The Illusion of Victory (59 page)

Read The Illusion of Victory Online

Authors: Thomas Fleming

Woodrow Wilson told King George V of England to stop calling the Americans cousins and advised him that the term “Anglo-Saxons” was also out of date. The King later called him an “entirely cold academical professor —an odious man.”

C

OURTESY OF THE

L

IBRARY OF

C

ONGRESS

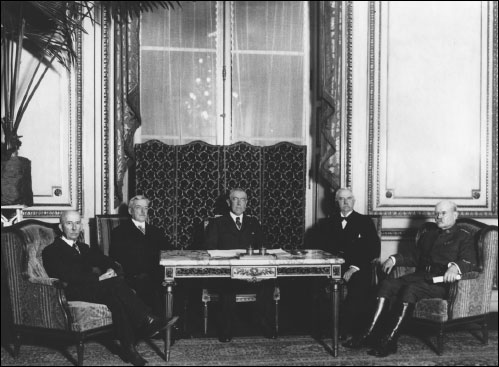

Many thought Wilson blundered in his selection of the American delegation at the Paris Peace Conference. From left to right, they were: Colonel Edward House, Secretary of State Robert Lansing, the president, retired diplomat Henry White and former chief of staff General Tasker Bliss. White was the only Republican. Wilson rejected advice to invite a leading Republican member of the Senate.

C

OURTESY OF

F

RANKLIN

D. R

OOSEVELT

L

IBRARY

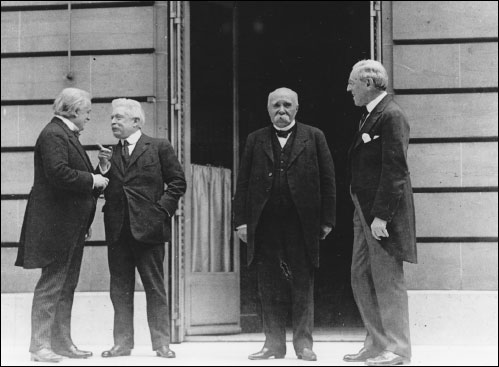

To speed up the interminable peace conference, major decisions were reserved for the “Big Four” (left to right): David Lloyd George, prime minister of Great Britain, Vittorio Orlando, premier of Italy, Georges Clemenceau, premier of France, and President Wilson. Orlando went home in a rage when Wilson appealed over his head to the Italian people.

C

OURTESY OF

F

RANKLIN

D. R

OOSEVELT

L

IBRARY

Woodrow Wilson salutes wellwishers from the upper deck of the liner George Washington on his return from Europe. With him is his physician and close friend, Admiral Cary Grayson, guardian of the president’s precarious health.

C

OURTESY OF

F

RANKLIN

D. R

OOSEVELT

L

IBRARY

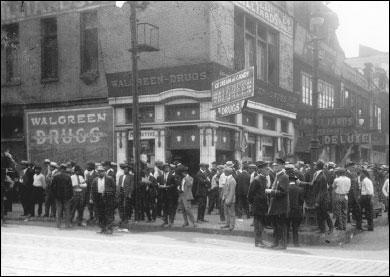

In the summer of 1919 race riots erupted in Washington D.C., Chicago and other cities. Here a crowd gathers on a Chicago corner. No fewer than 2,600 strikes, involving 4 million workers, also roiled the country. War-driven inflation had sent the cost of living soaring.

C

HICAGO

H

ISTORICAL

S

OCIETY

DN-0071297

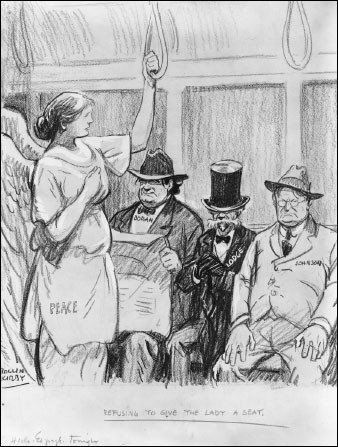

Many newspapers supported Wilson in the struggle over the peace treaty. Here, New York World cartoonist Rollin Kirby skewers three opponents, Senators Hiram Johnson, Henry Cabot Lodge and William Borah.

