The Incredible Human Journey (43 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

Clive didn’t like the idea of Gibraltar as a ‘refugium’ for Neanderthals. ‘When we talk about a “refuge”, the impression is almost that this is a place that Neanderthals came because there was nowhere

else to go,’ he said. ‘The reality is that this was a good place to be. And for a period of 100,000 years, there were Neanderthals

living here.’

Even when Europe was beginning to feel the full chill of the LGM, between 28,000 and 24,000 years ago, south-west Iberia was

experiencing a mild but still balmy Mediterranean climate, with mean annual temperatures of around 13–17 degrees C – in fact,

very similar to today.

3

,

4

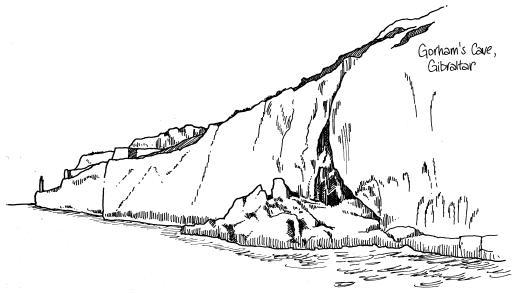

The large caves that now lie right on the rocky coast would have been set back from the seashore 25,000 years ago. Offering

protection from the elements and from predators, I imagined the caves would have made quite sought-after Palaeolithic homes.

Hearths had been lit deep inside Gorham’s Cave – but it was tall enough for smoke to rise to the ceiling and find its way

out without getting into the eyes and throats of the cave-dwellers. And there were plenty of resources just on the doorstep. The sea would have been much lower than it is today, with a mosaic of habitats including woodlands and wetlands between the

foot of the cliffs and the coast. The sandy coastal plain would have been dotted with sand pines and junipers, and liberally

watered with streams. ‘The vegetation also indicates seasonal pools,’ explained Clive, ‘and that’s also borne out by animal

remains that we’ve found, including newts and frogs, and waterfowl like ducks and coots.’

We had hoped to access the cave from the sea, but just an hour or so after we had set out on a millpond, the winds and currents

had conspired to create a sizeable swell that would make any landing attempt dangerous. We continued northwards in the boat, Clive pointing out other caves that had been home to Neanderthals. But, of course, with

the change in sea level, it was likely that a lot of evidence was under the waves. And Clive and Gerry were looking there,

too.

Turning around, we headed back around Europa Point and into the Bay of Gibraltar, to rendezvous with the dive boat. Already

on board were Gerry and marine ecologist Darren Fa. As we transferred on to the boat, I learnt that work had already started:

somewhere beneath us, two underwater archaeologists were busy trying to move a large rock, using air-filled lift bags. Gerry

was hoping that removing this rock would reveal an undisturbed layer of sediment. Surveys of the seabed had revealed a large

reef, some 20 to 40m beneath the waves. Caves in this reef would have been on the coast – rather than underwater – during

the time of the Neanderthals. The archaeologists were interested in collecting samples which would provide even more information

about the palaeoenvironment, but they were also hoping that they might find signs of ancient occupation hidden beneath the

seabed. Mounting an archaeological investigation of this type requires expertise in diving, marine ecology, underwater archaeology

– and patience.

‘The logistics involved are really difficult,’ said Gerry. ‘It’s expensive and very time-consuming. If you’re excavating

in a cave and your pencil breaks, for example, you can just go to your box of tools and get another one. If you’re on the

bottom of the sea and your pencil goes, and you don’t have another, that’s the end of your dive. We take two of as many things

as possible. We plan very carefully. But sometimes things go wrong, and you have to come back to the surface.’

Each diver could stay down for only an hour at most – so each day’s digging was about meticulous planning, and small but effective steps towards collecting data. They worked in shifts; Gerry and Darren got into their wetsuits and dive gear ready

to step in as the first team resurfaced.

