The Incredible Human Journey (23 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

So, had the earliest Australians killed off these ancient beasts? It seems that humans and megafauna may have co-existed in Australia for 10,000 years, if not more. Some researchers think that the megafauna were hunted to extinction – although there are no megafauna kill-sites to support this argument. Others have suggested that climate change was the real killer, with the cold dryness of the LGM finishing off the huge Pleistocene animals of Australia. But recent dating of fossil megafauna suggests that many species of megafauna became extinct across Australia between 40,000 and 50,000 years ago – at least 20,000 years before the LGM. So these dates do suggest that humans might have had something to do with it, either killing off the giant beasts directly or else by disrupting the ecosystem in some way.

2

Some archaeologists believe that there is another indication of human impact on the environment at just this time, with a decline in forest starting around 45,000 years ago, linked to burning of large areas,

3

,

4

but it’s impossible to know if it was people who started the fires.

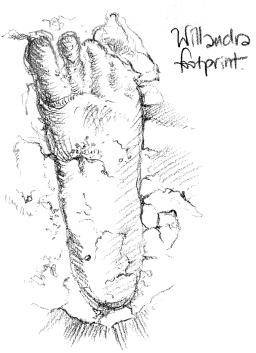

The next day we set off again and ventured on to even rougher tracks, winding through the bush until we reached the site where the archaeologists had converged. They had come on a conservation mission: to check the preservation of the Willandra footprints. And these were very precious footprints: they were around 20,000 years old. Several Aboriginal elders were there at the site as well, overseeing the operation. Some of the younger archaeologists were themselves Aboriginal people, trained to recognise archaeological features in the landscape and to look after their own heritage. The footprints themselves were found, in 2003, by a young Aboriginal woman, on an archaeological training day. Steve Webb, an anthropologist from Bond University in Robina, Queensland, had been taking a group of trainees on a field-walking exercise, teaching them how to recognise ancient artefacts and features. They had actually ended up in the wrong area, but Webb had decided it was as good a place as any just to do some training. Then one young woman, twenty-six-year-old Mary Pappin Junior, spotted a footprint. Webb realised that this couldn’t have been a recent footprint: it had been buried under sediments, and revealed by the wind blowing away the sand over a much harder surface. And there were more: in all, eighty-nine footprints had already been revealed by natural erosion.

When the site was excavated, more footprints were found: 563 of them, over an area of 850m

2

.

5

The prints were preserved in a layer of very hard, silty clay. When they were made, the clay must have been moist, perhaps soon after rain. Then it dried hard before being covered by windblown sand. Twenty thousand years later, the wind was undoing its work and revealing these usually ephemeral traces. But the same wind was also threatening to destroy the exposed prints, literally sand-blasting them away.

‘Once the site was excavated and exposed to elements, it almost immediately started to deteriorate,’ Michael told me. ‘First it was sandblasted by the wind, and then it suffered a nasty freeze-thaw event. We watched the footprints change before our eyes – over just a few months.’

The archaeologists had to come up with a plan to preserve the precious trackways; they decided to cover the prints back up, with 65 tonnes of sand, pinning a fabric membrane over the surface of the sand to stop it blowing away. But before they did this, they made a record, by digitally scanning the whole site.

The archaeologists had come back to assess how well the conservation plan was working, and I was extraordinarily lucky to be visiting the site when this health check of the footprints was being carried out. In any other week of 2008 I would have seen only the membrane covering the site. But there I was, watching the archaeologists cutting neat holes in that protective fabric and carefully digging and sweeping out the sand from a few chosen footprints.

‘We’re reopening just a few of the prints to see if the weight of that sand is distorting the footprints,’ said Michael. The re-exposed footprints certainly looked good to me: the toes were clearly defined, and you could even see where the muddy clay had squelched up between them.

I had seen some ancient footprints before, on the coast of Formby in north-east England, but these Australian prints were much, much older. Footprints can be very useful from an archaeological, anthropological point of view. The very ancient footprints from Laetoli in Tanzania have been useful in reconstructing the way australopithecines walked – and indeed, prove that they

did

walk on two legs.

Footprints of early modern humans tell us where people were, and a little about past societies and social behaviour. But I actually think most of the ‘scientific’ information to be gleaned from them is fairly obvious stuff: people in the past (including children) walked or ran, in straight or curving lines. You can work out stature, too. Not exactly mind-blowing. Although, rather strangely, there is one rather intriguing trackway at Willandra that appears to be that of a one-legged man – moving at some speed!

But, to my mind, the footprints do something more than just provide us with data: they link us back to long-forgotten people in a very personal way. They are records of a brief moment in someone’s life. There is something quite profound about looking at something which is usually such a fleeting sign of another human’s presence, and knowing, without a shadow of a doubt, that a person walked just

there

, where you are standing, all those thousands of years ago.

So how, you may be asking, did those archaeologists manage to date those footprints? The answer: OSL. By taking samples from the sediment just under and just above the footprints, and using optically stimulated luminescence to measure the amount of time that quartz grains had been buried for, an age range could be determined. The footprints had been made some time between 19,000 and 23,000 years ago.

1

So what had those prehistoric Aboriginal people been doing there? It looks like there was a group of people, of different ages, moving around the margins of the lake, and precisely what they were up to as they made those footprints we can only guess. But we do know that, at the time, the lakes would have been a good place for hunter-gatherers to hang out, with plenty of fish, shellfish, waterbirds and game to hunt.

1

But it was a rare combination of factors that meant that their footprints had lasted until the present.

