The Incredible Human Journey (8 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

Then we were back in the air again. The second leg of the journey took us over more wooded hills and valleys. Suddenly, Solomon pointed down at a narrow, shining ribbon: ‘There it is: the Omo River.’

And there it was, meandering southwards through a wide, wooded valley. Then I lost sight of it as we flew up over a ridge of mountains. Solomon handed over the controls of the plane to me, and I followed his directions. ‘Continue straight on down this valley, and the Omo will loop round and meet us again on the other side of those mountains,’ he said, pointing to the edge of a ridge in the distance. I flew for about another half an hour, taking the plane down from 5000 to 3500ft, then Solomon took control again as the river reappeared and we approached our destination. We had passed the mountains, and were now flying over a wide, flat flood plain, with the Omo thrown in wide, brown coils across the landscape. Next to the river, the land was densely forested, breaking up into scrubby bush away from its banks. But it was still greener than I had expected. The flood plain was huge. I wondered

how

Richard Leakey had ever found those fossils.

As we flew lower, I saw a village on a hill looking over a wide arc of the Omo. It was Kolcho, the nearest village to Murule camp, where I would be staying. We circled round and landed at a dusty airstrip where Enku Mulugeta met me in a Land Cruiser. After unloading the plane, Solomon took off again, bound for Addis Ababa; he would return on Friday to pick me up. And I was in the middle of nowhere.

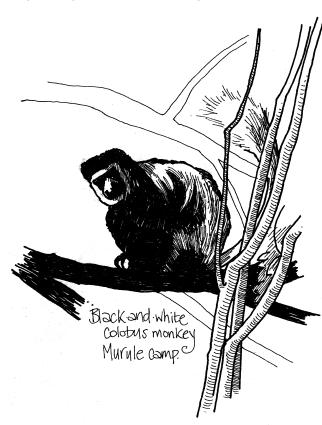

Murule Lodge was situated right on the banks of the Omo, which was wide and greasy-brown here. It was high on its banks and fast-flowing, after recent heavy rains in the mountains. The small houses of the lodge were surrounded by tall trees. Almost as soon as I arrived I heard branches moving above me, then there was a shower of small twigs and leaves. I looked up to see a black and white colobus monkey staring down at me through a forked branch. We made eye contact and then he was away, throwing himself through the trees with amazing speed and agility.

More colobus followed in hot pursuit.

I had been expecting a very basic camp, so my little house at Murule came as a very pleasant surprise. The windows were covered in mosquito screens, with curtains inside and raffia blinds outside. There was a large room in the house, with a double bed, a crude wooden chair and a sill wide enough to hold my bag. A single lightbulb hung in the corner of the room, but there were also pots of sand on both sides of the bed, with candles and matches. (Electricity was an occasional luxury here, powered by a generator for just a couple of hours after sunset.) I even had a bathroom, square and concrete, with a flushing toilet, a sink and a shower fitting in the ceiling. Admittedly, the shower was unheated, untreated water straight out of the Omo, but it was all so much more luxurious than I’d anticipated for this remote place in the middle of the Rift Valley – even if I was sharing the place with a few geckos and a strange-looking spider with a penchant for hiding inside toilet rolls, a ploy destined only to scare the life out of both of us.

I fixed up my mosquito net. It was late afternoon and the mosquitoes were just starting to bite. As night fell, I sat out on a wooden chair looking over the Omo, with a packet meal and a bottle of locally brewed St George beer. I was being extraordinarily careful with food and water here: consuming nothing unless it came out of a packet or a bottle. We were too far away from anywhere to take any risks, and I didn’t want to jeopardise my one chance of visiting the site where the Omo fossils had been found. I turned in around ten; I had an early start the next day, and I knew it was going to be tough.

I slept well that night, despite the sticky heat and the noisy wildlife. I woke up a couple of times to hear things moving about outside and colobus monkeys barking in the trees above. By 5.30 a.m. I was up and about, as were a vast range of different birds, judging by the Omo dawn chorus. I packed a rucksack with essentials: medical kit, some cereal bars, camera, Ventolin inhalers, notebook, GPS and map, as well as several boxes of crayons and a selection of small toy cars. I filled my Camelback reservoir to the brim, and I took an extra two-litre bottle of water as well. Then Enku and I set off in the Land Cruiser to catch a boat across the Omo.

After a bumpy ride along a dusty dirt track, we pulled up next to the riverbank, opposite the village of Kangaten. We waved at the boatman on the other side, and he brought his boat across. It was small, with a modest outboard motor, but its skipper knew how to beat the swift current by taking it in a wide arc, heading upriver first then falling back alongside us as he approached the near bank. I scrambled into the boat and off we went again, over to Kangaten. I had seen crocodiles in the Omo as I’d flown in, and when I asked the boatman if there were any around he smiled and nodded. I didn’t see any, although the odd log drifting down the river made me look twice.

On the other side, it seemed as if most of the village had turned up to greet us.

Lots

of children swarmed around. I took photographs and they clustered around me, squealing in delight as I showed them the photos on the camera. They pointed and laughed as they recognised each other in the tiny screen. Before Enku and I embarked into the four-wheel-drive that was waiting for us on this side of the river, I handed out coloured wax crayons and toy cars. Some of the kids looked healthy, but others displayed the swollen bellies and stick-thin legs of malnutrition. I also spotted patches of skin infection and ringworm on their bare bodies and faces. They were much less healthy than the children in the Bushmen village. I felt as though I should have brought medical supplies and food rather than crayons and toys. I also felt that familiar pang of guilt that I was an academic, not a practising medical doctor any more. At such times I have to remind myself that teaching and research are worthwhile. And I know that Ethiopia’s problems can’t be solved by aid workers alone. I handed out my cereal bars and got into the car.

