The House by the Dvina

Read The House by the Dvina Online

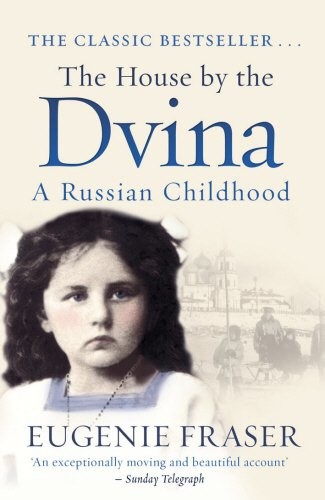

Authors: Eugenie Fraser

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #General, #History, #Historical, #Reference, #Genealogy & Heraldry

House by the DvinaI.M.M.M.

reminiscences

A.K.

The House by the Dvina

A Russian Childhood

EUGENIE FRASER

A unique and moving account of life in Russia before, during and immediately after the Revolution, The House by the Dvina is the fascinating story of two families, separated in culture and geography, but bound together by a Russian-Scottish marriage. It includes episodes as romantic and dramatic as any fiction: the purchase by the authorТs great-grandfather of a peasant girl with whom he had fallen in love, the desperate journey by sledge in the depths of winter made by her grandmother to intercede for her husband with Tsar Aleksandr II, the extraordinary courtship of her parents, and her Scottish granny being caught up in the abortive revolution of 1905.Eugenie Fraser herself was brought up in Russia but was taken on visits to Scotland. She marvellously evokes the reactions of a child of two totally different environments, sets of customs and family backgrounds. The characters on both sides as beautifully drawn and splendidly memorable.

CONTENTS

When All Was Young

Part II

Before the Storm

Part III

The Darkening Skies

Part IV

Change and Devastation

Part V

Farewell House and Farewell Home

Epilogue

To my father

WHEN ALL WAS YOUNG

CHAPTER

ONE

1912

I remember the station. Nikolayevsky Vokzal, it was called in those days.

I remember the cold and darkness and my father standing beside me holding my hand. He has a small parcel in his other hand and keeps telling me over and over again that it is for me and that I am to open it after the train leaves the station. My mother, in a short sealskin jacket and small hat perched on her dark hair, is standing facing me. Beside her is Petya Emelyanoff, a young man and friend of the family. Petya is studying music at the Conservatoire in St Petersburg and is now going home for his Christmas vacation. He has been commissioned to take charge of me for the long journey to Archangel where he will hand me over to my grandmother. I had been staying with my mother and young brother for a short holiday in Scotland, in the house of my Scottish grandparents; and then in Hamburg where my father was involved in some business. There, before leaving for St Petersburg, I had developed pleurisy and became very ill. My parents, who were to remain in St Petersburg for some time, had decided that the clear, crisp air of the distant north might be better for my health than the prevailing damp and fog of St Petersburg. It was also necessary for me to be tutored for the entrance exam to the local gymnasium (grammar school) in Archangel where I was to begin my education the following autumn.

Other people had arrived to see me off, but their faces are long since forgotten. I remember a light flickering somewhere, the bright shafts lighting up the faces in our little group and then plunging us back into gloomy darkness. My parents kept talking and smiling anxiously as if trying to reassure me, but instead were unconsciously transferring their sadness and anxiety to me. This was my first separation. The first of many.

In front of us lay a journey of two nights and days. Endless forests and snows, flat fields broken by poor dark cottages sunk in snowdrifts and small grey stations flashing past. We shared a compartment with two young merchants travelling to Vologda. I was allotted the top bunk above Petya.

The train had departed and now I was eagerly unwrapping the parcel.

