

to be reassembled, of those who live intact, habitually wondering about their

states of sanity, and home of those whose minds have been dead, bearing the

scars of resurrection: New York heaves outside the consultant’s office,

agitating all around her about her ears.

He

looks across from his armchair to hers (for he does not believe in the couch;

to relinquish it had been his first speciality) and says, ‘And then?’

‘I came

to Carthage.’

‘Carthage?’

She

says, ‘I could write a book.’

‘What

do you mean by Carthage?’ he says. ‘You say you came. You came, you say. Do you

mean here is Carthage?’

‘Here?’

He

says, ‘Well, sort of.’

‘No, it

was only a manner of speaking.’ She smiles to herself, as if to irritate him.

He is thrown, knowing vaguely that Carthage was an ancient city of ancient

times but unable to gather together all at once the many things he has probably

heard about Carthage.

She

says, in the absence of his reply, ‘I think I’m really all right, Garven.’

Garven is his first name. His claim is, ‘I get my patients right away on to a

first-name basis’; it is the second on the list of his specialities.

‘I’m

all right, Garven,’ she says again while he is still wending his way towards

Carthage.

‘Yes, I

hope so. But we’ve got a good bit of ground to cover yet, Elsa, you know.’

She

says, as if to irritate him, ‘Why do you say “cover”? Isn’t that a peculiar

word for you to use? I thought psychiatry was meant to uncover something. But

you say “cover”. You said “We’ve got a good bit of ground to cover yet”—.’

‘I

know, I know.’ He places his hands out before him, palms downward, to hush her

up. He then explains the meaning of ‘cover up’ in its current social usage; he

explains bitterly with extreme care.