The Imaginary Lives of Mechanical Men (24 page)

“Yes, retired actually. Or, rather, semiretired, I suppose you should say.” He spoke in single words and phrases, like a man who has spent the last of his energy in an uphill race. “You know, I have a great-granddaughter, Miss Meyer, whom I haven’t seen. In five years. I doubt she would recognize me with the perspicacity that seems to be your defining trait. There. I believe I have completed an entire thought. Without interruption.”

“Judge Burrelle, if you’ve come here about …”

“Please. This will take a few moments, but I thought I should do this one in person since it involved one of my own cases. Seems the right thing, don’t you agree, when one is contemplating how close he is to final judgment himself. Yes. Yes, I hadn’t thought of that, consciously, until just now. One wants to do. Whatever one can.”

He went on to explain that he had retired two years after hearing my case. His wife had died, and so had the partners in his old firm. And the idea of making new friends, at his age, seemed as repellent as learning how to eat new food. As he talked, I began to watch his hands the way I would have watched the hands of a child. They seemed to be more expressive than his words, cleaning his glasses with the pocket handkerchief, adjusting the fastidiously tied bow tie, checking, one by one, the buttons of his vest to make sure he had not missed a hole. I could imagine him in the first years of his emptiness learning how to tie flies, sitting up late at night in his study, peering through a magnifying glass as he twisted feathers and fur and fishing line into fantastic shapes that disguised the hook. Then lifting each one with

tiny tweezers, inspecting it in the light of a goosenecked lamp. That was the way I imagined him, and it was, in a sense, the message he had come to deliver.

“After a few years,” he said, “I found I couldn’t stand the void, being locked in my own house twenty-four hours a day. And of course with the constant backlog of cases, tort reform, legislative review—they’re glad to see anything in a black robe. So. Here I am, Miss Meyer. Here. I am.”

“I’m afraid I don’t understand.”

“Yes. I suppose you don’t. Let me ask you something first. Are you married, Miss Meyer? Is that still your name? Because this,” he made a peculiar gesture with his hand, as if introducing himself to an unfamiliar audience, “is still the address of record for your case, and it’s not a house at all. It’s a bookstore that used to be a house, with some of the walls removed and shelves put in. And books. And china and silver in display cases over there. And exotic lamps. And very fine paintings for sale and very old magazines that are not. All of this inside the shell of a house sitting beside other houses on a street that is not a commercial street. And so I naturally wonder if I am in the right place. For the right reasons. Do you have children, Miss Meyer?”

“What do you want?”

“I’m part of a three-judge panel now, a sort of review board, examining old cases. Writing recommendations for the Judiciary Committee. Correcting a few old mistakes. I hope that doesn’t shock you as profoundly as it shocks us. Three old fellows of the bar, occasionally stumbling over one of their own mistakes.”

“What do you want?”

“The picture of course. That’s the best I can do.”

“The best that you can do?”

“Yes. We all agreed. It was a mistake. Far outside the sentencing guidelines, even ten or twelve years ago. The newspapers loved it of course. There were clippings. But poetic justice isn’t justice, and it was in fact a mistake. That’s the reason I’ve come myself. To tell you that

your sentence, the terms of your probation, have been reviewed and set aside. Officially.” He took a long envelope from the inner pocket of his coat and passed it to me.

For a long time I said nothing. Did not open the envelope or even touch it where it lay.

I looked at it and wondered what he expected me to do.

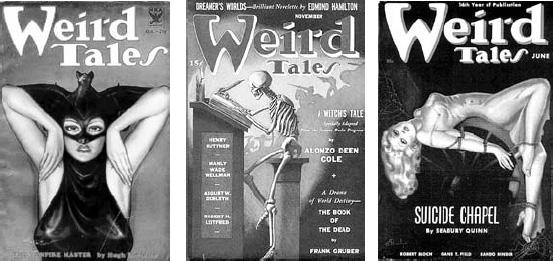

Weird Tales

, October 1933, Volume 22, Number 4.

