The Illustrated Gormenghast Trilogy (176 page)

Read The Illustrated Gormenghast Trilogy Online

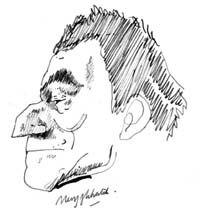

Authors: Mervyn Peake

Around him, tier upon tier (for the centre of the arena was appreciably lower than the margin, and there was about the place almost the feeling of a dark circus) were standing or were seated the failures of earth. The beggars, the harlots, the cheats, the refugees, the scatterlings, the wasters, the loafers, the bohemians, the black sheep, the chaff, the poets, the riff-raff, the small fry, the misfits, the conversationalists, the human oysters, the vermin, the innocent, the snobs and the men of straw, the pariahs, the outcasts, rag-pickers, the rascals, the rakehells, the fallen angels, the sad-dogs, the castaways, the prodigals, the defaulters, the dreamers and the scum of the earth.

Not one of the great conclave of the displaced had ever seen Titus before. Each one supposed this ignorance of the young man to be peculiar to himself, for the population was so dense and so far-flung.

As for Veil, there were many who knew his face: they recognized that horrible spidery walk; that bullet head; that lipless mouth. There was about him something indestructible; as though his body were made of a substance that did not understand the sensation of pain.

As he advanced, a hush as palpable as any sound descended and lay thick in the air. Even the most flippant and insensitive of the characters took on another colour. Knowing no reason for the conflict they trembled, nevertheless, to see the distance narrow between the two.

How the news of the impending battle had reached the outlying districts and brought back, almost on the wings of the returning echoes, such a multitude, it is hard to understand. But there was now no part of the Under-River ignorant of the scene.

Head after head in long lines, thick and multitudinous and cohesive as grains of honey-coloured sugar, each grain a face, the audience sat or stood without a movement.

To shift the gaze from any one of the faces was to lose it for ever. It was a delirium of heads: an endless profligacy. There was no end to it. The inventiveness of it was so rapid, various, profluent. Each movement sank away, sank with a smouldering fistfeel of raw plunder: sank into nullity.

And all was lit by the lamps; reflected by the mirrors. A shallow pool of water at the centre of the circle reflected the long cross beams; reflected a paddling rat as it climbed a high slippery prop, reflected the glint of its teeth and the stiffness of its ghastly tail.

Somewhere in the heart of this sat Slingshott. For a little while he had forgotten to be sorry for himself, so vivid was the plight of the youth.

His hands were clasped together in the depths of his pockets as he stared down into the wet ring. Within a few feet (though they had lost sight of one another) crouched Carrow. Biting his knuckles he kept his eyes fixed upon Titus, and wondered what, without a weapon, the youth could do.

Thirty to forty feet away from Carrow and Slingshott stood Sober-Carter, and on the far side of the open space the old couple, Jonah and his ‘squirrel’ grasped one another’s hands.

Crack-Bell, usually so irritatingly cheerful, sat with his shoulders hunched up rather like some kind of cold bird. His face had sagged: his mouth hung open. He clasped his hands, and for all that he had no part in the conflict they were cold and moist, and his pulse uneven.

Crabcalf, imprisoned by his books, had been carried to the arena in his bed. This bed, on being lifted from the floor had disclosed a rectangle of deep and sumptuous dust.

In the silence was the voice of the river, a muted sound, all but inaudible, yet ubiquitous and dangerous as the ocean. It was not so much a sound as a warning of the world above.

Titus had come to a halt in the centre of the ‘ring’, and had then turned his face to his foe, the execrable Veil. He had little hope, for the man appeared to be composed of nothing but bone and whipcord, and he remembered how quick had been the creature’s recovery from the stomach-jab. It was not just that Titus was frightened: he was also awed by what he saw approaching; this Thing of scarecrow proportions: this Thing that seemed larger than life.

It was as though he were faced with a machine: something without a nervous system, heart, kidney, or any other vulnerable organ.

His clothes were black and clung to him as though they were wet, and this accentuated the length of his bones. About his skeleton waist he wore a wide leather belt; the brass of the buckle twinkled in the firelight.

As he drew close to Titus, the boy saw that he had contracted his mouth so that his lips, which were thin enough on their own account, were now no more than a thread of bloodless cotton. This in its turn had tightened the skin above, so that the cheekbones stood out like small rocks. The eyes glinted from between the eyelids, and the effect was that of a concentration fierce enough to argue insanity.

For a moment only, this concentration slackened, and in that moment he swept his eyes across the terraced hordes: but there was no sign of Black Rose. As he returned his gaze to Titus he lifted his face and saw the great beams that swept across the dim and upper air: he saw the high props, green and slimy with moss, and as his eyes travelled down the rotting pillar he saw the rat.

Now, with a corner of his gaze fixed upon Titus, and with the rat in the tail of his other eye, the spiderman moved unexpectedly, and with a sidling motion, to the left, until he was within reaching distance of the sweating pillar.

A kind of indrawn gasp of relief came from the surrounding audience. Any unforeseen action was preferable to the ineluctable drawing together of the incongruous pair.

But this relief was short lived, for something worse than the horror of the silence brought every one of them to his feet, as with a movement too quick to follow, like the flick of a cobra’s tongue, or the spurt of a squid’s tentacle, Veil shot out his long left arm and plucked the crouching rat from where it lurked, and crunched with his long fingers the life out of the creature. There had been a scream and then a silence more terrible, for Veil had turned upon Titus.

‘And now, you,’ he said.

