The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis (44 page)

Read The Indomitable Spirit of Edmonia Lewis Online

Authors: Harry Henderson

Tags: #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY, #BIOGRAPHY

The necktie was, of course, a staple of fashion more prim than an open collar.

In 1876, a Centennial correspondent confirmed, “She is about medium height, with a pretty and interesting face. Her soft brown eyes are an index of a pleasant, and her smiling face of a merry, disposition. Her manners are unaffected and charming, while her conversation is bright, affable and witty. She is quite an accomplished linguist, and is remarkably shrewd and intelligent.”

[707]

A few years later, a Boston critic capped a summary of her life and work by describing her as, “a lady of much grace and pleasing address.”

[708]

The most troubling truth is that Edmonia suffered most at the hands of fellow artists in Rome, male and female. Horace Greeley’s niece recalled them slicing and dicing with relish:

While we were in Rome four or five years ago … I heard much talk about [Edmonia] from her brother and sister artists. I intended at one time to visit her studio and see her work, but several sculptors advised me not to do so; she was, they declared, “queer,” “unsociable,” often positively rude to her visitors, and had been heard to fervently wish that the Americans would not come to her studio, as they evidently looked upon her only as a curiosity. When, therefore, I did see her for the first time (last summer), I was much surprised to find her by no means the morose being that had been described to me, but possessed of very soft and quite winning manners.

She was amused when I told her what I had heard of her.

[709]

“Amused,” but not surprised, she would likely shudder to read twentieth century claims about her as gruff and mean. She pointed out to Greeley’s niece, “How could I expect to sell my work if I did not receive visitors civilly?”

In Edmonia’s lifetime, mixed blood became a national fetish. Emotional hype of “scientific” certainty directed fears that blood shaped one’s nature and ability. It was blood, not looks, that obsessed the makers of Jim Crow laws. Who was “pure?” Who was not? They sought to exclude every drop of the African essence from white society, where light eyes, hair, and skin might mislead and excuse a pass.

Three words – “mulatto,” “quadroon,” and “octoroon,” each defining fractions of African blood – made their way into the official 1890 U. S. census form. The idea was that the survey would provide new proof of white advantage in statistical form.

[710]

There was no plan. The data defied analysis in spite of the new Hollerith system with punch cards and electric tabulation machines.

The honest details of forebears, however, threatened a forest of family trees. The 1890 data barely endured fires in 1896 and 1921. The records finally vanished, destroyed without a blink in 1933 as “papers no longer necessary for current business.”

[711]

In a more bizarre example of blood “science,” the

Phrenological Journal

perverted the 1870

Art-Journal

report of Cholmeley’s attempt to symbolize Edmonia’s dual heritage. Its brazen quack claimed to have met with Edmonia, the lie lending trust to his report that her hair actually differed from one side of her head to the other.

The

Christian Recorder

reprinted the sham nearly verbatim, coyly remarking, “The reading, is of the usual excellence.”

[712]

A few other editors in America, impish, rude, and looking for sensation, noted only the unusual dualism.

[713]

The Decline of Rome’s Arts Colony - 1879

By 1879, the “strange sisterhood” had scattered like pearls on a flagstone patio. Its leader, ailing and depressed, departed Rome in 1870 with Emma Stebbins and Sallie Mercer in tow. She finally died in February 1876, having spent her last days in Boston where her School Street rooms overlooked the bronze

Franklin

that had set off Edmonia’s career. Emma, who published Charlotte’s letters two years later, never returned to Rome or sculpted again.

Florence Freeman, compared by some to Hilda of

The Marble Faun,

also died in 1876. A good pal of Hosmer’s, Florence had taken a studio next door to Edmonia’s.

Hosmer, though often absent, kept her Via Margutta studio until 1879.

[714]

She then based herself in England where Lady Ashburton had bought so many of her works neither could keep track of who owned what.

Margaret Foley died in 1877 as she vacationed in the Austrian Tyrol.

Grace Greenwood, who came to Rome with Hosmer and Cushman, had quickly returned to America, married her publisher, and bore him a daughter. By 1879, she was single again, still writing professionally in the United States.

After her memorable year in Rome, Vinnie Ream left, never to return. In 1878, she married

Richard L. Hoxie, a lieutenant in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and blossomed in the social whirl of Washington DC.

Edmonia’s best friend, Isabel Cholmeley,

moved to Venice before 1877 where she continued to entertain and sculpt as

Contessa Isabel Curtis-Cholmeley

in Bermani. The Italian title came from her new husband, an official of the Venice government.

[715]

Anne Whitney returned to Boston in 1871 with Abby Manning, lightheartedly fibbing about their ages to the clerk of the new Cunard liner and posting their occupations as “voyager.”

[716]

Anne had never met Maria Child, but by 1877 she had approached her with an offer to do her portrait.

Child declined, but she made Anne “her last adopted daughter.”

[717]

They became close, visiting overnight, and writing – Maria addressing Anne as “Saucebox” and signing as “Bird o’ Freedom.”

[718]

In 1884, Anne carved a marble bust of Samuel E. Sewall, the man at the center of Edmonia’s 1868 disaster. Inevitably, she and Maria must have minced Edmonia’s fame as they took time “to settle the affairs of the universe”

[719]

off the record.

More than ever, reflections on her orphan past set Edmonia’s agenda. She arranged for

The Death of Cleopatra

to appear at a bazaar for Chicago’s Home for the Friendless, a gigantic orphanage founded around 1850.