$625. Cover illustration by Margaret Brundage. Lead story “The Vampire Master” by Hugh Davidson, a novel, part one of four. Overall VG to Fine condition. Cover background lime green to forest green to dark green, mottled (in orig. illus.) but no fading. No splits or tears. All pages intact. No flaking or chipping. No tape. No marks. Purchased at auction.

This is the famous “bat girl” cover by Brundage.

I keep it in the cabinet beside the display case because it is so rare.

She is dressed in black and wearing a mask that covers the upper half of her face. Some collectors have suggested that it is a Halloween mask because the cover was published in October, but I believe it is more than a mask. It is a crown or a helmet, fitting over the skull like a second skin and spreading itself at the top into the image of a bat, its outstretched wings suggesting a hovering menace like the hooded cobra of a pharaoh’s crown. And the subtle decadence of the dress she wears, high collared and tight around the throat, shining like black satin and straining against her breasts, is as detailed as decadence could be in 1933. Sometimes the collectors come into my shop and ask for the one with the girl in the leather dress or the hooded halter, you know, the one with the arms like this.

And that is what they want, the arms in a most peculiar pose. Raised, elbows high, with forearms angled down, almost into an inverted V, so that the backs of her hands lightly touch her face. Which suggests, somehow, a world of sensuous flesh. They see it too in her mouth, the lips parted and curved like an unbent bow, innocent of any smile. And the eyes, of course, as black and vacant as the abyss. Has she been

caught, we want to know, in a moment of drunken lassitude; or could we see, somewhere off the sheet, that she has been pinned like an exotic moth against the green velvet, dying by degrees, like one of Scott Fitzgerald’s tubercular wives.

They all know that any cover by Margaret Brundage is valuable. The sylph-like girls on every one of them are uncomfortably real and fragile, giving the impression of having been drawn from living models. Indeed, it’s surprising that she became the most collected artist of the pulp era given the fantastic excesses of her competitors. Her own covers have little depth or background, and her lines, having been first set down in pastels, did not translate well to print, especially considering the primitive technology of the time. In style they resemble the drawings found in fashion magazines. Often there would be only a single detail separating Brundage’s world from that of

Harper’s Bazaar

—a ballerina dancing with a severed skull, a harem girl with a whip. From 1929 until 1938 she was the only female artist in the world producing art for the pulp market, and yet during those years she had a virtual monopoly on the covers for

Weird Tales

. Today they are called fetish covers and are collected by people who have never read the stories of Lovecraft or Howard, Clark Ashton Smith or Seabury Quinn. They are now what they were then, splashes of color in monochromatic lives, frail treasures in red and green, and black and gold, and yellow and blue.

In the future.

We will go looking for the rocket cars in red and green, skimming from dome to dome. Which one is our city? That is what we will want to know. And our elevator to Mars? Where are the autopilots and happy passengers? And where have we berthed the space yachts with their light sails billowing like

Cutty Sark

and their teenagers racing around the sun? The gyrocopter in the garage and the robot dog at night? Where did they go? We have been promised for decades our floating house with foam furniture and never-aging skin, or at least a

cream to set the wrinkles right. Picnics on some Sea of Tranquility with our rocket engineer and our android child, plucking meteors like peaches. Reminiscing of Earth our home. They seem to have all gone missing. Every storied issue of “Life in the Year 2000” has been confiscated, lost, compacted with the trash of the last millennium. And we’re on our own.

That’s why I have my shop. I lay the covers out like this because they send the only signal that I know. I try to show them with “The Black God’s Kiss” that she’d willingly embrace, set her mouth to cold obsidian and insinuate her hips beneath the folds of his darkened robe. But no. It’s a still life after all. His eyes are hooded hawks, and in his squatting pose the graceless hands grasp only at his graceless feet. It’s a statue and not a god. While her insistent curvature shouts, “Look at me, the pretty one. Look at me. Perfectly preserved. In glass.”

