The Internet of Us (12 page)

Read The Internet of Us Online

Authors: Michael P. Lynch

Objectivity and Our Constructed World

Life in the Internet of Us can make it hard to know what is true. That's partly because the digital world is a constructed world, but

one constructed by a gazillion hands, all using different plans. And it is partly because it seems increasingly difficult to step outside of our constructed reality.

These facts have led some to claim that objectivity is dead. Internet theorist David Weinberger, for example, has suggested that objectivity has fallen so far “out of favor in our culture” that the Professional Journalists' Code of Ethics dropped it as an official value (in 1996, no less). Weinberger himself argues that our digital form of life undermines the importance of objectivity, in part because humans always “understand their world from a particular viewpoint.” That's a problem, apparently, because objectivity rests on a metaphysical assumption: “Objectivity makes the promise to the reader that the [news] report shows the world as it is by getting rid of (or at least minimizing) the individual, subjective elements, providing, [in the philosopher Thomas Nagel's words], âthe view from nowhere.' ”

15

For Weinberger, objectivity is an illusion because there is no such thing as a view from nowhere.

Maybe not. But that doesn't rule out objectivityâsince being objective doesn't require a view from nowhere. Truths are objective when what makes them true isn't just up to us, when they aren't constructed. But a

person

is objective, or has an objective attitude, to the extent to which he or she is sensitive to reasons. Being sensitive to reasons involves being aware of your own limitations, being alert to the fact that some of what you believe may not be coming from reasons but from your own prejudices, your own viewpoint alone. Objectivity requires open-mindedness. It doesn't require being sensitive to reasons that (impossibly) can be assessed from no point of view. It means being sensitive to

reasons that can be assessed from multiple and diverse points of view. Being objective in this sense may not always, as Locke would have acknowledged, necessarily bring us closer to the real truth of the matter, to what Kant called “things in themselves.” But that is just to repeat what we already know: being objective, or sensitive to reasons, is no guarantee of certainty.

In Weinberger's view, objectivity “arose as a public value largely as a way of addressing a limitation of paper as a medium for knowledge.”

16

The need to be objective, he argues, stems from the fact that paperâhe means the printed word, roughlyâis a static medium; it forces you to “include everything that the reader needs to understand a topic.” In his view, the Internet has replaced the value of objectivity with transparencyâin two ways. First, the Internet makes it easy to look up a writer's viewpoint, because you can most likely find a host of information about that writer. And second, it makes a writer's sources more open: a hyperlink can take you right to them, allowing you to check them out for yourself.

I agree that transparency in both of these senses is a value. And our digital form of life has, indeed, increased transparency in some waysâbut not in all. It has increased transparency for those who already desire and value it. But as the use of sock puppets and bots demonstrates, the ability of the Internet to allow deceptive communication leads in precisely the opposite direction. Moreover, we value being able to check on sources and background precisely because we value objective reasonsâreasons that are not reasons only for an individual but are valid for diverse viewpoints. We want to know whether the source of our information is biased because we want to sort out that bias from those facts that we can

appreciate independently of bias. Transparency is not a replacement for valuing objectivity; it is valuable because we value objectivity.

Just as we can't let the maze of our digital life convince us to give up on objectivity and reasons, it shouldn't lead us to think that all truth is constructed, that truth is whatever passes for truth in our community, online or off. What passes for truth in a community can be shaped all too easily. That's what the noble lie is all about. What passes for truth is vulnerable to the manipulations of power. So, if truth is only what passes for truth, then those who disagree with the consensus areâby definitionânot capable of speaking the truth. It's no surprise, then, that the idea that truth is constructed by opinion has been the favorite of the powerful. In the immortal words of a senior Bush advisor, “We are an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality.”

17

That, fundamentally, is why we should hold onto the idea that at least

some

truth is not constructed by usâeven if the digital world in which we live is. Give up that thought, and we undermine our ability to engage in social criticism: to think beyond the consensus, to see what is really there.

Who Wants to Know: Privacy and Autonomy

In 1890, Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis published an article in the

Harvard Law Review

arguing for what they dubbed “the right to privacy.” It made a splash, and is now one of the most widely cited legal articles in U.S. history. What is less known is what precipitated the article. The Kodak camera had just been invented, and it (and cameras like it) was being used to photograph celebrities in unflattering situations. Because of this newfangled invention, Warren and Brandeis worried that technologyâand our unfettered use of itâwas negatively affecting the individual's right to control access to private information. Technology seemed to be outstripping our sense of how to use it ethically.