C

OURTESY OF THE

L

IBRARY OF

C

ONGRESS

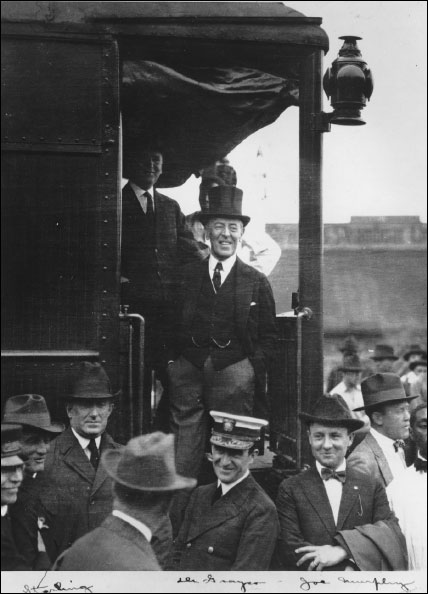

In St. Paul, one of the first stops on his 1919 speaking tour, Woodrow Wilson seemed rested and confident. He expected to rally people behind his version of the League of Nations. But attacks by ethnic groups and senatorial critics soon turned the trip into an exhausting nightmare.

C

OURTESY OF THE

L

IBRARY OF

C

ONGRESS

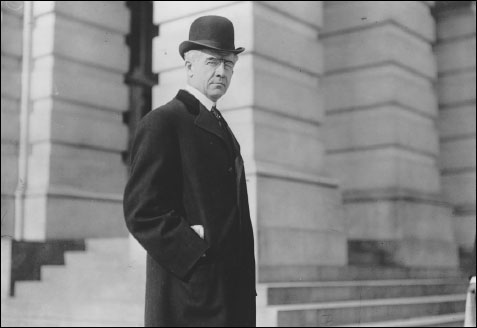

Dandyish Gilbert Hitchcock of Nebraska was the leader of the Senate Democrats in the struggle over the Versailles treaty. Afterward he called his vote against the amended treaty, cast on Wilson’s orders, the greatest mistake of his life.

C

OURTESY OF THE

L

IBRARY OF

C

ONGRESS

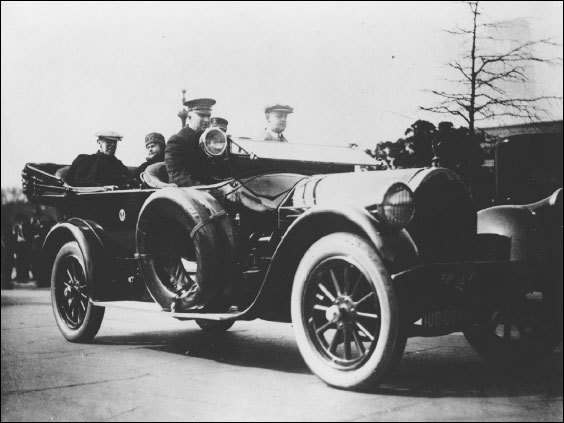

Woodrow Wilson and his wife take their first auto ride after the president’s cerebral thrombosis. White House Chief Usher Ike Hoover said: “There never was a moment when he was more than a shadow of his former self. He had changed from a giant to a pygmy.”

C

OURTESY OF THE

L

IBRARY OF

C

ONGRESS

Democratic presidential nominee Governor James Cox of Ohio and his running mate, Franklin D. Roosevelt, campaign at a Toledo parade. Backing Wilson’s call for a “great and solemn referendum” on the League of Nations, they were buried by a stupendous Republican landslide.

