The Hundred Years War (6 page)

Read The Hundred Years War Online

Authors: Desmond Seward

In 1334 Pope Clement VI succeeded in arranging a peace conference between the English and the French. It took place in the autumn at Avignon. The English tried to discuss Edward’s claim to the throne of France, but the French refused even to consider the matter. Then the English asked for compensation in the shape of an enlarged Guyenne, free of any obligations to the French King and in full sovereignty. Indeed Edward may well have been ready to settle for this. But Philip was not prepared to give away a single foot of French soil—his final offer was a slight enlargement of Guyenne’s frontiers on condition that the duchy was held not by Edward but by one of Edward’s sons as a vassal of France. Philip VI believed that he was negotiating from a position of strength.

Edward now adopted a new strategy, attacking in France on three fronts with comparatively small armies. His interim objective may have been to strengthen his position in Guyenne while reinforcing the alliance with Flanders. In the spring of 1345 his Plantagenet cousin, Henry of Grosmont, Earl of Derby and future Duke of Lancaster, assisted by Sir Hugh Hastings, struck in upper Gascony. He caught the French off guard, capturing Bergerac and many other towns and castles; the latter included La Réole, which the English had lost in 1325 and which only fell after a determined siege of nine weeks. This stronghold, high above the river Gironde and forty miles from Bordeaux, enabled the English to regain the long-disputed Agenais. They also penetrated as far north as Angoulême, which they took by storm. Simultaneously Sir Thomas Dagworth took the offensive in Brittany, overrunning French garrisons.

The following spring there was a massive French counter-attack in the south-west, Duke John of Normandy besieging the Earl of Derby at Aiguillon (where the rivers Lot and Garonne meet). The Duke may not have had 100,000 troops as Froissart tells us, but he could well have had 20,000—a considerable proportion of the French military might. Edward now prepared his third front. Reading the chronicles with all their tales of chivalry and knightly deeds, one tends not to realize the surprisingly modern thoroughness and professionalism of his strategy.

The French anticipated an English invasion from Flanders. But Jacob van Artevelde had been overthrown and a pro-French count returned. Against all expectations Edward chose to launch his third front, and main attack, in Normandy. It may have been an accidental choice. Froissart heard that Edward actually set sail for Guyenne, but was blown back to the marchesof Cornwall, where, while waiting, he was advised to try Normandy instead by an important Norman lord, Godefroi d‘Harcourt, who had fallen foul of Philip VI and fled to England. He told Edward that the people of Normandy were not used to war, and that ‘there shall ye find great towns that be not walled, whereby your men shall have such winning, that they shall be the better thereby twenty years after’.

When King Edward sailed from Porchester on 5 July 1346 he had with him ‘a thousand ships, pinnaces and supply vessels’, carrying about 15,000 men. (This was a considerable logistic achievement; even the great host which his father had led—on land—to defeat at Bannockburn thirty years before had numbered no more than 18,000.) As one of the most successful expeditionary forces in English history its composition—knights, lancers, bowmen (mounted and on foot) and knifemen—is worth examining in detail. It is significant that there was a far larger proportion of volunteers than hitherto, attracted by the prospect of plunder; noblemen had no difficulty in recruiting big companies under ‘indentures of war’.

In 1346 an English man-at-arms was still armoured mainly in ‘chainmail’ of interlinked metal rings. A shirt of this mail, over a padded tunic, covered him from neck to knees and was laced on to a conical helmet which was open faced but which occasionally had a visor. (The great barrel helm was seldom worn in battle nowadays.) He had steel breastplates and plates on his arms, together with elbow pieces and articulated foot-guards over mail stockings. Over all he wore a short linen surcoat. English knights were noticeably old-fashioned compared to the French, for across the Channel Philip VI’s paladins had their shoulders and limbs also covered by plate, and helmets

(bascinets)

with hinged, snout-like visors which had breathing holes. Their surcoat had been replaced by the shorter leather

jupon.

The horses also wore armour, with plate for their heads and mail or leather for their flanks. The basic weapon of both English and French was a long straight sword, hung in front at first but later moved to the left side and balanced by a short dagger on the right (called a

misericord

or ‘mercy’ on account of being used to dispatch the mortally wounded). On horseback, a ten-foot lance was carried and a small, flat-iron-shaped shield, and sometimes a short, steel-hafted battle-axe. On foot the principal weapon was usually the halberd—a combined half-pike and axe.

