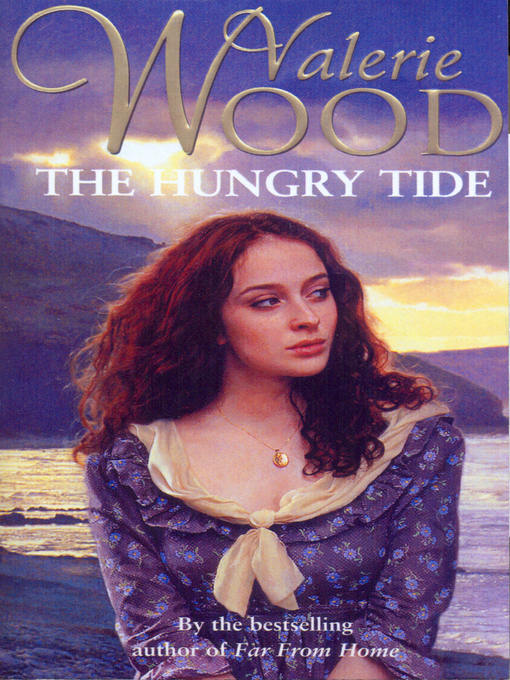

The Hungry Tide

Authors: Valerie Wood

In the slums of Hull, at the turn of the eighteenth century, lived Will and Maria Foster, constantly fighting a war against poverty, disease, and crime. Will was a whaler, wedded to the sea, and when tragedy struck, crippling him for life, it was John Rayner, nephew of the owner of the whaling fleet, who was to rescue the family. Will had saved the boy’s life on an arctic voyage and they were offered work and a home on the headlands of Holderness, on the estate owned by John Rayner’s wealthy family. And there, Will’s third child was born – Sarah, a bright and beautiful girl who was to prove the strength of the family.

As John Rayner, heir to the family lands and ships, watched Sarah grow into a serene and lovely woman, he became increasingly aware of his love for her, a love that was hopeless, for the gulf of wealth and social standing between them made marriage impossible.

Against the background of the sea, the wide skies of Holderness, and the frightening crumbling of the land that meant so much to them, their love story was played out to its final climax.

Val Wood is the first winner of the Catherine Cookson Prize which was set up in 1992 to celebrate the achievement of Dame Catherine Cookson.

The Hungry Tide

Val Wood

For my family with love

Acknowledgements

Poem

taken from

The Geography of East Yorks

, by T. S. Sheppard, FGS, FSA Scot. Reprinted from the

Journal of the Manchester Geographical Society

, parts III and IV, 1913, Sherratt & Hughes, 34 Cross Street, Manchester, 1914.

Sources of general information on whaling and its relevant industry obtained from the Kingston upon Hull Town Docks Museum. Further reading from the Malet Lambert Local History Originals,

The Hull Whale Fishery

by Jennifer C. Rowley and

A History of Hull

by Edward Gillett and Kenneth A. MacMahon.

Grateful loving thanks to my daughter Catherine Wood for patiently reading and re-reading the manuscript and to my family for welcoming the Foster family into our home.

Where life and beauty

Dwelt long ago,

The oozy rushes

And seaweed grow

And no-one sees

And no-one hears

And none remembers

The far off years.

It is the olden,

The sunken town

Which faintly murmurs

Far fathoms down

Like sea-winds breathing

It murmurs by,

And the sweet waters tremble

And sink and die.

The dark water slapped against the supports of the wooden wharves and staiths as the whaler drifted silently up the river. The mist which hovered over the water started to lift and, carried by the easterly wind, floated across the wharves and into the gardens of the merchants’ riverside houses. Through the quiet streets and alleyways it spread, carrying with it the stench of processed blubber from the Greenland Yards.

On it drifted, spreading wider through the town and reaching into the narrow, grimy Wyke Entry, where it clung to the blackened timbers of the mean old houses that leaned one into another, touching them with dampness.

