The Insistent Garden

The Insistent Garden

The

INSISTENT

GARDEN

a

novel

ROSIE CHARD

COPYRIGHT © ROSIE CHARD 2013

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior consent of the publisher is an infringement of the copyright law. In the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying of the material, a licence must be obtained from Access Copyright before proceeding.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Chard, Rosie, 1959â

The insistent garden / Rosie Chard.

Issued also in an electronic format. isbn 978-1-927063-38-5

I. Title.

PS

8605.

H

3667i67 2013Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â

C

813'.6Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â

C

2013-901541-8

Editor for the Board: Douglas Barbour

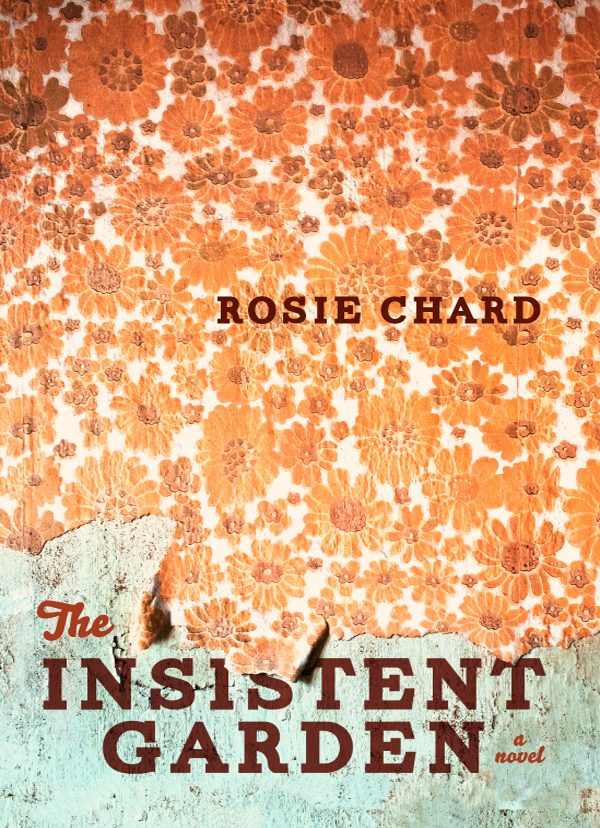

Cover and interior design: Natalie Olsen, Kisscut Design

Cover photo: wallpaper © suze /

photocase.com

Author photo: Nat Chard

NeWest Press acknowledges the financial support of the Alberta Multimedia Development Fund and the Edmonton Arts Council for our publishing program. We further acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (

CBF

) for our publishing activities. We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts which last year invested $24.3 million in writing and publishing throughout Canada.

#201, 8540â109 Street

Edmonton, Alberta

T

6

G

1

E

6

780.432.9427

www.newestpress.com

No bison were harmed in the making of this book.

printed and bound in Canada 1Â 2Â 3Â 4Â 5Â 14Â 13

For Phoebe

And so faintly you came tapping, tapping at my chamber door,

That I scarce was sure I heard you

EDGAR ALLAN POE,

“THE RAVEN”

Contents

I was sweeping the porch with the wide broom when I found the fly. A live fly, it was sealed inside the bottle of milk waiting on the doorstep. I knew it was still alive even before I picked up the cold glass and peered inside. Its legs waved frantically and its body drifted in a wave of milk that slapped against the sides with every movement of my hand.

I glanced up the street, and then looked towards my neighbour's hedge; just leaves, just twigs.

“What's wrong with the milk?” my father said, as I entered the kitchen.

“There's a fly inside the bottle,” I replied.

“Who put it there?” my father said, frowning.

“No-one.” I placed the bottle on the draining board. “It. . . it just happened.”

“

He

did it!” My father shoved back his chair, his neck tall with anger. I drew in a breath. Of course he had done it; there was no doubt in my father's mind.

He

had sneaked into our garden while it was still dark and stolen the milk from the doorstep. He had removed the lid with a knife, captured the fly and dropped it into the bottle. The bottle was now sealed. The milk was now tainted; I could almost see the limp feeding tube dipping into the liquid like a straw, not sucking up, but leaching downwards.

“I can throw it away,” I said.

“No, I'll do it.” My father stepped towards me and closed his fingers round the glass neck. A whiff of mothballs wafted out from beneath his armpit as he lifted the bottle up, opened the back door and disappeared into the garden, leaving a rectangle of early morning sunshine lying on my feet. A shadow fell onto my toes and I looked up just in time to see my father's raised arm silhouetted against the sky.

I rushed out of the back door. “No, please!” But it was too late. The trapped fly was airborne again; it soared over the garden wall like a white bird. As the sound of breaking glass raced back into our garden I clamped my hands over my ears and looked up at the wall that divided us from our neighbour.

He

had the fly now.

He deserved it.

I knew the back of my father's ankles intimately â especially that segment of skin between the top of his socks and the bottom of his trousers. A small forest of leg hair was exposed every time he stretched up the ladder to press mortar into a high part of the garden wall and I often felt the desire to tuck the stray tufts back into his sock. His shoes were scuffed too, down the back seam, and I sometimes wondered what mythical creature rubbed that precise spot.

“Pass me up that cloth,” he said, glancing down at the bucket beside my feet.

“Yes.” I replied, too quickly.

The slime impregnating the cloth conjured up memories of frogspawn, but I managed to wring it out without changing expression and held it up to my father's waiting hand. This was what I did. Bend down; wring out; pass up.

For as long as I could remember my father and I had been working on the garden wall. Not an ordinary wall. Not a low boundary just high enough for neighbours to rest their elbows on and discuss the weather. Not even a lovingly crafted brick divider, marking the back of a flower bed. Our wall was a barricade, designed to keep out the enemy. It began at the corner of our house and ran down one side of the garden before coming to a halt at the back fence, over a hundred feet away. It used to be like other people's walls, low, straight, often warm â the perfect place against which to lean â but my father had built it up over the years, adding extra layers with new bricks and off-cuts and materials he'd found in the street and now it reached eight feet if the chalk mark scratched halfway up could be trusted. I couldn't remember life without the wall. I'd tried. I'd often walked its length from house to back fence, running my hand along the bricks as I attempted to recall a time when our garden looked the same as every other in the street.