The Information (8 page)

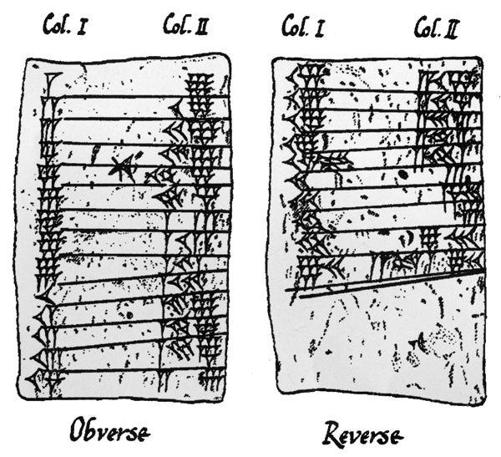

A MATHEMATICAL TABLE ON A CUNEIFORM TABLET ANALYZED BY ASGER AABOE

These symbols were hardly words—or they were words of a peculiar, slender, rigid sort. They seemed to arrange themselves into visible patterns in the clay, repetitious, almost artistic, not like any prose or poetry archeologists had encountered. They were like maps of a mysterious city. This was the key to deciphering them, finally: the ordered chaos that seems to guarantee the presence of meaning. It seemed like a task for mathematicians, anyway, and finally it was. They recognized geometric progressions, tables of powers, and even instructions for computing square roots and cube roots. Familiar as they were with the rise of mathematics a millennium later in ancient Greece, these scholars were astounded at the breadth and depth of mathematical knowledge that existed before in Mesopotamia. “It was assumed that the Babylonians had had some sort of number mysticism or numerology,” wrote Asger Aaboe in 1963, “but we now know how far short of the truth this assumption was.”

♦

The Babylonians computed linear equations, quadratic equations, and Pythagorean numbers long before Pythagoras. In

contrast to the Greek mathematics that followed, Babylonian mathematics did not emphasize geometry, except for practical problems; the Babylonians calculated areas and perimeters but did not prove theorems. Yet they could (in effect) reduce elaborate second-degree polynomials. Their mathematics seemed to value computational power above all.

That could not be appreciated until computational power began to mean something. By the time modern mathematicians turned their attention to Babylon, many important tablets had already been destroyed or scattered. Fragments retrieved from Uruk before 1914, for example, were dispersed to Berlin, Paris, and Chicago and only fifty years later were discovered to hold the beginning methods of astronomy. To demonstrate this, Otto Neugebauer, the leading twentieth-century historian of ancient mathematics, had to reassemble tablets whose fragments had made their way to opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean. In 1949, when the number of cuneiform tablets housed in museums reached (at his rough guess) a half million, Neugebauer lamented, “Our task can therefore properly be compared with restoring the history of mathematics from a few torn pages which have accidentally survived the destruction of a great library.”

♦

In 1972, Donald Knuth, an early computer scientist at Stanford, looked at the remains of an Old Babylonian tablet the size of a paperback book, half lying in the British Museum in London, one-fourth in the Staatliche Museen in Berlin, and the rest missing, and saw what he could only describe, anachronistically, as an algorithm:

A cistern.

The height is 3,20, and a volume of 27,46,40 has been excavated.

The length exceeds the width by 50.

You should take the reciprocal of the height, 3,20, obtaining 18.

Multiply this by the volume, 27,46,40, obtaining 8,20.

Take half of 50 and square it, obtaining 10,25.

Add 8,20, and you get 8,30,25.

The square root is 2,55.

Make two copies of this, adding to the one and subtracting from the other.

You find that 3,20 is the length and 2,30 is the width.

This is the procedure.

♦

“This is the procedure” was a standard closing, like a benediction, and for Knuth redolent with meaning. In the Louvre he found a “procedure” that reminded him of a stack program on a Burroughs B5500. “We can commend the Babylonians for developing a nice way to explain an algorithm by example as the algorithm itself was being defined,” said Knuth. By then he himself was engrossed in the project of defining and explaining the algorithm; he was amazed by what he found on the ancient tablets. The scribes wrote instructions for placing numbers in certain locations—for making “copies” of a number, and for keeping a number “in your head.” This idea, of abstract quantities occupying abstract places, would not come back to life till much later.

Where is a symbol? What is a symbol? Even to ask such questions required a self-consciousness that did not come naturally. Once asked, the questions continued to loom.

Look at these signs

, philosophers implored.

What are they

?

“Fundamentally letters are shapes indicating voices,”

♦

explained John of Salisbury in medieval England. “Hence they represent things which they bring to mind through the windows of the eyes.” John served as secretary and scribe to the Archbishop of Canterbury in the twelfth century. He served the cause of Aristotle as an advocate and salesman. His Metalogicon not only set forth the principles of Aristotelian logic but urged his contemporaries to convert, as though to a new religion. (He did not mince words: “Let him who is not come to logic be plagued with continuous and everlasting filth.”) Putting pen to parchment in this time of barest literacy, he tried to examine the act of writing and the effect of words: “Frequently they speak voicelessly the utterances of the absent.”

The idea of writing was still entangled with the idea of speaking. The mixing of the visual and the auditory continued to create puzzles, and so also did the mixing of past and future: utterances of the absent. Writing leapt across these levels.

Every user of this technology was a novice. Those composing formal legal documents, such as charters and deeds, often felt the need to express their sensation of speaking to an invisible audience: “Oh! all ye who shall have heard this and have seen!”

♦

(They found it awkward to keep tenses straight, like voicemail novices leaving their first messages circa 1980.) Many charters ended with the word “Goodbye.” Before writing could feel natural in itself—could become second nature—these echoes of voices had to fade away. Writing in and of itself had to reshape human consciousness.