Out on the boat, I could clearly see the mountains of Morocco in the distance: the Rock of Gibraltar lies just 21km across

that narrow strait from Morocco. Once again, I found myself surprised that there was no evidence that this had ever been a

crossing point in Palaeolithic times. Modern humans appeared to have stayed firmly put on the African side, and there’s nothing to suggest that Neanderthals ever

made the journey over to Morocco either.

When Gerry and Darren came back up, I asked them what they’d found.

‘We actually managed to move the rock using the lift bags,’ said Darren. ‘And we got some sediment,’ said Gerry. She was very

pleased that they had made steady progress and managed to safely shift the rock, opening up the previously covered sediments

for excavation. I had sort of hoped that one of the divers might bring up a nice Mousterian tool from the seabed on the day

I was there, but that was a bit too much to hope for. It was slow and painstaking work – but essential if we are to learn

more about the ancient environments that our ancestors and Neanderthals inhabited.

Back on dry land, Clive was keen to show me some of the animal bones that had been found in Vanguard Cave, the neighbouring

cave to Gorham’s, occupied by Neanderthals over 50,000 years ago.

I picked up a metapodial, a foot bone. It looked a bit like a sheep bone to me. ‘That one,’ said Clive, ‘well, either it’s

their favourite, or it’s easier to catch, or there’s a lot more of them than other herbivores. It’s a wild goat: Iberian ibex.

Eighty per cent of the large mammal bones belong to this species.’

Red deer bones were also fairly common. ‘They were quite partial to those.’ There was also a bone from an aurochs: a massive,

ancestral cow. Clive thought that bringing down an animal of this size, with its huge horns, would have required a certain degree of courage,

planning and cooperative hunting. ‘It’s probably not remarkable that we don’t find that many of them,’ he said.

‘Perhaps surprisingly, given what has been said about Neanderthals, we’re also finding smaller animals. Nearly 90 per cent

of all the mammal bones are rabbit.’

I did find this surprising. It didn’t fit with the traditional view of Neanderthals as big-game hunters.

‘And it’s not just land resources that they’re using,’ said Clive, rather proudly. ‘They’re eating limpets and mussels. And

just look at this,’ he picked up a jaw with sharp teeth. ‘It’s a monk seal. And this isn’t an isolated case. A lot of the

bones have cut marks. I think there’s too many of them to be stranded animals; I think they’re hunting them. And it gets even

more complicated when you look at things like this …’

He handed me a dolphin’s vertebra. I could just make out some cut marks on one of the bony levers – the transverse processes

– sticking out from the body of the bone. These weren’t trowel marks from a clumsy modern archaeologist: they were thin cuts

from a flint tool. It appeared that we were looking at the remains of a Neanderthal’s dinner.

5

So it looked like Neanderthals were just as capable of adapting to a coastal way of life as our ancestors had been. There

were bird bones as well – but could Clive be sure that these had been eaten?

‘There’s very little evidence for other predator action. We don’t have cut marks on these bones, but it seems that there may

be tooth marks – from Neanderthals. The dominant species are partridge, quail, ducks: the kinds of birds that you or I might find palatable. Clearly, birds are on the menu.

‘We’ve looked so much at Neanderthals in the north where large mammals were available, and it’s created a slightly biased

impression,’ suggested Clive. ‘Here, big game was in the diet,’ he continued, ‘but I see the Neanderthals more as beachcombers,

collectors of plants, hunters of birds and rabbits, who occasionally caught a goat, more occasionally a deer, and even more

occasionally got a large, dangerous animal. Like human societies today, I’m sure the Neanderthals had cultural and geographic

diversity. They were exploiting whatever was available on their doorstep.’

Other sites also challenge the idea of the Neanderthals as behaviourally inflexible. Arcy-sur-Cure in south-west France has

produced stone tools that are rather weird – almost sitting on the definitional fence between Middle and Upper Palaeolithic

– combining Mousterian-like flake-based tools with ‘Upper Palaeolithic’ blades and bone tools. While it appeared to have developed

out of the Mousterian tradition, it was seen as marking the beginning of the Upper Palaeolithic in Europe, and used to be

called the ‘Early Aurignacian’. Along with the ‘transitional’ toolkit, there were also pierced fox canines, apparently evidence

of personal ornamentation. The site is not unique: the tools from Arcy are classified as

Chatelperronian

, after the cave at Chatelperron in south-west France where this technology was first described. Examples of this technology

have been discovered throughout central and southern France, and in northern Spain. But who made it? Fossils had been found

in association with Chatelperronian tools at Arcy-sur-Cure, but they were so fragmentary that it seemed impossible to tell

if they came from modern humans or Neanderthals. They dated to 34,000 years ago – when both populations were in Europe.