(bascinets)

with hinged, snout-like visors which had breathing holes. Their surcoat had been replaced by the shorter leather

jupon.

The horses also wore armour, with plate for their heads and mail or leather for their flanks. The basic weapon of both English and French was a long straight sword, hung in front at first but later moved to the left side and balanced by a short dagger on the right (called a

misericord

or ‘mercy’ on account of being used to dispatch the mortally wounded). On horseback, a ten-foot lance was carried and a small, flat-iron-shaped shield, and sometimes a short, steel-hafted battle-axe. On foot the principal weapon was usually the halberd—a combined half-pike and axe.

Only the men-at-arms—a term which covered knightbannerets (paid 4s a day), knights bachelor (2s a day) and esquires (is a day)—could afford this enormously expensive equipment which (in theory at least) also required two armed valets and three mounts per man-at-arms—a warhorse, a packhorse for the armour and a palfrey to ride when not on the battlefield. Some men-at-arms who could only afford a single horse wore instead the lighter, cheaper brigandine which was a leather jacket sewn with thin, overlapping metal plates. The light lancers or

hobelars

(also is a day), who rode with the men-at-arms, made do with a metal hat, steel gauntlets and a ‘jack’—a short quilted coat stiffened with iron studs and rather like a modern flak-jacket.

hobelars

(also is a day), who rode with the men-at-arms, made do with a metal hat, steel gauntlets and a ‘jack’—a short quilted coat stiffened with iron studs and rather like a modern flak-jacket.

The jack was the armour of the more fortunate archers, whether mounted or on foot. Their weapon, the famous English long-bow, was to revolutionize military tactics. It was in fact of Welsh rather than English origin, having first come to attention in the twelfth century during campaigns in Gwent, where its ability to send an arrow through the thickness of a church door had much impressed the English. Since Edward I’s reign every village in England had contributed to a national pool of archers, every yokel being commanded by law to practise at the butts on Sundays. By 1346 the long-bow had become standardized, each archer carrying as many as two dozen arrows; further supplies were carried in carts. The long-bowmen could shoot ten or even twelve a minute, literally darkening the sky, and had a fighting range of over 150 yards with a plate-armour-piercing range of about sixty. There was a huge arsenal of bows and arrows in the Tower of London ; perhaps it was ironical that many of the bow-staves had been imported from Guyenne. The archer also carried either a sword, a billhook, an axe or a maul—a leaden mallet with a five-foot-long wooden handle.

Mounted archers on ponies first appeared in Edward III’s Scottish campaigns. They carried a lance and were paid 6d a day—the wage of a master craftsman. The King valued these archers so highly that he had a bodyguard of 200 mounted bowmen from Cheshire in green and white uniforms. Together, horse-archers and men-at-arms combined fire power and armour with the utmost mobility. Yet although increasingly employed, mounted archers were probably always outnumbered by foot archers. Nor must it be forgotten that they had to dismount when in action as they could not shoot from the saddle. It cannot be too much emphasized that all long-bowmen were essentially defensive troops who could only play a decisive part in a battle if they were attacked by an enemy advancing towards them over the right terrain.

The long-bow and its murderous potential were so far unknown outside the British Isles. The favourite missile weapon of the French was the crossbow, a complicated instrument with a bow reinforced by horn and sinew; to draw it the crossbowman had to place his foot in the stirrup at the front end of the bow, fasten the string on to a hook on his belt, which meant crouching down by bending his knees and back, and then stand up, pulling the string until it could be engaged in the trigger mechanism. The crossbow had sights and fired small, heavy arrows known as quarrels. Its advantages were its longer range and greater accuracy and velocity, its disadvantages being its weight (up to 20 lbs) and slow rate of fire—only four quarrels a minute, at best.