In other words, I give them the perfect truth, that nothing ever happens on our covers. The sword is raised but forever stayed. Beauty really rendered into art within some frozen vat. Because the story is ever undercover, and in between the words of brittle pages. We do not thumb them, I have found, when we know they will flutter to the floor.

So I wait for some pioneer to break the mold, some intergalactic ranger perhaps, who will slip between dimensions and find my little shop. Sometimes they do, making furtive visits before their energy abates, lingering like a man looking for the lost jewels of … some childish, imaginary place. And maybe once a year the boldest one will ask, “Are you the one? Who collected all of these? Because the sign outside …”

“Doesn’t list my name,” I will say.

And then he will fumble, adding, “Oh yeah. What I mean is, someone gave me your card. And I was wondering …”

Or perhaps he will explore. Buy a few titles from the mundane

shelves, the ones that keep me in bread and milk, making himself familiar with the territory, before drifting into the happy aisles. Twisting his wedding band the way they do, looking up and down to make sure we are alone before suggesting, “Are you the one? Who collected all of these? Because the sign outside …”

“Doesn’t list my name.”

“Doesn’t list your name,” this special one will say. But I can sense the need behind his wooden words. It’s maybe once a year, or maybe once in every two, when one of them will take the extra step. “Though it’s just … such a great name for a bookstore. Why, when I was a kid, I could spend days in a place like this.”

And “Pulp Life?” I will say. “You like my name? Well, thank you. You’re very kind to notice.”

“Yeah. Someone gave me your card, you know, told me about this place. And I was wondering. Do you have some more? Some items, I mean, that you might not have out here. To build a collection around.”

It’s the moment that I encourage him, step close enough to study the brown hair flecked with gray and brown eyes set beneath a wide, intelligent brow, like one of those descriptions in Edgar Allan Poe. And even if it’s summer, he will wear his tie, carry his sports coat over the sleeve of his blue-checked shirt. And probably I will think he is English because his diction will be so precise and because he’s one of the gentle ones determined not to show his wounds. With an aura of expensive aftershave. A slight fraying at the cuffs. “What do you have in mind?”

And he will say, “I’m not sure, in fact. I thought I just might look. If you had some more like these. It seems like I’m recapturing part of my sordid past.” And he will laugh an awkward laugh.

“Yes. A few. Back here,” and I will laugh as well, touching his arm like this to show a slight embarrassment, “in the back bedroom.” But of course there will be tables and shelves as well as lamps and chairs. All completely safe. And if, at the end of the afternoon, we have found

what we both will need, then we sit in silent union for maybe an hour more. Turning pages that crumble as we read. Mouthing words that keep us home to stay.

ONE WHO GOT AWAY

Escape

FOR IAN

1

It’s so steep at the crest that Rifken can simply lean forward, and the snow holds, as pliable and comforting as a blanket. He works a hollow among the boulders and waits, drinking in the thin air. There are no tree limbs between him and the white moon. And there is no more to the mountain, no higher ridge to supply perspective. There is just the momentary illusion that he is back at his grandfather’s farm, looking down upon a floating disk at the bottom of a stone well. The only movement comes from Hargadon, the younger deputy, thirty yards below in the frozen present and still climbing with undiminished energy. It takes the kid several minutes to scramble past and then edge up to the ridge itself, where he takes out binoculars and tries to read their future.

“If you’re going to do that,” murmurs Rifken, “may as well stand up and wave a flag.”

Wind rakes powder from their ledge and scatters it over the valley. Hargadon hunches lower, crabbing backward onto a shallow shelf made by his feet. “It’s still dark,” he says. “He couldn’t have seen me.”

“There’s a moon. And there’s snow.”

“Hell, I don’t know. I don’t even know what day it is anymore. It’s so damn cold I can’t feel a thing. I can’t even think.” Hargadon slips off

a mitten to cup his bare hand over nose and mouth, puffing four, five breaths while the vapor rises between his fingers.

“He’s down there, isn’t he?” Rifken tries to see in his mind what’s on the other side of the ridge.