Sitting there curled up on the top bunk in my cosy isolation I gazed with wonder at my present. I had never been showered with too many sweets or presents, but there was a box of chocolates all to myself. It was not an ordinary box. The day before, my parents, my brother and I had gone for a walk along the Nevsky Prospect. It was a lovely winter morning. The sun, the frost and the glistening snow. Nevsky Prospect, always beautiful, was now preparing for Christmas and wore a festive air. The shops, jewel bright, were spilling over with their rich and varied merchandise, catching the eyes of the passers-by. We sauntered slowly along from window to window until we came to the shop of a confectioner renowned for his chocolates. Here, against a background of black and crimson, chocolate boxes were displayed. All were of the same strange design, fashioned in the shape of mice. Pale grey, complete with sparkling crimson collars, red bead eyes and silver tails that moved and trembled. All sizes. Repelling and yet fascinating, they attracted crowds of people. I could hardly bear to leave the window and longed to possess one of these boxes there and then, but no one had paid any attention to my demands. Now it lay on my lap. I opened the lid cautiously. There inside, wrapped in silver foil with tiny red collars round their necks, were chocolate mice laid out in compact neatness. I planned never to eat a single one of them. Never to spoil the smooth circle of these little creatures sitting in such orderly perfection, nose to tail. I played for a long time with that box, arranging and rearranging the chocolates but in the end, tiring, put it under my pillow.

Meanwhile, below me, Petya and the two young men were talking and laughing as if they had known each other all their lives. I sat, my legs dangling over the edge of the bunk, listening to the steady flow of conversation beyond my understanding. One of the young merchants was constantly laughing. He appeared to have an endless supply of jokes and droll remarks. At times, looking up at me, he would say something, or wink and smile, as if he and I were sharing some secret joke. “Nye tak li, Jenichka?” … “Is that not so, Jenichka?” he would ask me, and I, sensing his kindness, would eagerly nod my head and smile back, although I did not really know what it was all about. It was all very strange. I was not quite seven and travelling alone in the company of grown-up men.

By now the northern evening was closing in. It was impossible to see anything outside through the dark windows, frosted over in white ferns and mysterious forests and mountains. The wheels turning round kept a steady rhythm as if they were repeating something over and over again, something sad, something lonely.

The attendant came in, balancing a tray laden with tumblers of tea.

Hampers appeared. I watched with interest as they were opened, revealing the contents wrapped in white linen. These little hampers, usually packed with all kinds of home baking, played an important part on long journeys.

There would be a variety of “pirozhkis”, the pastries filled with chopped meat, mushrooms or eggs, the “vatrushkies”, the small flat tarts with sweet cottage cheese, soft cookies and spiced biscuits, rich and delectable, so dear to the Russian heart and stomach. I have a vague and distant picture of a young child sitting on that top bunk, contentedly swinging her legs and cheerfully accepting all that these young, good-natured men were passing up to her.

The whole of that journey is like a jigsaw puzzle with pieces missing. One of the young men produced a balalaika. He began to strum gently and sing in a soft tender voice some old, plaintive folksong. Petya joined in. This was the first time I had ever heard him sing. As I sat alone, apart from the others, listening to their voices falling and rising in deep sadness or suddenly changing into a song full of wild and gay abandon, it was as if something of Russia herself crept into my young heart. Neither I nor the other passengers crowding round the door of our compartment knew they were listening to a voice already famous in the far north. “Severny Solvei,” “The Northern Nightingale” he was affectionately named there. As a friend of the family he often visited our house. When asked to sing, he would sit down at the grand piano, strike a chord, and begin. I, no matter what I was doing, would leave everything and hurry so as to be able just to stand nearby and listen.

I donТt remember how long I sat listening to the singing and watching the people gathered around our compartment. I must have been very tired and in the end I fell asleep.

I was awakened suddenly by a great urgency. Everything was in darkness, relieved only by a small glimmering light. My three companions were sound asleep. I had to find the toilet room immediately, but had no idea where it might be. It had never occurred to anyone to show me where to go or explain anything. To waken Petya or any of his companions was out of the question. From a tender age I had been completely independent over private matters. I had been fully dressed when I fell asleep but someone had removed my shoes and covered me with a blanket. I climbed slowly down, carefully gripping the edge of the lower bunk with my feet so as not to waken Petya. I succeeded in reaching the door, but Petya, even in his sleep, must have been attuned to his responsibilities. He sat up immediately. СWhere are you going?” he called out irritably and then, not waiting for an answer, dragged open the door and pushed me in front of him to the toilet room at the end of the passage. “In you get,” he said, impatiently stretching and yawning, his flaxen hair standing on end and his eyes heavy with sleep. I hurried in, too relieved and thankful to think about anything. It was then I found myself in a terrible predicament. In my time, a child wore a white cotton bodice buttoned down the centre of the back. The underpants fastened to the bodice. I mastered the side buttons with comparative ease and expediently ignored the centre back button.

