The Illustrated Gormenghast Trilogy (159 page)

Read The Illustrated Gormenghast Trilogy Online

Authors: Mervyn Peake

His fist was caught in the capacious paw of the rudder-nosed man, who signed to his servants to carry Titus to a low room where the walls from floor to ceiling were lined with glass cases, where, beautifully pinned to sheets of cork, a thousand moths spread out their wings in a great gesture of crucifixion.

It was in this room that Titus was given a bowl of soup which, in his weakness, he kept spilling, until the spoon was taken from him, and a small man with a chip out of his ear fed him gently as he lay, half-reclined, on a long wicker chair. Even before he was halfway through his bowl of soup he fell back on the cushions, and was within a moment or two drawn incontinently into the void of a deep sleep.

When he awoke the room was full of light. A blanket was up to his chin. On a barrel by his side was his only possession, an egg-shaped flint from the Tower of Gormenghast.

The chip-eared man came in.

‘Hullo there, you ruffian,’ he said. ‘Are you awake?’

Titus nodded his head.

‘Never known a scarecrow to sleep so long.’

‘

How

long?’ said Titus, raising himself on one elbow.

‘Nineteen hours,’ said the man. ‘Here’s your breakfast.’ He deposited a loaded tray at the side of the couch and then he turned away, but stopped at the door.

‘What’s your name, boy?’ he said.

‘Titus Groan.’

‘And where d’you come from?’

‘Gormenghast.’

‘

That’s

the word.

That’s

the word indeed. “Gormenghast.” If you said it once you said it twenty times.’

‘What! In my sleep?’

‘In your sleep. Over and over. Where is it, boy? This place. This Gormenghast.’

‘I don’t know,’ said Titus.

‘Ah,’ said the little man with the chip out of his ear, and he squinted at Titus sideways from under his eyebrows. ‘You don’t know, don’t you? That’s peculiar, now. But eat your breakfast. You must be hollow as a kettledrum.’

Titus sat up and began to eat, and as he ate he reached for the flint and moved his hand over its familiar contours. It was his only anchor. It was, for him, in microcosm, his home.

And while he gripped it, not in weakness or sentiment but for the sake of its density, and proof of its presence, and while the midday sunlight sifted itself to and fro across the room, a dreadful sound erupted in the courtyard and the open door of his room was all at once darkened, not by the chip-eared man but, more effectively, by the hindquarters of an enormous mule.

Titus, sitting bolt upright, stared incredulously at the rear of this great bristling beast whose tail was mercilessly thrashing its own body. A group of improbable muscles seldom brought into play started, now here, now there, across its shuddering rump. It fought

in situ

with something on the other side of the door until it forced its way inch by inch out into the courtyard again, taking a great piece of the wall with it. And all the time the hideous, sickening sound of hate; for there is something stirred up in the breasts of mules and camels when they have the scent of one another which darkens the imagination.

Jumping to his feet, Titus crossed the room and gazed with awe at the antagonists. He was no stranger to violence, but there was something peculiarly horrible about this duel. There they were, not thirty feet away, locked in deadly grapple, a conflict without scale.

In that camel were all the camels that had ever been. Blind with a hatred far beyond its own power to invent, it fought a world of mules; of mules that since the dawn of time have bared their teeth at their intrinsic foe.

What a setting was that cobbled yard, now warm and golden in the sunlight, the gutter of the building thronged with sparrows; the mulberry tree basking in the sunbeams, its leaves hanging quietly while the two beasts fought to kill.

By now the courtyard was agog with servants and there were shouts and countershouts and then a horrible quiet, for it could be seen that the mule’s teeth had met in the camel’s throat. Then came a wheeze like the sound of a tide sucked out of a cave; a shuffle of shingle, and the rattle of pebbles.

And yet that bite that would have killed a score of men appeared to be no more than an incident in this battle, for now it was the mule who lay beneath the weight of its enemy, and suffered great pain, for its jaw had been broken by a slam of the hoof and a paralysing butt of the head.

Sickened but thrilled, Titus took a step into the courtyard, and the first thing he saw was Muzzlehatch. This gentleman was giving orders with a peculiar detachment, mindless that he was stark naked except for a fireman’s helmet. A number of servants were unwinding an old but powerful-looking hose, one end of which had already been screwed into a vast brass hydrant. The other end was gurgling and spluttering in Muzzlehatch’s arms.

Its nozzle trained at the double-creature, the hose-pipe squirmed and jumped like a conger, and suddenly a long, flexible jet of ice-cold water leapt across the quadrangle.

This white jet, like a knife, pierced here and there, until, as though the bonfire of their hatred had been doused, the camel and the mule, relaxing their grips, got slowly to their feet, bleeding horribly, a cloud of animal heat rising around them.

Then every eye was turned to Muzzlehatch, who took off his brass helmet and placed it over his heart.

As though this were not peculiar enough, Titus was next to witness how Muzzlehatch ordered his servants to turn off the water, to seat themselves on the floor of the wet courtyard, and to keep silent, and all by the language of his expressive eyebrows alone. Then, more peculiar still, he was surprised to hear the naked man address the shuddering beasts from whose backs great clouds of steam were rising.