As Titus bent down to be sick, Veil tossed the dead animal in his direction. It fell a few paces from him with a thud. Without knowing what he was doing Titus, in a fever of fear and hatred, tore away a piece of his own shirt, folded it, and dropping on to his knees, spread it over the lifeless rodent.

Then as he knelt, he saw a shadow move and he jumped back with a cry for Veil was all but upon him. Not only this but there was a knife in his hand.

Black Rose on the far side of the ring had seen the flash of Veil’s knife. She knew he kept it whetted like a razor. She saw that the young man had no weapon, and gathering her strength together she cried out, ‘Give him your knives … your knives! The beast will kill him.’

As though the assemblage had come out of some nightmare or trance, a hundred hands slid into a hundred belts and then for a dozen seconds the air was alight with steel, the great place echoing with the clang of metal and stone. Weapons of all kinds lay scattered like stars across the floor. Some on dry ground, and some gleaming in the pools of water.

But there was one, a long, slender weapon, halfway between a knife and a sword, which, because it hurtled past Titus’ head and fell with a splash some distance from Veil, forced him immediately into action. Turning, he ran to where it lay, and as he plucked it out of the shallow water, he gave a great laugh, not of joy, but of relief that he could hold something tight in his grasp, something with an edge, something fiercer, keener and more deadly than his bare hands.

Two-handed at the hilt he held it before him like a brand. The water was over his ankles, and to the minutest detail he was mirrored upside down.

Now that Veil was so close to Titus that a mere ten feet divided them it might have been thought that someone out of the great assembly would have raced to the young man’s rescue. But not a finger stirred. The brigands no less than the weaklings stared at the scene in a kind of universal trance. They watched but they could not move.

The mantis-man drew closer, and as he did so, Titus drew back a pace. He was shaking with fear. Veil’s face seemed to expose itself as though it were vile as a sore: it swam before his eyes like the shiftings of the grey slime of the pit. It was indecent. Indecent not for reason of its ugliness, or even the cruelty that was part of it, but in the way that it was a perpetual reminder of death.

For an instant there rushed through Titus’ mind an understanding. For a moment he lost his hatred. He abhorred nothing. The man had been born with his bones and his bowels. He could not help them. He had been born with a skull so shaped that only evil could inhabit it.

But the thought flashed and fell away for Titus had no time for anything but to remain alive.

What is it threads the inflamed brain of the one-time killer? Fear? No, not so much as would fill the socket of a fly’s eye. Remorse? He has never heard of it. It is loyalty that fills him, as he lifts his long right arm. Loyalty to the child, the long scab-legged child, who tore the wings off sparrows long ago. Loyalty to his aloneness. Loyalty to his own evil, for only through this evil has he climbed the foul stairways to the lofts of hell. Had he wished to do so, he could never have withdrawn from the conflict, for to do so would have been to have denied Satan the suzerainty of pain.

Titus had lifted his sword high in the air, and at that instant, his enemy slung his blade in the direction of the youth. It ran through the air with the speed of a stone from a sling and struck Titus’ sword immediately below the handle, and sent it hurtling from his grasp.

The force of this had Titus on his back. It was as though he himself had been struck. His arms and empty hands shook and buzzed with the shock.

As he lay there he saw two things. The first thing he saw was that Veil had picked up a couple of knives from the wet ground, and was coming towards him, his neck and head craned forward, like a hen’s when it runs for food, his dagger’d fists uplifted to the level of his ears. For a moment as Titus gazed spellbound the mean mouth opened and the purplish tongue sped from one corner to the other. Titus stared, all initiative, all power drained out of him, but even as he lay sprawling helplessly something moved in the tail of his eye, something above his head so that for an involuntary second he found himself staring wide-lidded at a long slippery beam, a beam that seemed to float across the semi-darkness.

But what Titus saw, and what set his pulses racing, was not the beam itself, but something that crawled along it: something massive yet absolutely silent: something that moved inexorably forward inch by inch. What it was he could not quite make out. All he could tell was that it was heavy, agile and alive.

But Mr Veil, the breaker of lives, observing how Titus had, for a fraction of a second, lifted his eyes to the shadows above, stopped for a moment his advance upon the spreadeagled youth and turned his face to the rafters. What he saw at that moment was something that brought forth from the very entrails of the vast audience, an intake of terrified breath, for the figure, huge it seemed in that wavering light, rose to its feet upon the beam, and a moment later leaped into space.

There was no computing the weight and speed of Muzzlehatch as he crushed the ‘Mantis’ to the slippery ground. The victim’s face had been lifted so that the jaw, the clavicles, the shoulder blades and five ribs were the first to go down like dead sticks in a storm.

And yet he made no sound, this devil, this ‘Mantis’, this Mr Veil. Crushed and prostrate, he rose again, and to Titus’ horror it seemed as though the features of his face had all changed places.

It could also be seen that there was damage to his limbs. In trying to move away he was forced to trail a broken leg which followed him like something tied to his hip: a length of driftwood. All he could do was to hop away from Muzzlehatch with that assortment of features clustered upon his neck like a horrible nest.

But he did not go far. Titus, Muzzlehatch and the great awestruck audience realized suddenly that the knives were still in his hands, and that his hands and arms alone had escaped the destruction. There, in his fists, they sparkled.

But he could no longer see his enemies. His face had capsized. Yet his brain had not been damaged.

‘Black Rose!’ he cried into the dreadful silence. ‘Take your last look at me,’ and he plunged the two knives, through the ribs, in the region of his heart. He left them there, withdrawing his hands from the hilts.