Among the many abilities gained by the written culture, not the least was the power of looking inward upon itself. Writers loved to discuss writing, far more than bards ever bothered to discuss speech. They could

see

the medium and its messages, hold them up to the mind’s eye for study and analysis. And they could criticize it—for from the very start, the new abilities were accompanied by a nagging sense of loss. It was a form of nostalgia. Plato felt it:

I cannot help feeling, Phaedrus, [says Socrates] that writing is unfortunately like painting; for the creations of the painter have the attitude of life, and yet if you ask them a question they preserve a solemn silence.… You would imagine that they had intelligence, but if you want to know anything and put a question to one of them, the speaker always gives one unvarying answer.

♦

Unfortunately the written word stands still. It is stable and immobile. Plato’s qualms were mostly set aside in the succeeding millennia, as the culture of literacy developed its many gifts: history and the law; the sciences and philosophy; the reflective explication of art and literature itself. None of that could have emerged from pure orality. Great poetry could and did, but it was expensive and rare. To make the epics of Homer, to

let them be heard, to sustain them across the years and the miles required a considerable share of the available cultural energy.

Then the vanished world of primary orality was not much missed. Not until the twentieth century, amid a burgeoning of new media for communication, did the qualms and the nostalgia resurface. Marshall McLuhan, who became the most famous spokesman for the bygone oral culture, did so in the service of an argument for modernity. He hailed the new “electric age” not for its newness but for its return to the roots of human creativity. He saw it as a revival of the old orality. “We are in our century ‘winding the tape backward,’ ”

♦

he declared, finding his metaphorical tape in one of the newest information technologies. He constructed a series of polemical contrasts: the printed word vs. the spoken word; cold/hot; static/fluid; neutral/magical; impoverished/rich; regimented/creative; mechanical/organic; separatist/integrative. “The alphabet is a technology of visual fragmentation and specialism,” he wrote. It leads to “a desert of classified data.” One way of framing McLuhan’s critique of print would be to say that print offers only a narrow channel of communication. The channel is linear and even fragmented. By contrast, speech—in the primal case, face-to-face human intercourse, alive with gesture and touch—engages all the senses, not just hearing. If the ideal of communication is a meeting of souls, then writing is a sad shadow of the ideal.

The same criticism was made of other constrained channels, created by later technologies—the telegraph, the telephone, radio, and e-mail. Jonathan Miller rephrases McLuhan’s argument in quasi-technical terms of information: “The larger the number of senses involved, the better the chance of transmitting a reliable copy of the sender’s mental state.”

♦

♦

In the stream of words past the ear or eye, we sense not just the items one by one but their rhythms and tones, which is to say their music. We, the

listener or the reader, do not hear, or read, one word at a time; we get messages in groupings small and large. Human memory being what it is, larger patterns can be grasped in writing than in sound. The eye can glance back. McLuhan considered this damaging, or at least diminishing. “Acoustic space is organic and integral,” he said, “perceived through the simultaneous interplay of all the senses; whereas ‘rational’ or pictorial space is uniform, sequential and continuous and creates a closed world with none of the rich resonance of the tribal echoland.”

♦

For McLuhan, the tribal echoland is Eden.

By their dependence on the spoken word for information, people were drawn together into a tribal mesh … the spoken word is more emotionally laden than the written.… Audile-tactile tribal man partook of the collective unconscious, lived in a magical integral world patterned by myth and ritual, its values divine.

♦

Up to a point, maybe. Yet three centuries earlier, Thomas Hobbes, looking from a vantage where literacy was new, had taken a less rosy view. He could see the preliterate culture more clearly: “Men lived upon gross experience,” he wrote. “There was no method; that is to say, no sowing nor planting of knowledge by itself, apart from the weeds and common plants of error and conjecture.”

♦

A sorry place, neither magical nor divine.

Was McLuhan right, or was Hobbes? If we are ambivalent, the ambivalence began with Plato. He witnessed writing’s rising dominion; he asserted its force and feared its lifelessness. The writer-philosopher embodied a paradox. The same paradox was destined to reappear in different guises, each technology of information bringing its own powers and its own fears. It turns out that the “forgetfulness” Plato feared does not arise. It does not arise because Plato himself, with his mentor

Socrates and his disciple Aristotle, designed a vocabulary of ideas, organized them into categories, set down rules of logic, and so fulfilled the promise of the technology of writing. All this made knowledge more durable stuff than before.

And the atom of knowledge was the word. Or was it? For some time to come, the word continued to elude its pursuers, whether it was a fleeting burst of sound or a fixed cluster of marks. “Most literate persons, when you say, ‘Think of a word,’ at least in some vague fashion think of something before their eyes,” Ong says, “where a real word can never be at all.”

♦

Where do we look for the words, then? In the dictionary, of course. Ong also said: “It is demoralizing to remind oneself that there is no dictionary in the mind, that lexicographical apparatus is a very late accretion to language.”

♦

♦

It is customary to transcribe a two-place sexagesimal cuneiform number with a comma—such as “7,30.” But the scribes did not use such punctuation, and in fact their notation left the place values undefined; that is, their numbers were what we would call “floating point.” A two-place number like 7,30 could be 450 (seven 60s + thirty 1s) or 7½ (seven 1s + thirty 1/60s).

♦

Not that Miller agrees. On the contrary: “It is hard to overestimate the subtle reflexive effects of literacy upon the creative imagination, providing as it does a cumulative deposit of ideas, images, and idioms upon whose rich and appreciating funds every artist enjoys an unlimited right of withdrawal.”

♦

The interviewer asked plaintively, “But aren’t there corresponding gains in insight, understanding and cultural diversity to compensate detribalized man?” McLuhan responded, “Your question reflects all the institutionalized biases of literate man.”