The Internet of Us (5 page)

Read The Internet of Us Online

Authors: Michael P. Lynch

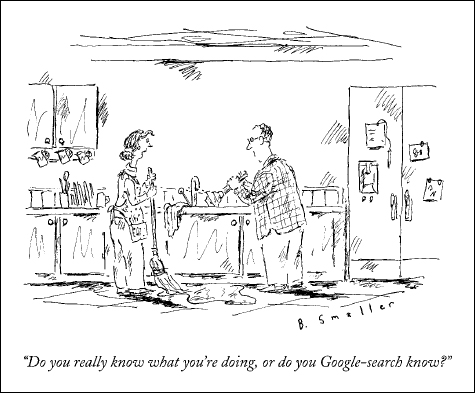

Fig. 1. Courtesy of Barbara Smaller/The New Yorker Collection/The Cartoon Bank

So, “Google-knowing” helps describe how we acquire information and knowledge via the testimony machine of the Internet. It is easy, fast

and yet dependent on others.

That is a combination that, at least in this extreme form, has never been seen before. Moreover, and as my exercise from last summer indicates, we can essentially no longer operate without it. I Google-know every day, and I'm sure you do too. But partly as a result, Google-knowing is increasingly swamping other ways of knowing. We treat it as more valuable, more natural, than other kinds of knowledge. That's important, because as we'll see, the human mind has evolved to be receptive to information in certain environments. As a result, we

tend to trust our receptive abilities automatically. That makes sense in all sorts of cases, especially when we are talking about the sensesâseeing, hearing etc. The problem is that Google-knowing really shouldn't be like that; as the

New Yorker

cartoon implies, we shouldn't trust it as a matter of course.

Being Receptive: Downloading Facts

You want to sort the good apples from the bad. Someone gives you a device and tells you to use it to do the sorting. If the device is reliable, then most of the apples you sort into the good pile will, in fact, be good. And this will be the case whether you possess any recognizable evidence to think it is so or not. As long as the device really does its job, it will give you useful information about apples whether or not you have any idea about its track record, or about how it is made, or even if you can't tell a good apple from a pear, or a hole in the ground.

We all need good apple-sorting devices, and not just to sort apples. If you want to find food and avoid predators, which every organism does, you need a way to sort the good (true) information from the bad (false)âand to do so quickly, mechanically and reliably. Call this

being receptive

. When we know in this way, we are reliably tracking the good apples.

Being receptive is a matter of “taking in” the facts. We are being receptive when we open our eyes in the morning and see the alarm clock, when we smell the coffee, when we remember we are late. As we move about, we “download” a tremendous amount of raw dataâdata that is processed into information by our sensory and neural systems. This information represents the

world around us. And if our visual system, for example, is working as it should, and our representation of the world is accurateâif we see things as they areâthen we come to know.

Receptive knowledge isn't “intellectual.” It is how dogs, dolphins and babies know. To have this sort of knowledge, you don't have to know that you know, or even be able to spell the word “knowledge” (or know that it is a word)âalthough if you do, that's okay too.

Receptive states of mind

aim to track the organism's environment, and they are causally connected to the organism's stimuli and behavior. In human animals, we might call these states beliefs, and say that human beliefs can be true or false.

So, knowing by being receptive is something we have in common with other animals, and it is clear we need such an idea to explain how animals (including us) get around in the world. When we explain, for example, why a particular species can protect their nests by leading predators away, we assume they can reliably spot predators.

1

We take them to have the capacity to accurately recognize features of their environment (“predator!”) in a non-accidental way. So the following seems like a reasonable hypothesis: having representational mechanisms that stably track the environment is more adaptive than having mechanisms that only work on Tuesday and Thursdays.

This kind of explanation is what biologists call a “just-so” story. It assumes that behavior that contributes to fitness makes informational demands on a species, and that species' representational capacities were, at least in most cases, selected to play that role.

2

But this story's assumptions are widely held. It leaves us with a pretty clear picture: for purposes of describing animal

and human cognition, we need to think of organisms as having the capacity to know about the world by being

reliably receptive

to their environment, to act as reliable downloaders.

3

Here's the crucial point for our purposes: an organism's default attitude toward its receptive capacitiesâlike vision or memoryâis

trust

. And that makes sense. Even though we know, for example, that our eyesight and hearing can and do mislead us, perception is simply indispensable for getting around in the world. We can't survive without it. Receptive thought is also non-reflective. We don't think about it. That is because ordinarily, most of our receptive processes tick along under the surface of conscious attention. They don't require active effort. This is most obvious in the case of vision or hearing: as you drive down the road to work, along a route you've traveled many times, you are absorbing information about the environment and putting it into immediate action. As we say, much of this happens on autopilot. The processes involved are reliable in most ordinary circumstances, which is why most of us can do something dangerous like drive a car without a major mishap. Of course, each of these processes is itself composed of highly complex sub-processes, and each of those is composed of still more moving parts, most of which do their jobs without our conscious effort. In normal operations, for example, our brain weeds out what isn't coherent with our prior experiences, feelings and what else we think we know. This happens on various levels. At the most basic one, weâagain, unconsciouslyâtend to compare the delivery of our senses, and we reject the information we are receiving if it doesn't match.