C

OURTESY OF

F

RANKLIN

D. R

OOSEVELT

L

IBRARY

PEACE THAT SURPASSES UNDERSTANDING II

One of the first things Woodrow Wilson said to Colonel House when they met at Brest on March 13, 1919, was a snarled rebuke:“Your dinner [with the foreign relations committees] was a failure as far as getting together was concerned.” Unflappable as always, House replied that the meeting still had some merit. It had diminished press criticism of Wilson’s neglect of Congress. Wilson grudgingly admitted this might be true.

The colonel refrained from pointing out that Wilson’s Boston speech had undermined the spirit of conciliation he had urged on the president. Nor did he rebuke Wilson for his even more intemperate remarks to the Democratic National Committee, the audience at the Metropolitan Opera House, and the committee from the Irish Race Convention. One wonders if the author of

Philip Dru

had begun to feel like Dr. Frankenstein. Had he created a monster that was running amok?

Wilson had put House in charge of the American delegation in his absence, and the colonel had continued to negotiate with French and British leaders. In her memoirs, Edith Wilson created a scene in which Wilson emerged from an extended conversation with House aboard the

George Washington

in Brest harbor looking dazed and horrified. Edith claims to have seized his hand and cried, “What is the matter? What has happened?”

The president supposedly replied,“House has given away everything I had won before we left Paris. He has compromised on every side, and so I have to start all over again and this time it will be harder because he has given the impression my delegates are not in sympathy with me.”

1

Again, we are dealing with something that Wilson almost certainly never said. For one thing, House did not board the

George Washington,

which had anchored out in Brest’s harbor. He had come down to Brest on Wilson’s special train and waited for him at the dock. But comments from other participants in the peace conference suggest there is a modicum of truth in the First Lady’s recollection. Wilson was extremely dissatisfied with the tenor and direction of the negotiations House had conducted while he was gone.

Aboard the train to Paris that night, House was frustrated by the presence of the French ambassador to the United States, Jules Jusserand, who prevented him from having a serious discussion with the president. But the next morning, before they left the train in Paris, the two men had a long talk. House told Wilson that negotiations on German reparations had gotten nowhere. The British and French refused to modify their astronomical demands. The French were also demanding the Saar basin, with its valuable coal mines, as promised in another secret treaty, and the creation of a “Rhenish Republic” in the Rhineland, which they would control. Both the French and the British wanted to separate the League of Nations from the treaty and conclude a peace with Germany as soon as possible.

House had not opposed the French demands; nor had he rejected the separation of the league and the treaty. He had begun to have grave doubts about Wilson’s obsession with the league to the detriment of almost everything else. Germany and much of the rest of central Europe were sliding into chaos and revolution. An immediate peace with Berlin seemed imperative. General Tasker Bliss, a fellow member of the peace commission, felt the same way. He had written a memorandum, saying that if an early peace were concluded with Germany, the American people might be willing to tackle other problems, including Soviet Russia.

2

Wilson’s response to these proposals was dismaying, from House’s point of view. The president rejected the transfer of the Rhineland and the Saar to France, because it violated the principle of self-determination. He was even more intransigent on separating the league and the treaty. House did not realize how much Wilson had become involved, politically and emo

tionally, with his critics in the U.S. Senate. The discouraged colonel glumly noted,“The President comes back very militant and determined to put the league into the peace treaty.”

House saw this as a tremendous, potentially earthshaking mistake. Perhaps he could not conceal this conviction. Perhaps he did not try very hard. After all, he was not merely Wilson’s unofficial mouthpiece now. At the Paris Peace Conference, Edward Mandell House was almost if not quite Woodrow Wilson’s equal. As a peace commissioner, he had one of the most important assignments in American diplomatic history. He desperately wanted this conference to succeed, not only for the sake of Wilson’s place in history, but for his own. Their disagreement marked the beginning of the end of the colonel’s partnership with Woodrow Wilson.