The day of the journey, my mother had helped to dress me. She securely fastened all buttons. I now stood, frantic with anxiety, twisting and turning the centre back button with mounting desperation. The simple remedy of tearing the button off never entered my young head.

In the end, I was forced to come out and in great mortification explain my difficulty. “Turn round!” Petya ordered abruptly, and as I did so, he lifted my dress, undid the offending button, gave my bare bottom a playful slap and pushed me back into the lavatory. The intense relief was only equalled by my outraged dignity, and the shameful humiliation of that experience remained with me for a long time. When I came out I displayed no gratitude, but hurried past him, clambered back on to my bunk, and lay there with my face turned to the wall.

Gradually the pale winter daylight filtered through the frost-laden windows. The attendant arrived bringing tea and “kalachi”, the round glossy rolls with a hole in the centre renowned all over Russia. People were awakening. There were sounds of laughing and talking. Another day had begun. Little by little the sun rose, flooding the carriage with a warm glow. I stood in the corridor, my face close to the window. By peering through a small corner of the window untouched by frost, it was possible to watch the winter landscape swiftly rushing past and vanishing for ever more. The everlasting telegraph poles, the stations appearing for a fleeting moment, the neat square stacks of logs piled high on a siding, and always the forest. The endless rows of birches, their curly heads silvered by the frost, snow-laden pines standing close together deep in their winter sleep. The high banks dazzling white against a wall of green and black. There was little sign of life. Only a bird, startled by the incoming monster, would fly up suddenly and vanish somewhere into the woods beyond.

As I stood at the window, I became aware that the train was slowing down.

A great activity began around me. The train was steaming into Vologda.

Passengers were gathering their belongings, running up and down the corridor calling on each other, kissing and saying their final goodbyes.

Some were leaving for their homes and others, like ourselves, were completing the first stage of their journey. Only one more night remained and tomorrow we would be in Archangel. Meanwhile we had to leave this train and take the line that went due north. Our two friends in the compartment were leaving us in Vologda. In front of them was a long journey by horse into the depth of the country, but first it was agreed that we would adjourn to the restaurant in the station. Petya helped me into my shuba Ч the furlined coat Ч and felt boots, and tied a shawl over my fur hat. We stepped down on to the station. After the overheated compartment, the bitter cold was almost unbearable, yet the crowd bustling all around us did not appear to be aware of it.

Vologda is an important junction. From here passengers were leaving for Siberia, to Archangel, Moscow and St Petersburg. Everywhere were people, their breaths emitting clouds of steam, jostling and pushing. All hurrying somewhere. They are all here. The poor and the rich with their unmistakable stamp of class and society. The peasant in his nondescript bulky clothing, his face patient and weatherbeaten, struggling along with his bundles. He is travelling “hard”, the cheapest possible way. The opulent “kupets”, the well-to-do trader and his young wife in a neat-fitting jacket and flowered kerchief framing her round face; the proud lady with her children, and governess, moving toward the first-class compartment. Her husband, no doubt a wealthy landowner or some important civil servant, is following behind. He has a detached and faintly bored expression. A group of young officers, dashing and debonair, are hurrying along bound on some journey, oblivious in their haste of the milling crowd around them. Here one is also aware of a faint, indefinable yet all-pervading atmosphere. In his magnificent prologue to Russian and Ludmilla, that magic fairytale, Pushkin called it “dookh”. The word conveys a mingling of many things, expressing all at once the spirit, sense, smell and the very breath of Russia. One can recognise it all over Russia. In towns and villages, rivers and fields and on the boundless steppes. Inside the restaurant there was a welcoming air, underlaid with the aroma of food, fresh linen, and burning wood. Against the far wall stood a high sideboard. On top were rows of coloured bottles, an assortment of items and a steaming samovar. We sat down at a table near the entrance. A waiter in a white apron brought a tray laden with a variety of “zakuska” Ч salted herring, caviar, dill cucumbers, mushrooms and of course the inevitable bottle of vodka. Other dishes followed. After the confinement in the train I was content just to sit and watch all that was going on around me. The men kept talking and laughing and heaping up my plate.