This sort of automatic filtering that accompanies our receptive

states of mind is described by Daniel Kahneman and other researchers as the product of “system 1” cognitive processes. System 1 information processing is automatic and unconscious, without reflective awareness. It includes not only quick situational assessment but also automatic monitoring and inference. Among the jobs of system 1 are “distinguishing the surprising from the normal,” making quick inferences from limited data and integrating current experience into a coherent (or what seems like a coherent) story.

4

In many everyday circumstances, this sort of unconscious filteringâcoherence and incoherence detectionâis an important factor in determining whether our belief-forming practices are reliable. Think again about driving your car to work. Part of what allows you to navigate the various obstacles is not only that your sensory processes are operating effectively to track the facts, but that your coherence filters are working to weed out what is irrelevant and make quick sense of what is.

Yet the very same “fast thinking” processes that help us navigate our environment also lead us into making predictable and systematic errors. System 1, so to speak, “looks” for coherence in the world, looks for it to make sense, even when it has very limited information. That's why people are so quick to jump to conclusions. Consider:

How many animals of each kind did Moses take into the ark?

Ask someone this question out of the blue (it is often called the “Moses Illusion”) and most won't be able to spot what is wrong with itânamely, that it was Noah, not Moses, who supposedly built the ark. Our fast system 1 thinking expects something biblical given the context, and “Moses” fits that expectation: it coheres with our expectations

well enough

for it

to slip by.

5

Something similar can happen even on a basic perceptual level; we can fail to perceive what is really there because we selectively attend to some features of our environment and not others. In a famous experiment, researchers Christopher Chabris and Daniel Simons asked people to watch a short video of six people passing a basketball around.

6

Subjects were asked to count how many passes the people made. During the video, a person in a gorilla suit walks into the middle of the screen, beats its chest, and then leavesâsomething you'd think people would notice. But in fact, half of the people asked to count the passes missed the gorilla entirely.

So, the “fast” receptive processes we treat with default trust

are

reliable in certain circumstances, but they are definitely

not

reliable in all. This is a lesson we need to remember about the cognitive processing we use as we surf the Internet. Our ways of receiving information onlineâGoogle-knowingâare already taking on the hallmarks of receptivity. We are already treating it more like perception. Three simple facts suggest this. First, as the last section illustrated, Google-knowing is quickly starting to feel indispensable. It is our go-to way of forming beliefs about the world. Second, most Google-knowing is already fast. By that, I don't just mean that our searches are fastâalthough that is true; if you have a reasonable connection, searches on major engines like Bing and Google deliver results in less than a second. What I mean is that when you look up something on your phone, the information you get isn't the result of much effort on your part. You are engaging quick, relatively non-reflective cognitive processes. In other words, when we access information online, when we try to “Google-know,” we engage in an activity that is composed of a host of smaller cognitive processes

ticking along beneath the surface of attention. Third, and as a result of the first two points, we often adopt an attitude of default trust toward digitally acquired information. It therefore tends to swamp other ways of knowing; we pay attention to it more.

That is not surprising. Google-knowing is often (although not always) fast and easy. If you consult a roughly reliable source (like Wikipedia) and engage cognitive processes that are generally reliable in that specific context, then you are being receptive to the facts out there in the world. You are tracking what is trueâand that is what being a receptive knower is all about. You may not be able to explain why that particular bit of information is true; you may not have made a study of whether the source is really reliable; but you are learning. So, can't we still say that you are knowing in one important sense?

We can. And we do. But Google-knowing is

knowing

only if you consult a reliable source and your unconscious brain is working the way you'd consciously like it to.

If.

There, as always, is the rub.

The day following the bombing of the Boston Marathon in April 2013, social media was clogged with posts of a man in a red shirt holding a wounded woman. The picture was tragic, and the posts made it more so: they told us that the man had planned to propose to the woman when she finished the marathonâuntil the bomb went off. Hundreds of thousands of people reposted and tweeted the story, often contributing moving comments of their own.

The story, however, proved to be false. The man had not been

planning to propose to the woman. They weren't even acquainted. Nor was it true, as was widely reported even in the “mainstream” media (I heard it on my local NPR station the day of the bombing), that the authorities had purposefully shut down cell phone service in Boston (the system simply was flooded with too much traffic). These were rumors, circulating at the speed of tweet.

Rumors like this are also examples of the widely discussed phenomenon of

information cascades

âa phenomenon to which the Internet and social media are particularly susceptible.

7

Information cascades happen when people post or otherwise voice their opinions in a sequence. If the first expressions of opinion form a pattern, then this fact alone can begin to outweigh or alter later opinions. People later in the sequence tend to follow the crowd more than their own private evidence. The mere fact that so many people prior have voiced a particular opinionâespecially if they are in some sense within your social circleâthe more likely it is that you'll go with that opinion too, or at least give it more weight. Social scientists (and advertising executives) who have studied this phenomenon have used it to explain not only how information often moves around the Internet, but how and why songs and YouTube videos become popular. The more people have “liked” a video, the greater the chance even more people will like it, and pretty soon you end up with “Gangnam Style” and “What Does the Fox Say?”

Information cascades are hardly new. The mob mentality has worked its dark magic as long as there have been mobs. That's why my mom used to ask, in response to my whine that “everyone else is [doing, saying, believing] something” that, “If everyone jumped off a bridge, would you jump off too?” Well, hopefully

not, but the history of humanity might suggest otherwise. We not only tend to follow others' actions, we also seem all too willing to go along with what they believe. We trust their testimony, even when we shouldn't.