3

In Germany, American troops had moved into the Rhineland as part of an army of occupation. The Americans—and their British counterparts elsewhere in Germany—swiftly realized from the gaunt faces they saw on the street that the Germans were starving to death. The British began bombarding the War Office in London with horror stories. General Sir Herbert Plumer, commander of the British occupation army, said his soldiers could not stand the sight of hordes of skinny and bloated children pawing through the garbage in British camps. Minister of War Winston Churchill issued a statement, based on evidence he had seen from officers sent to Germany by the War Office: There was grave danger of “the entire collapse of the vital structure of German social and national life under the pressure of hunger and malnutrition.” One British journalist was particularly appalled by a visit to a maternity ward in a Cologne hospital. He described “rows of babies feverish from want of food, exhausted by privation to the point where their little limbs were like slender wands, their expression hopeless, and their faces full of pain.”

4

Germany was not the only nation without food. The disparate pieces of the Austro-Hungarian empire were also sinking into starvation and chaos. No one had stopped to figure out how to stitch together the economic connections that the armistice had severed. Prague was devoid of meat, rice, coffee and tea. Its factories had no coal. The death rate for children under 14 was 40 percent. In a Czech mining town, 116 out of 165 children

born in 1918 had already died. A wave of typhus was sweeping out of Russia into eastern Europe and Germany. Typhus was carried by lice, tiny crawling creatures that thrived on human bodies when there was no soap to wash them. Soap was made from a surplus of fats. When there was no surplus, the people consumed the fats and did without soap—with disastrous consequences.

On a fact-finding mission to Vienna, one of Colonel House’s top aides, Colonel Stephen Bonsal, saw with his own eyes the face of anarchy. As he strolled along one of the streets of the Ring, the circular heart of aristocratic Vienna, he was startled by the rattle of sabers and bursts of gunfire. Infantry and cavalry poured out of courtyards and confronted “a disorderly mob of men, women and barefooted children” emerging from the city’s working-class neighborhoods, heading toward the parliament buildings. As they drew nearer, Bonsal could see “how miserably clad they were” and he could hear their cries:“We are starving! Give us bread and jackets! We are famished and we freeze!”

Suddenly shots rang out, followed by volleys, and then by a fusillade. Policemen, soldiers and horses went down. Some of the workers ran away, but other “more resolute” groups pushed on. The troops opened fire with every weapon in their possession, and “soon the Ring was cleared of the living,” Bonsal wrote. “Here and there lay groups of dead and tangled masses of writhing wounded.” Among the dead was the pretty wife of a British engineer who had come to Vienna to help build factories and create jobs for the underclass. She had been caught in the crossfire while out for a stroll.

Next Bonsal saw something that made him realize what starving people will risk for food. Men and women crept from behind nearby buildings and began hacking chunks of meat from the dead horses, even though the troops continued to fire on them. Bonsal could only conclude that Vienna, the once magnificent capital of the Hapsburg empire, was on the brink of chaos.

5

More and more people began to wonder what the peacemakers in Paris were doing. Almost five months had passed since the armistice. From Rome, Pope Benedict XV pleaded for the end of the blockade and an early peace treaty. Colonel Henry Anderson, the leader of an American civilian-military commission to aid the Balkan states, issued a similar plea. He described children walking the streets of Bucharest,“their limbs black and blue with cold.”

“The slogan of Europe ought to be, ‘Get back to work,’” Herbert Hoover said.“To a great extent the whole production is stopped. . . . We have got to have peace as soon as possible.” hoover finally got the blockade lifted for Poland, Czechoslovakia, Rumania and Austria, but not for Germany or Hungary. Unfortunately, this concession made little difference in the desperate situation. The Italians, to reinforce their demands for the territory promised them in 1915, were blocking all attempts to ship food and fuel into eastern Europe.