[720]

She also promised to help the Sisters of Charity, an order that looked after homeless children and invalids in Cincinnati.

[721]

To that end, she returned to America in mid-1879, wealthy enough to take a cabin on the most modern ship available, her work presumably in its hold. She was vain enough to claim an age of twenty-nine (at the age of thirty-five) and to list her occupation as “Lady.”

[722]

In the aftershocks of the Civil War, the tsunami of Reconstruction swamped Southern society and the media. Now its energy was spent. Newspapers and politics twisted in the rip tides of political retrenchment. News of colored talent was no longer welcome.

It is likely the

New York Times

editors saw the change coming when they spotlighted her reception a few months earlier. They covered her with an

untitled

interview, the last first-hand report in that august journal. In it, they unleashed as much additional detail as they could muster.

[723]

Other news services noted her life-size marble only briefly, some accepting her ever-bolder claims to be only twenty-four years old. Seeing a

tour de force

in which a face of stone seemingly appears behind a gauzy membrane, someone decided to call it the

Veiled Bride of Spring

(Figure 48-49).

[724]

She stopped to show it in Syracuse, New York – an interesting turn. On her way to the Good Samaritan Hospital in Cincinnati, she paused in the town that once forced her to find shelter with a good samaritan.

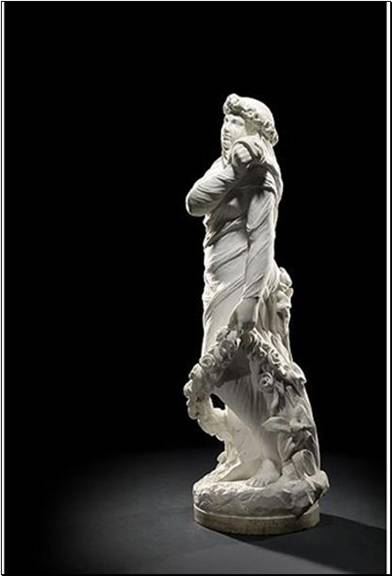

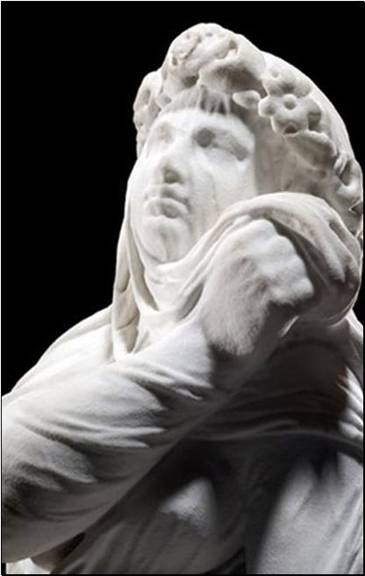

Figure 48. The “Veiled”

Bride of Spring,

1879

This exceptional gift to a Catholic orphanage was discovered in a Kentucky library and returned to Cincinnati for auction in the fall of 2007. Photo courtesy Cowan’s Auctions.

Figure 49. The “Veiled”

Bride of Spring,

detail

This detail of the veiled face focuses on a gray streak that appears to be from tears. It is natural veining in the marble that the artist incorporated in her design. Weather dulled the original highly polished finish.

[725]

Photo courtesy Cowan’s Auctions.

The next year, she produced a smaller and similarly “veiled”

Spring.

We found no hint she intended it to benefit a religious group – it is more sensuous, with wraps that cling to hips and thighs. A scion of a wealthy Boston family showed

Spring

in Boston the following year.

[726]

Unlabeled portraits test the archivist of history as well as the historian of art. For some of Edmonia’s portraits, there is little hope of recovering a name. The man in Edmonia’s sensitive 1879 bust (Figure 50) may be an exception. His garb indicates a church leader.

Comparisons with hundreds of engravings and photos yield few possibilities. One was Bishop Christopher Rush, recently deceased at the time. He helped found the New York-based AME Zion Church in 1821

[727]

Until blindness forced his retirement in the 1850s, he served as its second bishop. He wielded a huge influence in his time, and he was highly revered.

[728]

When he died in 1873, he had lived nearly a full century.

A memorial portrait could have been planned in 1877, the centenary of his birth, and ordered during Edmonia’s 1878 tour. That year she visited New York and Indianapolis, the former city being where the Church was founded, the latter host to the Jones Tabernacle AME Zion Church and the largest congregation in the city.

[729]

While not certain, he seems recognizable by his robust hairline, his strong cheekbones, his eyebrows and nose, the symmetry of features, and the stylized garb favored by his cofounders.

[730]

Edmonia did not depict the elderly blind man she might have met. Idealized in her hands, the image reflects vigorous youth, a visionary squint, and a Lincolnesque beard not seen in engravings. Her use of painted plaster suggests that she aimed for a reasonable price, as she did with her portrait of Bishop Arnett (Figure 46).

Other possibilities exist, such as Willis Nazery, fifth bishop of the AME Church.

[731]

He was active in an Underground Railroad destination in Canada at the western tip of Lake Erie. In a portrait engraving, he also bears a resemblance in features and attire. The logistics of a commission seem less likely. Christopher Busta-Peck suggested it portrays the African-American abolitionist Robert Purvis.

[732]

Figure 50. African-American clergyman, 1879

This 24-inch high plaster bust was patinated (covered with metallic paint) to resemble bronze. Photo courtesy: American Museum of Natural History Library.

[733]