The entry was silent, save for the rustling and scratching in the heap of rubbish which the wind had blown into a corner, for most of the occupants were still sleeping in the early dawn. Then came the sound of laboured breathing and the pad of running feet which directed themselves into the entry.

Maria wiped her mouth on a corner of the coarse sacking which was tied around her waist. Her grey eyes blinked involuntarily at the tears which had formed as she retched into a bucket by the door.

She’d been plagued by sickness with her other pregnancies and accepted this nauseous condition as one of the ordeals of motherhood to be endured until the fourth month, when miraculously it would disappear.

She straightened her back and took a deep breath. She didn’t feel like going to work this morning, the very thought of the smell of the fish which she and the other women had to load into the barrels at the staith side turned her stomach and made her want to vomit again.

But work she must: whilst Will was at sea the money she earned was very necessary. Food was dear, Tom had worn out his old boots and would need new ones this winter, and Will always insisted that money was put by in case the children were sick and needed medicine. Twice last winter cough syrup and poultices had had to be bought for Alice, who at three was a thin, pale-faced child with a weak chest.

Maria smiled when she thought of Will. He had already set sail when she found that she was pregnant again. She prayed that she would keep this child. She desperately wanted one more bairn, one more that they could love and keep and who would help her over the loss of the two babies who had died before Alice was born and who were buried in the churchyard.

Will had been sailing on whaling ships for eighteen years, since he was twelve years old, working for the same company as his father had before him, and he boasted often that Masterson’s were the best company in the port, looking after its men and bringing industry into the town with its whale oil and whalebone.

A generous bounty was given to the shipowners by the government, and the men were well paid for their labours. Will would have plenty of money in his pocket when he came home. There were losses, of course, and the men who worked these ships were well aware of the dangers lurking in the treacherous waters of the polar seas. Men were sometimes lost overboard and frostbite was common, with loss of fingers and toes.

Maria poured water from a jug into a bowl and rinsed her hands and face, and was brushing her long dark hair when she suddenly jumped, startled by a loud hammering on the door.

‘Maria, Maria!’ The voice outside was insistent.

‘Who is it?’ she whispered cautiously.

‘It’s me – Annie. Open ’door quick!’ She banged again even louder.

She’s early, thought Maria, as she unbolted the door. They were not due down at the Old Harbour side for at least another hour, it was only just daylight. She lifted the sneck. ‘Shush, tha’ll waken childre’. Don’t mek so much row. Alice has had a bad night with her cough.’

‘I’m sorry, love.’ Annie, her face pinched and grey, stood shivering on the doorstep. ‘But it’s urgent, I had to come.’

‘Come in quick, what is it, what’s up?’ Maria saw that her friend was distraught, her hair uncombed and without the shawl which the women always wore to keep out the cold river air and the smell of fish from their hair.

‘It’s ’

Polar Star

, she’s coming up ’river, I’ve just got ’message.’ Annie was breathless with anxiety. ‘We’ve got to go down to ’dock, summat’s wrong.’

Maria’s face paled. The whaler had set sail barely four months ago and to come home so soon, long before it was due, could only mean that something was seriously wrong.

‘Wait a minute while I see to ’bairns.’

She moved quietly to the corner of the room where the two children were still sleeping soundly, undisturbed by Annie at the door. She placed Tom’s outstretched arms back into the bed and covered both children more closely with the blanket. Softly she placed a kiss on their smooth foreheads before turning away, her mind in a turmoil.

If there had been a disaster on board the whaler, her children could already be fatherless and she a widow. That thought was always at the back of her mind although she tried not to dwell on it, but she was always conscious of the dangers that the men in the whaling ships encountered.

She wrapped a shawl around her shoulders and the two women hurried out of the narrow Wyke Entry, through the dark lanes and alleys, under the low archway which led into the wider Blackfryers’ Gate, and across to the long High Street which ran along the river towards the New Dock.