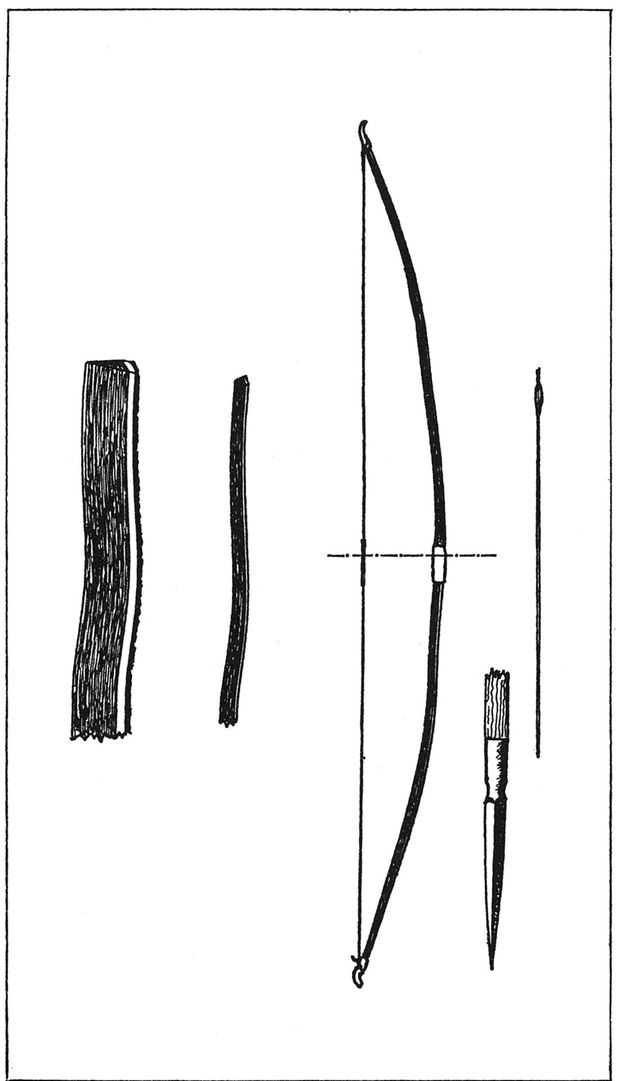

Long-bow

Though various woods were used in their construction, yew was the best. Bows were made from the main trunk or from thick boughs. Under the scaly bark is a layer of white sapwood that withstands tension very well. Beneath this is the red heartwood that is resistant to compression and gives drive to the bow. It is the combination of these two characteristics that results in the excellence of yew for making bows. The maker, or bowyer, had to follow the run of the grain in the wood so as to leave a layer of the sapwood, about

“ in thickness, on the outside of the heartwood. For this reason there are, almost invariably, irregularities in the curve of the yew long-bow.

“ in thickness, on the outside of the heartwood. For this reason there are, almost invariably, irregularities in the curve of the yew long-bow.

“ in thickness, on the outside of the heartwood. For this reason there are, almost invariably, irregularities in the curve of the yew long-bow.

“ in thickness, on the outside of the heartwood. For this reason there are, almost invariably, irregularities in the curve of the yew long-bow.The left-hand drawing shows a section of yew split from the main trunk. The next sketch shows a part of the rough stave with the thin layer of sapwood left on the outer surface. The two limbs were tapered to give a smooth curve when the bow was drawn. Horn tips with notches—or nocks, as they were called—for the bowstring were fitted to the better bows, but alternatively grooves were cut into the wood. The length of bows varied from about 5’ 8” to about 6’ 4”.

The arrows were about 30” in length and though many forms of head have been found, the so-called bodkin was generally accepted as the most deadly in warfare. It was basically a four-sided, case-hardened steel spike, as shown in the illustration. The string was of hemp with a spliced loop at one end and secured with a timber hitch at the other. The centre was served with thread to protect the strands from the abrasion of the arrow nock and from the fingers of the drawing hand, on which a leather shooting-glove was often worn.

With a typical war bow, having a draw-weight of 80—100 Ib, the instantaneous thrust on the string at the moment it checks the forward movement of the two limbs when it is shot is in the order of 400 Ib, so it needed to have a breaking strain of about 600 Ib to allow an adequate safety margin. but they produced plenty of noise, flame and acrid black smoke.

In addition King Edward seems to have had guns in 1346. This has been disputed, but the previous year he definitely ordered the manufacture of 100

ribaulds.

The

ribauld

was a bundle of many small-bore tubes—a bit like the

mitrailleuse

of the 1870s—mounted on a cart. Such weapons were seldom lethal, except to those firing them,

ribaulds.