‘We don’t find footprints all over Australia, and the preservation of the footprints here is still a bit of a mystery – but there would seem to be a couple of favourable factors here,’ explained Michael. ‘One factor is the clay itself: it contains a mineral called magnesite, which is fairly rare, and seems to help mould the footprints perfectly. And the clay must have been wet when the people walked across it. Then, soon after, windblown sand covered the footprints over – and locked them in for some twenty thousand years.’

For Michael and the other archaeologists who had come up with the conservation plan, it was looking very reassuring. On site, they were able to compare the re-exposed footprints with photographs from the original excavations. It looked like very little deterioration had occurred: the sand and membrane were definitely doing their job. They had also brought along a laser scanner to take detailed scans of the footprints, to compare with scans taken when the prints were first exposed. Once each of the six or seven exposed footprints had been scrutinised, photographed and scanned, they were carefully covered up again with sand, and the membrane drawn back over and secured with cable ties.

There is other, more ancient evidence of humans living around those lakes. In fact, Willandra Lakes were famous long before the footprints were discovered. In 1968, the remains of a cremated skeleton were found, eroding out of the dunes that fringe Lake Mungo. Geologist Jim Bowler and his colleagues had been collecting shells and stone tools from the Walls of China, and had found a collection of burnt bone fragments that he first thought were the remains of some early Australian’s dinner. But, on further inspection, it looked like the bones could in fact be human.

The archaeologists had been expecting to work on surface finds and now they had an excavation on their hands. They collected up the loose pieces of bone, then removed a block containing bones which had been naturally cemented together with calcium carbonate or calcrete. The specimens were carried off site in a suitcase.

In the lab, anthropologist Alan Thorne carefully removed the calcrete from the bones using a dental drill; they were definitely human. The fragments represented the remains of two individuals, named, rather predictably, ‘Mungo I’ and ‘Mungo II’. Number two consisted of just a few fragments. Mungo I was also fragmentary, but there were enough pieces – about 25 per cent of a skeleton – to be able to tell that these were the cremated remains of a lightly built young woman. The skull was fragmentary, but what was there looked similar in many ways to modern Aboriginal Australians.

Careful analysis of the bones provided some insight into the funerary ritual. The body had been burnt while still complete, but the bones of the spine and the back of the head had largely escaped the flames of the pyre. After the cremation, the bones had been smashed up, a funerary practice which was still happening in Australia and Tasmania until quite recently. The bone fragments had then been scooped into a shallow pit at the lakeside. Initial radiocarbon dating of shells associated with the cremation suggested it could be around 30,000 years old: the oldest human remains to be found in Australia at that time.

6

Alongside the cremation, the archaeologists found stone tools, animal bones and hearths, which provided important clues about the lifestyle of ‘Mungo Lady’ and her people. They ate a varied diet, catching golden perch in the lake and eating shellfish collected from its margins. They also ate emu eggs, small birds and bush meat. The archaeologists examining the clues left on the lake shore decided that the evidence pointed to a few visits to that particular site, by a small group of perhaps one or two dozen people. They suggested that it was a camp that had been used for a few seasons before either being abandoned or getting covered up by sand and mud.

The diet and lifestyle of these ancient Aboriginal people seemed quite similar to that of Aboriginal Australians around the Murray and Darling rivers in the nineteenth century: camping by rivers and lakes in spring and summer, eating fish and shellfish, and moving into the bush in winter, where they would catch and eat a range of marsupials.

6

It seems strange in some ways that this ancient lifestyle persisted in Australia, whereas, in different parts of the world, people settled down and started farming. Whatever pressures there were in other places, to give up that nomadic lifestyle and settle down, it seems they were either absent or were somehow overcome in Australia – without necessitating a major change in subsistence strategy.

Six years after the discovery of Mungo Lady, Jim Bowler found another burial in the dunes. A few days later, Jim Bowler and Alan Thorne excavated the burial. This time, the body had been buried, with the hands clasped over the pelvis, and covered in ochre. Its position in the dune again suggested that the burial was about 30,000 years old. This skeleton, Mungo III, was described as being lightly built, but nonetheless male, and was quickly dubbed ‘Mungo Man’.

In 1999, Alan Thorne had another go at dating Mungo Man, this time using ESR and uranium series techniques on the skeleton itself, as well as OSL on sand grains from sediment below the burial. All the results were much older than the previously published dates for Mungo Man. It looked as if the burial could be over 60,000 years old.

7

This was an incredible date: it would make Mungo Man the oldest known modern human outside Africa.

Jim Bowler was not convinced by this very early date, and published a paper saying so, entitled: ‘Redating Australia’s oldest remains: a sceptic’s view’.

8

He called into question the methods that Thorne had used. He wrote that Alan Thorne had made erroneous assumptions about the composition and erosion of the sediments that Mungo Man had been buried in, which made his ESR and uranium series dates untenable. And he didn’t mince his words when he came to the OSL dates, which Alan Thorne had obtained from samples of sediment not directly next to the skeleton, but from about 400m away.

A few years later, Jim Bowler and a team of scientists published some new dates for Mungo Man and Mungo Lady. Samples of sediment from the burial sites were sent to four different labs for OSL dating, and all came back with dates of around 40,000 years ago.

9

These were older than the original radiocarbon dates, but much more believable than the dates published by Thorne’s team. Mungo Man and Lady were still the most ancient Australians known.

Even when I got to Mungo, I wasn’t sure if I was actually going to be able to see the human remains. Ancient skeletons have become symbols of identity for modern Aboriginal people, who feel – and understandably so – that their own heritage and beliefs have been largely disregarded, even trodden underfoot, in the recent past. Colonialism has a lot to answer for. As some attempt to redress the balance, the official policy in Australia was now that prehistoric human remains, however old, should be returned to communities of indigenous people,

10

but the implementation of this policy could be quite difficult – but perhaps not for obvious reasons.