Although it was still early, lights were beginning to flicker as people prepared for work, and as they passed the big houses in the High Street they saw sleepy-eyed servants preparing for the day, drawing wide the heavy shutters and curtains at the tall windows and making ready for their masters’ and mistresses’ comfort.

‘Come on, this way, Annie.’ Maria ran through the narrow Chapel Staith towards the river. She had lived all of her life in the warren of buildings bounding the river and knew every corner, every alleyway.

The mist had risen above the water and swirled around the tall masts of the ships in the crowded waterway, but there was no sign of the whaler.

‘Hey,’ she shouted. ‘Any news of ’

Polar Star

?’

A seaman appeared on the deck of a Liverpool coaster and waved his hand towards the New Dock. ‘Aye. She passed an hour since!’

They picked their way over coils of rope and crates of merchandise that were piled high on the staith, their long woollen skirts brushing against the wet planking, and cut back down the next entry into the High Street.

Annie started to snivel. ‘What’ll we do, Maria, if our men ’aven’t come back? What about our poor bairns?’

Maria took hold of her arm and gave her a none too gentle shake. ‘We’ll worry about that when we have to, not before!’

But her brave words belied a fear that threatened to engulf her, for in truth she dared not think of life without Will. The hardship of coping without a husband did not deter her, for the whaler wives spent many lonely months whilst their men were at sea, but she would miss the loving and the tenderness which her gentle, honest Will bestowed on her and his children, and she loved him dearly.

They were joined by other women and some children as news spread of the

Polar Star

’s early return, and the sound of their boots and wooden pattens clattered on the cobbles as their numbers grew. Running now, they turned out of the narrow street into the wider Salthouse Lane to avoid the steadily increasing crush of men who were arriving for work at the shipyards and, as they came in sight of the Quay, Maria drew in her breath sharply. ‘She’s there. They’re unloading already.’

Visible at the eastern end of the dock, the masts of the whaler showed black against the brightening sky. The thud of ropes and canvas echoed through the quiet of the morning and a clatter of wood and iron rang out as the barrels of blubber were brought ashore, but the men on board were strangely silent, no whistling or shouting in their usual manner as they went about their tasks.

Maria joined a group of women standing together at the dock side, their shawls clutched tightly between tensed fingers. ‘Does anybody know what’s happened? What news of our men?’

Some of the women shook their heads indecisively as they waited. Others grumbled that there was no-one around to ask.

‘I want to know about my lad.’ An elderly woman clutched at Maria’s arm. ‘He’s all I’ve got now. His fayther went down two year sin’.’

‘Where’s ’mate?’ Maria called to one of the porters. ‘Who’s in charge?’

‘Don’t know,’ he replied. ‘Tha’d best try ’Dock Office. There’s been some trouble on board.’ He smiled sympathetically at the women and then turned back to load a barrel of blubber on to a wooden sled waiting at the quayside.

They all turned towards the Dock Office, hurrying now that there was a purpose in view, Maria striding ahead of them as if their elected leader. She could feel the women’s fear as silently they followed her, the tension spreading amongst them, and she tried to keep calm, unlike Annie who had given way to her emotions and was shaking nervously and wailing to herself as she scurried along at Maria’s side.

As they approached the building they saw a knot of seamen standing outside the door, some with bandaged hands, others leaning wearily against the wall chewing wads of tobacco. Some of the women recognized their own men and, crying out in relief, rushed towards them. Maria searched anxiously amongst the faces, but there was no sign of Will, his tall figure and mass of tangled red hair, so distinguishable from the average, was missing from the crowd.

The heavy wooden door opened and a clerk came out. He looked around at the group of waiting men and called out briskly, ‘Those who haven’t been paid off, come back in an hour to collect tha wages.’

He looked down at a paper in his hand and asked, ‘Is there a Mrs Bewley, Mrs Swinburn and Mrs Foster here?’