But then, in 1996, an international team including French archaeologist Jean-Jacques Hublin and Fred Spoor from UCL showed

that the anatomy

inside

the temporal bone – the bone at the side of the skull that contains the workings of the ear including the semicircular canals

– was characteristically Neanderthal.

6

So this suggests that it was Neanderthals who made the Chatelperronian. But did they invent it independently or copy it from

modern humans, or is this a change in technology that shows behavioural adaptation to a changing environment? Clive put it

to me that it represented a change from ambush hunting to projectile technology. It seems pertinent that the Chatelperronian

appears only after modern humans have come into close proximity with Neanderthals – but this was also a time of major climate

upheavals. In fact, both possibilities – copying or innovation – suggest a certain behavioural flexibility and intelligence that we

have not always credited the Neanderthals with in the past. ‘I think we may have underestimated the Neanderthals,’ said Clive.

The Chatelperronian can be seen as rather problematic as it blurs the distinction between what archaeologists would consider

to be a Neanderthal and modern human technologies. It challenges our pre-conceptions. Archaeological evidence like this makes

it seem less inevitable that modern humans survived where Neanderthals didn’t – and shows that the Neanderthals were much

closer to us than we’ve perhaps liked to think in the past. But they did disappear. On a continental scale, climate changes

and the presence of a competitor in the landscape probably played their roles in the demise of our sister species. Their population

gradually contracted, until, it seems, just a few of them were left in Gibraltar, happily living a coastal lifestyle in this

idyllic corner of Europe, and probably completely unaware that they were the last of a long European lineage. So what happened

to the last Neanderthals?

From Clive and Gerry’s work on Gibraltar there doesn’t seem to have been a ‘last stand’ with modern humans taking the Rock

from their distant cousins. There’s a distinct gap between the last evidence of Neanderthals, at 24,000 years ago, and the

first evidence of modern humans – at about 18,000 years ago. ‘There’s a gap of five thousand years when there’s nobody living

in these caves,’ said Clive. So it seems that competition between the two populations could not have played a role in this

particular location.

Clive suggested that, in the end, it may have just been a numbers game. If the Neanderthal population was very small, then

they could have easily died out – just think of threatened species today. ‘These last Neanderthal populations would have been

very small and very vulnerable,’ he said. Inbreeding and increased rates of congenital disease could also have contributed.

But Clive also thought that climate played a crucial role in the demise of those late-surviving Neanderthals. ‘We’ve looked

at deep-sea cores offshore here, and the most severe climatic conditions of the previous quarter of a million years hit precisely

at the point that Neanderthals disappear.’

Although Gibraltar had enjoyed a mild climate up to 24,000 years ago, there then seemed to be a sudden and severe downturn

in conditions. Evidence from marine cores shows a drop in temperatures at this time, known to palaeoclimatologists as the

‘Heinrich 2 Event’. These Heinrich Events are moments of ‘ice-rafting’: icebergs breaking off the northern ice sheets then drifting south in

the Atlantic caused a distinct chill in the ocean. The Neanderthals had survived cold before, but during this ‘event’, the

sea surface temperature was the coldest it had been for a quarter of a million years. For Clive, this sudden cold and dry

period could explain the demise of the last Neanderthals. ‘So it could be that climate change was the final nail in the coffin

for these last Neanderthals.’

For Clive, the

final

extinction of the Neanderthals and the expansion of modern humans are separate events. Though he accepts that contact may

have happened elsewhere, the evidence on Gibraltar shows that those late-surviving Neanderthals disappeared thousands of years

before modern humans arrived on their patch.

3