The Interstellar Age (36 page)

Read The Interstellar Age Online

Authors: Jim Bell

My ASU colleague and

Voyager

historian Stephen Pyne has noted, poignantly, “

Even as they are celebrated for racing forward—to the outer planets, to the heliopause, to interstellar space—many of their most dazzling discoveries were the offshoot of staring back at what they passed in their sling-shot fly-bys. Their trajectory is a triangulation of future and past, or what might be recalibrated as expectation and meditation. The

Voyagers

were special when they

launched. They have become more so thanks to their longevity, the breadth of their discoveries, the cultural payload they carried, and the sheer audacity of their quest.”

“That’s the thing about this mission,” offered Ed Stone, reflecting on

Voyager

’s transition from a planetary to an interstellar mission, “there really hasn’t been an end. All of these encounters and events, are in some sense ‘ends,’ but they’re really not the end

. That’s

really the wonderful thing about

Voyager.”

Postscript: NewSpace

H

UMANS ARE CURRENTLY

controlling about thirty different spacecraft that, together, make up an impressive robotic armada sent out to explore our solar system and beyond. At times we strain to see beyond the turmoil and the swift pace of modern life. We forget to take a moment to look outward and perceive our place in time. We are all living—right now—in an amazing Golden Age of Exploration, of our planet and of our solar system. And if we look closely, in our mind’s eye, we can see the

Voyagers

quietly ushering us to and across the threshold of the Interstellar Age.

How should the future of space exploration unfold? Will NASA and other government space agencies always lead the way? Will upstart private space-related companies (such as SpaceX, Virgin Galactic, Sierra Nevada, and dozens of others) dive into the robotic

space-exploration game, and if so, why? For mineral resources? For fame and glory? To help protect the Earth from rogue asteroids or comets? To settle other worlds? Or will those companies instead focus mostly on providing services like lower-cost rocket launches, adventure-tourism experiences, space-station refueling/resupply, or satellite repair? Those questions are at the forefront of the emerging space industry sector often called NewSpace. Investors large and small are trying to predict which of these businesses, and which of these questions, will drive the future of space-related business and research. And perhaps unbeknown to most people, governments are playing important roles in the increasing privatization of space-related activities. NASA, for example, in their Commercial Orbital Transportation Services and other Commercial Crew & Cargo Programs, has

doled out nearly $2.5 billion of taxpayer funding over the past five years or so to spur the development of many of these “private” initiatives. In many ways, the government is playing a similar role today in the creation of a privately run, civil space program that it played in the early to mid-twentieth century in civil aviation. In the 1920s, for example, the US government was the biggest and most reliable customer for the nascent airline industry, paying out sweet contracts for the delivery of airmail to then-upstart companies with names like TWA, Northwest, and United. Which private space companies being seeded by tax dollars today will emerge as household names and NewSpace industry giants of the twenty-first century?

While missions like

Voyager

were science- and exploration-driven, many NewSpace (and traditional “OldSpace”) companies are of course bottom-line- and profit-driven. Still, there is great potential for collaboration and cross-fertilization. By analogy, fruitful

partnerships have emerged in recent decades between leading environmental and ecological preservation groups and organizations and some parts of the worldwide tourism industry. Nonspecialist individuals and families can now take vacations that also support scientific research projects related to the ecology, archaeology, sociology (and so on) of their destinations. I believe that a similar model could be highly effective for space-related tourism. What many space scientists want most for their research is

access

to the space environment—be it experiments in low gravity, or new measurements from orbital or landed/roving platforms—and an

interested, excited audience

(preferably decision makers at funding agencies, but really anyone genuinely interested is valued) with whom to share their results. If that access is provided by private NewSpace companies, and part of the price is that researchers have to be tour guides and teachers for the paying public sharing the ride, so be it. It’s a model that could work.