Enku introduced me to Soya, who would act as my translator when we reached the village of Kibish. I knew that people from that village had been involved with the dig and discoveries at Omo, and that, more recently, they had helped Ian McDougall and his team when they visited the site. Although I had the map and the coordinates published by McDougall, I was aware that I might end up going hugely out of my way in the bush if I tried to find the site on my own, without help from locals who knew the landscape and the paths through it. And I really didn’t want to get lost in the bush. Another issue was security. The tribes around the Omo River – the Mursi, Bumi, Hamer, Karo, Surma and Turkana – seemed constantly to be fighting each other, and there were a lot of men wandering about with guns.

After a further drive along dusty tracks through the bush, having stopped to talk to a group of men with guns who were apparently local police, we reached Kibish. The huts of the village were surrounded by a dense thorny fence, with a slit-like entrance that was hard to discern but presumably excellent for keeping out hyenas or other tribesmen. Soya led the way and took me to the chief, Ejem. Most people in the village seemed to be dressed fairly traditionally. The women wore knee-length apron-like skirts, and masses of bead necklaces on their bare chests. Many had red ochre painted on their chests, necks, faces and braided hair. Smaller children ran around naked. Older ones had painted faces and cloths tied loosely round their waists. One boy was wearing a faded, red David Beckham T-shirt. Some men were dressed traditionally, with small skirts and collars of beads, but the chief, Ejem, was wearing flamboyant basketball shorts, a plastic leopard-print cowboy hat and a necklace of red and yellow beads. His status was made obvious by the wearing of these exotic items.

With Soya translating, I introduced myself to the chief and asked him if anyone knew the place where the fossils had been found. Ejem called over one man and pointed to him. Soya translated. ‘Here is one man, the other is coming.’ This first man, Kapuwa, was wearing a T-shirt and a brown cloth hat with a turned-up red brim, and carrying a gun. He talked to Soya and I grew excited as he pointed off into the distance and made digging motions with his hands.

‘Soya, what did he say?’

‘He said, “There was someone with a camera and someone was digging. He found something like a bone, which had stayed there for a long time. I know exactly the place and I can show you now.”’

The second guide, Logela, had now come over as well. He was wearing a yellow cloth hat, set at a jaunty angle on his head.

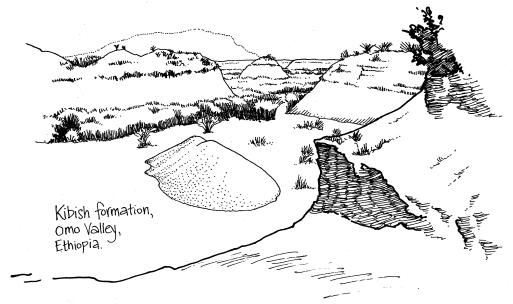

So Kapuwa, Logela, Soya and I headed off into the bush. We drove for about 4km away from Kibish, through flat, scrubby bush, until we reached an area with dune-like hills and deep channels: the Kibish formation. It was impossible to take the car any further. I waymarked the car on the GPS before striking out into the wilderness. Even though I had started as early as possible that morning, I was still having to walk in the heat of the midday sun. And Logela and Kapuwa set a fairly intense pace. Logela was carrying a gun, and I asked Soya how often violence broke out between tribes.

Apparently it was a fairly common occurrence, but, as we weren’t after anyone’s cattle, we ought to be safe. It was still just as well to have a gun, though.

‘Did you see the scarification on the chief’s chest?’ Soya asked me. I had. ‘It means he is a hero: he has killed a man.’

As we walked, we did meet a couple of other lone men with guns, and I was very grateful for the security of travelling with Soya and the guides from Kibish. And they did seem to know where they were heading. We walked down through the barren valleys of the Kibish formation, which was like a lunar landscape. Then we were on the flood plain again and close to the Omo. As we tracked up the west bank of the river, I started to feel heady and overheated, and so we stopped for a while. We had been going for about an hour, and the sun was now at its highest point, directly overhead and beating down. I drank more water and wrapped a silk scarf around my head, then we carried on. We passed a ridge, perpendicular to the river, and the guides pointed to another, similar ridge. Soya told me that they thought we were almost at the spot. I was very glad; I was starting to feel as if I might have to turn back without reaching the site, but now I knew we were close I could summon the determination to carry on.

We marched on, along dusty paths through the bush that looked as though they were used more often by animals than people. Umbrella thorns (

Acacia tortillis

) raised their branches above the other shrubs, and every now and then, among the scrubby bushes, there would be a beautiful little Elemu tree, with five-petalled pink flowers. It seemed strange in this dry and dusty landscape to see something so exuberantly colourful. These shrubs were between one and two metres high, with bottle-bottomed trunks and very bendy branches, I discovered, by doing just that – bending them. And then, as we walked up to the second ridge, Logela and Kapuwa came to a halt and gestured round at the landscape. ‘This is the place,’ said Soya.

We were standing at the foot of the ridge, with smooth, light-brown slopes formed of silty sediments, shaped by the biannual flooding. There were also a couple of darker layers, one close to ground level, the other higher up the slopes. On closer inspection, these layers were harder rock, dark brown and almost black in places. The bottom of the slope was covered with fragments of this tuff .