6

Rome was also hard at work demolishing Woodrow Wilson’s image as the savior of the world. Day after day, Gabriele D’Annunzio, Italy’s best-known poet, published newspaper articles denouncing the president as the country’s chief enemy at the peace conference.“What peace will in the end be imposed on us, poor little ones of Christ?” the poet cried in his usual extravagant style. “A Gallic peace, a British peace, a star-spangled peace?” D’Annunzio had become devoted to the man he saw as the savior of Italy, Benito Mussolini.

7

The 1½ million American soldiers still in Europe were fighting a new enemy: boredom. At first, convinced that the war was not really over, the U.S. high command had insisted on tough training schedules. The result was endless hours of drilling and maneuvers in cold mud and colder rain. In a month or two, it dawned on the men that it was all meaningless. The newspapers made it clear that the German army had been demobilized as fast as it returned home. Raymond B. Fosdick, in charge of training-camp activities, reported with alarm on what he saw:“A battery that has fired 70,000 rounds in the Argonne fight going listlessly through the movements of ramming an empty shell into a gun for hours at a stretch . . . infantry drill in the muddy roads up and down which columns of American soldiers trudge listlessly and without spirit.”

8

The petty discipline of military life, the requirement to salute every passing officer, to maintain spotless, dust-free barracks, was another irritant. Disillusion with the “Great Adventure” began to seep through the ranks. It persisted, even when Pershing, realizing the peace conference was not going to end soon, began an elaborate sports program and made educational opportunities available in army-operated schools as well as in French universities.

Among the American soldiers in the 200,000-man Allied army of occupation, an unexpected development took shape. The doughboys found the Germans far more pleasant to deal with than the French, who had tried to wring additional francs out of every transaction. The French noted this warmth and found it irritating. The irritation soon got into their newspapers, and someone asked Pershing about it. He replied with characteristic bluntness that the Americans found the Germans likable—so what? They treated the Americans decently.“Our men have the sporting instinct. They don’t believe in hitting a man when he is down. There are some people who don’t seem to know what that sporting instinct means.” he meant the French, of course. Pershing had far more grudges against Clemenceau, Foch and company than he had against General Ludendorff.

9

As March ebbed into April with no sign of the end of the peace conference, Pershing began to ship some of the disgruntled doughboys home. Along with them went most of the women volunteers who had driven ambulances, nursed, and manned YMCA canteens. A surprising number of these volunteers had severe morale problems. Depression coruscated through the ranks. One woman, Margaret Deland, summed up the reason.“Over in America, we thought we knew something about the war . . . but when you get here the difference is [like] studying the laws of electricity and being struck by lightning.” Deland said the only way she kept sane was by concentrating on her “immediate little trivial foolish job.” If she lifted her eyes to the “black horizon,” she was in serious danger of “los[ing] my balance.”

10

When the guns fell silent, the black horizon loomed larger and larger in the souls of many of these women. One wrote an autobiographical novel that ended aboard a homeward-bound ship in a French port. While the volunteers waited to sail, military police in small boats rowed around and around the vessel to prevent suicides.

Demonstrating that this was fiction based on real experience was the fate of a gifted young poet, Gladys Cromwell, and her twin sister. The two women had worked for the Red Cross, which brought them into close contact with the carnage in the front lines. On the ship returning home, they revealed symptoms of deep depression but no one knew what to do about it.

One night, as dinner was being served, the cry of “man overboard” rang through the ship. The engines abruptly ceased, and an agitated doughboy charged into the dining hall to tell what he had seen. The Cromwell twins had been standing at the rail on a deserted lower deck. The soldier had strolled toward them, hoping to start a conversation. One of them stepped back, then raced to the rail and jumped over.

“Don’t!” cried the soldier and rushed to save the second woman. Before he could reach her, she too went over the side with an anguished scream. As she drifted away in the freezing water of the January Atlantic, she screamed again—then there was silence.