They had no idea.

In the first part of this book, we've seen how some ancient philosophical challenges have become new again. We've grappled with whether “reasonableness” is reasonable and whether truth is a fantasy. But these old problems are only half the story. To really appreciate how we can know more but understand less, we need to recognize what is distinctive about how we know now. And a good place to start is with this simple fact: the things we carry allow us to know more than ever about the world, faster than ever. But they also allow the world to know more about usâand in ways never dreamed of by Warren and Brandeis. Knowledge has become transparent. We look out the window of the Internet even as the Internet looks back in.

Most of the data being collected in the big data revolution is about us. “Cookies”âthose insidious (and insidiously named) little Internet geniesâhave allowed websites to track our clicking for decades. Now much more sophisticated forms of data analysis allow the lords of big data, like Google and Amazon, to form detailed profiles of our preferences. That's what makes the now ubiquitous targeted ad possible. Searching for new shoes? Google knowsâand will helpfully provide you with an ad showing a selection of the kind of shoes you are looking for the next time you visit nytimes.com. And you don't have to click to be tracked. The Internet of Things means that your smartphone is constantly spewing data that can be mined to find out how long you are in a store, which parts of the store you visit and for how long, and how much, on average, you spend and on what. Your new car's “black box” data recorder keeps track of how fast you are traveling, where you have traveled and whether you are wearing your seatbelt. That's on top

of much older technologies that continue to see widespread useâsuch as the CCTV monitors that record events at millions of locations across the globe.

And, of course, data mining isn't done just for business purposes. Arguably, the United States' largest big data enterprise is run by the NSA, which was intercepting and storing an estimated 1.7 billion emails, phone calls and other types of communications

every single day

(and that was way back in 2010).

1

As I write this, the same organization is purported to be finishing the building of several huge research centers to store and analyze this data around the country, including staggeringly large million-square-foot facilities in remote areas of the United States.

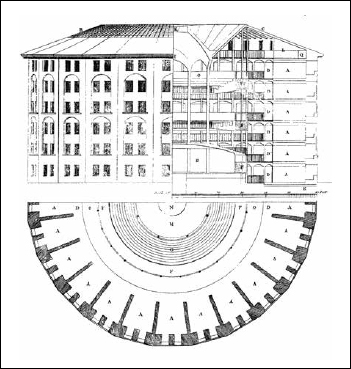

We all understand that there is more known about what each of us thinks, feels and values than ever before. It can be hard to shake the feeling that we are living in an updated version of Jeremy Bentham's famous panopticonâan eighteenth-century building design that the philosopher suggested for a prison. The basic idea was a prison as a fishbowl. Observation, Bentham suggested, affects behaviorâand prisoners would control their behavior more if they knew their privacy was completely gone, if they could be seen by and see everyone at all times.

In some ways, our digital lives are fishbowls; but fishbowls we've gotten into willingly. One of the more fascinating facts about the amount of tracking going on in the United States is that hardly anyone seems to care. That might be due not to underreporting or lack of Internet savvy by the public (although both are true) but to the simple fact that the vast majority of people are simply used to it. Moreover, there are lots of positives. Targeted ads can be helpful, and smartphones have become effectively indispensable for many of us. And few would deny that increased security from terrorism is a good thing.

Fig. 2. Elevation, section and plan of Jeremy Bentham's Panopticon penitentiary, drawn by Willey Reveley, 1791.

Partly for these reasons, writers like Jeremy Rifkin have been saying that information privacy is a worn-out idea. In this view, the Internet of Things exposes the value of privacy for what it is: an idiosyncrasy of the industrial age.

2

So no wonder, the thought goes, we are willing to trade it awayânot only for security, but for the increased freedom that comes with convenience.

This argument rings true because in some ways it

is

true: we do, as a matter of fact, have more freedom because of the Internet and its box of wonders. But, as with many arguments that support the status quo, one catches a whiff of desperate rationalization

as well. In point of fact, there is a clear sense in which the increased transparency of our lives is not enhancing freedom but doing exactly the oppositeâin ways that are often invisible.

Part II

Part II