I like to imagine an entirely new branch of nerdy but potentially lucrative adventure tourism that could easily, in the not-too-distant future, be built around what I call “manufactured astronomical events.” We’ve all seen photos of the magnificent splendor of a total solar eclipse, for instance, but very few people have actually

seen

a total solar eclipse because they occur only about once every three hundred years in any particular city or region on Earth. But that’s because of the particular geometry of the sun, Earth, and moon for

Earthbound

observers. If we were to take a spaceship to the right places in space, it would be easy to fly the ship through the shadows of the Earth or the moon and re-create the same kind of eclipse experience for those aboard the ship. As another example, there was a lot of hubbub a few years back about people viewing the last transit

of Venus across the disk of the sun until the year 2117. Not necessarily so! Take a ship full of astronomical adventure tourists to the right place in space and at the right time to watch, and—voilà!—there’s a Venus transit as good as any that you’d see from Earth. Many other kinds of “manufactured” celestial events will be possible to create once access to near-Earth (and lunar) space becomes more routine. We could experience Earth-and-moon solar eclipses, transits of Mercury or other planets, flights through active comet tails, flybys and landings on near-Earth asteroids, perhaps even visits to

Voyager

and other ancient spacecraft. Such excursions may never become as routine as airline travel is today, but I believe that the trend will surely be toward safer, more affordable, and more personally meaningful access to space for regular citizens.

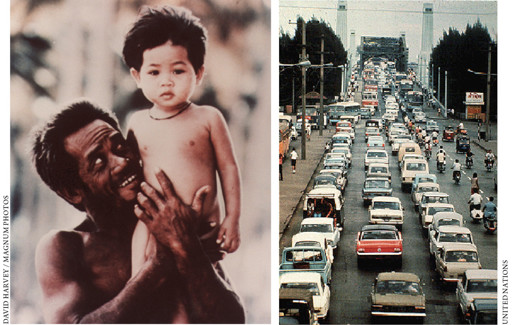

Earth and Moon “Firsts” from Space.

T

OP LEFT

:

Lunar Orbiter I

’s first whole Earth photo from space. T

OP RIGHT

:

Apollo 8

color

Earthrise

photo from lunar orbit.

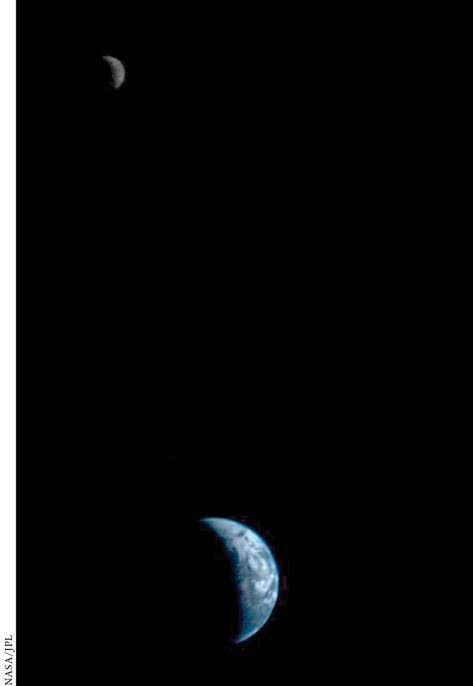

BELOW

: First image of the Earth and Moon together from

Voyager 1

.

Voyager

and the Golden Record.

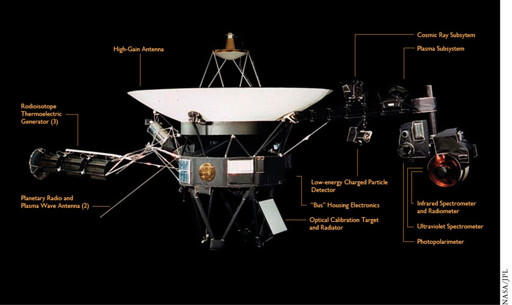

T

OP

: Spacecraft and systems/instruments. L

OWER LEFT

: Close-up of the Golden Record case mounted on the side of the spacecraft bus. L

OWER RIGHT

: Close-up of the first side of the actual record.