‘My atavistic, my inordinate friends,’ whispered Muzzlehatch in a voice like sandpaper, ‘I know full well that when you smell one another, then you grow restless, then you grow thoughtless, then you go … too far. I concede the ripe condition of your blood; the darkness of your native anger; the gulches of your ire. But listen to me with those ears of yours and fix your eyes upon me. Whatever your temptation, whatever your primordial hankering, yet’ (he addressed the camel), ‘yet you have no excuse in the world grown sick of excuses. It was not for you to charge the iron rails of your cage, nor, having broken them down, to vent your spleen upon this mule of ours. And it was not for you’ (he addressed the mule), ‘to seek this rough-and-tumble nor to scream with such unholy lust for battle. I will have no more of it, my friends! Let this be trouble enough. What, after all, have you done for me? Very little, if anything. But I – I have fed you on fruit and onions, scraped your backs with bill-hooks, cleaned out your cages with pearl-handled spades, and kept you safe from the carnivores and the bow-legged eagle. O, the ingratitude! Unregenerate and vile! So you broke loose on me, did you – and

reverted

!’

The two beasts began to shuffle to and fro, one on its hassock-sized pads and the other on its horny hooves.

‘Back to your cages with you! Or by the yellow light in your wicked eyes I will have you shaved and salted.’ He pointed to the archway through which they had fought their way into the courtyard – an archway that linked the yard in which they stood to the twelve square acres where animals of all kinds paced their narrow dens or squatted on long branches in the sun.

The camel and the mule lowered their terrible heads and began their way back to the arch, through which they shuffled side by side.

What was going on in those two skulls? Perhaps some kind of pleasure that after so many years of incarceration they had at last been able to vent their ancient malice, and plunge their teeth into the enemy. Perhaps, also, they felt some kind of pleasure in sensing the bitterness they were arousing in the breasts of the other animals.

They stepped out of the tunnel, or long archway, on the southern side, and were at once in full view of at least a score of cages.

The sunlight lay like a gold gauze over the zoo. The bars of the cages were like rods of gold, and the animals and birds were flattened by the bright slanting rays, so that they seemed cut out of coloured cardboard or from the pages of some book of beasts.

Every head was turned towards the wicked pair; heads furred and heads naked; heads with beaks and heads with horns; heads with scales and heads with plumes. They were all turned, and being so, made not the slightest movement.

But the camel and the mule were anything but embarrassed. They had tasted freedom and they had tasted blood, and it was with a quite indescribable arrogance that they swaggered towards the cages, their thick, blue lips curled back over their disgusting teeth; their nostrils dilated and their eyes yellow with pride.

If hatred could have killed them they would have expired a hundred times on the way to their cages. The silence was like breath held at the ribs.

And then it broke, for a shrill scream pierced the air like a splinter, and the monkey, whose voice it was, shook the bars of its cage with hands and feet in an access of jealousy so that the iron rattled as the scream went on and on and on, while other voices joined it and reverberated through the prisons so that every kind of animal became a part of bedlam.

The tropics burned and broke in ancient loins. Phantom lianas sagged and dripped with poison. The jungle howled and every howl howled back.

Titus followed a group of servants through the archway and into the open on the other side where the din became all but unbearable.

Not fifty feet from where he stood was Muzzlehatch astride a mottled stag, a creature as powerful and gaunt as its rider. He was grasping the beast’s antlers in one hand, and with the other he was gesticulating to some men who were already, under his guidance, beginning to mend the buckled cages, at the back of which sat the miscreants licking their wounds and grinning horribly.

Very gradually the noise subsided and Muzzlehatch, turning from the scene, saw Titus, and with a peremptory gesture beckoned him. But Titus, who had been about to greet the intellectual ruffian who sat astride the stag like some ravaged god, stayed where he was, for he saw no reason why he should obey, like a dog to the whistle.

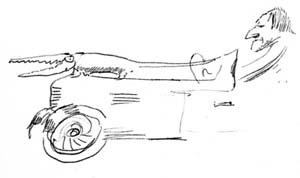

Seeing how the young vagrant made no response Muzzlehatch grinned, and turning the stag about he made to pass his guest as though he were not there, when Titus, remembering how his host-of-one-night had saved him from capture and had fed him and slept him, lifted his hand as though to halt the stag. Staring at the stag-rider, Titus realized that he had never really seen that face before, for he was no longer tired nor were his eyes blurred, and the head had come into a startling focus – a focus that seemed to enlarge rather than contract, a head of great scale with its crop of black hair, its nose like a rudder, and its eyes all broken up with little flecks and lights, like diamonds or fractured glass, and its mouth, wide, tough, lipless, almost blasphemously mobile, for no one with such a mouth could pray aloud to any god at all, for the mouth was wrong for prayer. This head was like a challenge or a threat to all decent citizens.

Titus was about to thank this Muzzlehatch, but on gazing at the craggy face he saw that his thanks would find no answer, and it was Muzzlehatch himself who volunteered the information that he considered Titus to be a soft and rancid egg if he imagined that he, Muzzlehatch, had ever lifted a finger to help anyone in his life, let alone a bunch of rags out of the river.