The

ribauld

was a bundle of many small-bore tubes—a bit like the

mitrailleuse

of the 1870s—mounted on a cart. Such weapons were seldom lethal, except to those firing them,

Edward’s army also included large numbers of light infantry, who were paid 2d a day. These scouts and skirmishers were Welsh, Cornish and even Irish ‘kern’, armed with dirks and javelins—‘certain rascals that went on foot with great knives’. Their speciality was creeping beneath the men-at-arms’ horses and stabbing them in the belly, though they seem to have spent most of their time cutting the throats of the enemy wounded.

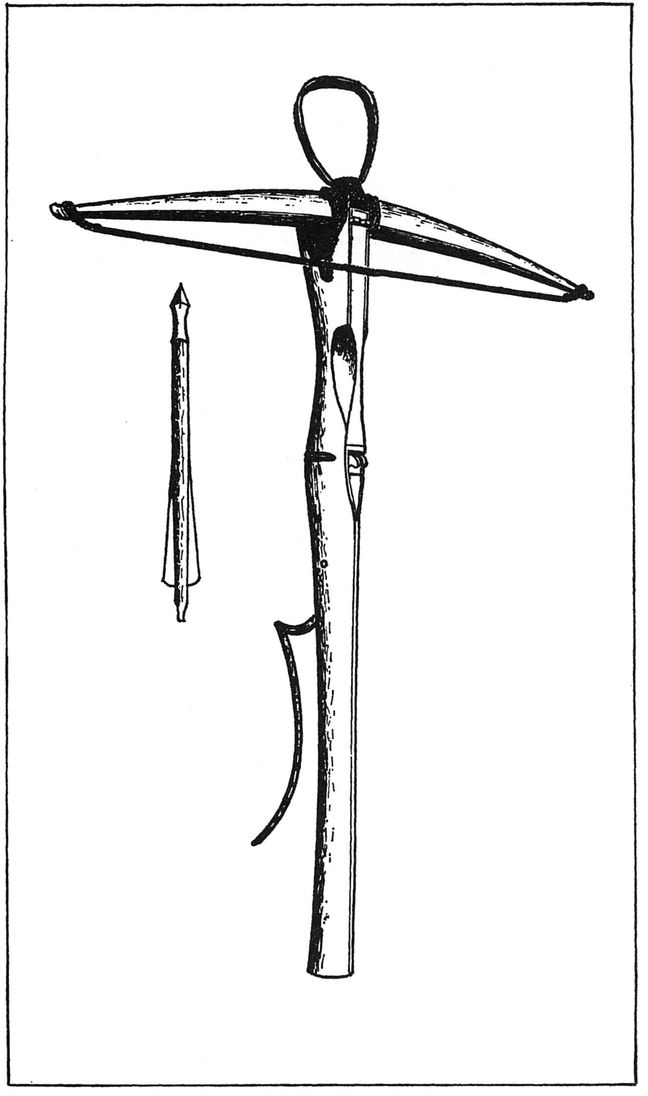

Crossbow

A military crossbow, one of the types used in the latter half of the fourteenth century and during the fifteenth century. The length overall is about 30”, the span of the bow about 26”, the weight about 4

lb.

lb.

lb.

lb.The stock or tiller is of wood, surfaced along the top with antler. The actual bow, or lath, is of composite construction, employing wood, horn and sinew. The fore end is fitted with an iron stirrup in which the foot is placed to facilitate spanning the bow—or drawing the string—with the belt and claw back to the revolving nut mechanism.

The bolt shown was the most widely used form for military purposes. It is about 15” long, the shaft is of wood and the flights, or vanes, are of leather, horn or wood. The rear end is tapered to fit between the lugs of the nut, while the fore end of the shaft is supported by a grooved rest, made from antler.

Other books

All Shook Up by Shelley Pearsall

Second Chance at Love (The MacKenna Born & Bred Trilogy) by Paradise, Tara

The Devil We Don't Know by Nonie Darwish

Frozen Stiff by Annelise Ryan

The Chalk Giants by Keith Roberts

In Rough Country by Joyce Carol Oates

Broken Fall: A D.I. Harland novella by Fergus McNeill

The Temptation of Your Touch by Teresa Medeiros