Read The Invitation-Only Zone Online

Authors: Robert S. Boynton

The Invitation-Only Zone (3 page)

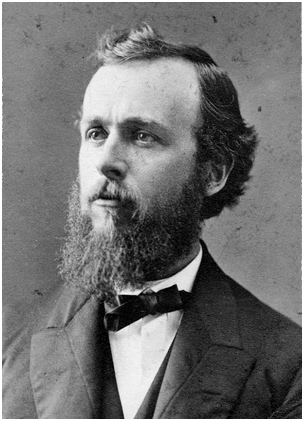

Edward Sylvester Morse

(Wisconsin Historical Society)

Morse escaped the confines of life in provincial Portland by searching for shells on the Maine coast. Portland had a rich history of trade with destinations all over the world, and sailors regularly returned with strange-looking shells, some of which were sold for vast sums. Morse amassed an enormous collection of native New England specimens,

which drew the attention of scholars from around the country. At age seventeen he presented a paper to the Boston Society of Natural History, which named one of his discoveries,

Tympanis morsei

, after him. Word of Morse’s collection spread to Harvard, where Louis Agassiz held the university’s first chair in geology and zoology. The Swiss-born Agassiz was one of the most famous scientists in the

world, having made his reputation by proving that much of the globe was once covered by glaciers. A superb promoter, he convinced New England’s Brahmins to support science and, specifically, to fund the construction of the world’s largest Museum of Comparative Zoology, where he intended to display his specimens. In Morse, Agassiz found a young man with the intelligence and energy to catalogue his

vast holdings; in Agassiz, Morse found a father figure who, unlike his own father, encouraged his scientific work. “There is no better man in the world,” Morse wrote of Agassiz in his journal. Paid twenty-five dollars per month, plus room and board, Morse became one of Agassiz’s assistants, an elite group, destined to become some of America’s foremost natural historians and museum directors. A classically

educated European, Agassiz was as much their mentor as their employer, inducting them into the modern priesthood of science, while also urging them to study history, literature, and philosophy. Conscious that he was the only one in this group without a college degree, Morse became a diligent student, attending lectures on zoology, paleontology, ichthyology, embryology, and comparative anatomy,

while also cataloguing thirty thousand specimens in his first year.

Morse arrived in Cambridge in November 1859, the month Charles Darwin published

On the Origin of Species

. A pastor’s son, Agassiz couldn’t bring himself to replace the biblical creation story with the theory of evolution, and became one of Darwin’s foremost critics. Morse read Darwin’s book with excitement but was careful not

to antagonize his mentor while he considered the validity of Darwin’s revolutionary ideas. By 1873, however, he had fully embraced Darwin. “My chief care must be to avoid that ‘rigidity of mind’ that prevents one from remodeling his opinions,” he wrote. “There is nothing [more] glorious … than the graceful abandoning of one’s position if it be false.” He sent Darwin a paper in which he used his framework

to reclassify brachiopods as worms rather than mollusks. “What a wonderful change it is to an old naturalist to have to look at these ‘shells’ as ‘worms,’” Darwin replied.

Having broken with his mentor, Morse left Harvard and discovered he was such an entertaining speaker that he could earn five thousand dollars a year lecturing on popular science. He illustrated his lectures with detailed sketches,

drawing with both hands simultaneously, a bit of chalk in each.

5

During a San Francisco lecture, he learned that the waters of Japan held dozens of species of brachiopods that were unknown in the United States. In the spring of 1877, Morse boarded the SS

City of Tokio

.

On the evening of June 18, Morse’s ship moored two miles offshore from Yokohama, and the next day he took a rickety boat to the

mainland, rowed by three “immensely strong Japanese” whose “only clothing consisted of a loin cloth,” he wrote in

Japan Day by Day

. He was overwhelmed by the foreignness of the lively city. “About the only familiar features were the ground under our feet and the warm, bright sunshine,” he wrote. Morse brought a letter of introduction to Dr. David Murray, a Rutgers College professor of mathematics

who had been appointed the superintendent of educational affairs for the Japanese Ministry of Education and charged with creating an American-style public school system from grade school through university. Although private academies existed in pre-Meiji Japan, the Sino-centric curriculum was largely restricted to the teachings of Confucius. The Japanese wanted universities comparable to the great

institutions that Europe had taken centuries to build, and they wanted them now. The Ministry of Education received a third of the government’s total budget for the project, and Murray was given two years to get Tokyo University up and running.

Foreigners were forbidden from traveling outside Japan’s designated treaty ports, so the only way for Morse to explore for brachiopods was to get special

permission, which he hoped Murray would help him with. To reach Murray’s office, he rode the recently completed train line eighteen miles to Tokyo University, which had welcomed its first students three weeks before. As the train approached the village of Omori, it traversed two mounds through which the tracks had been laid. A cockleshell dislodged by the digging caught Morse’s eye. “I had studied

too many shell heaps on the coast of Maine not to recognize its character at once,” he wrote. It was a five-thousand-year-old

Arca granosa

.

Murray introduced Morse to several Japanese colleagues with whom he shared his passion for science. They found his excitement contagious, and made an astounding proposal. Would Morse establish a department of zoology and build a museum of natural history

at Tokyo University? In return, they would provide him a biological laboratory, moving expenses, and a professor’s salary of five thousand dollars per year. Darwinism had arrived in Japan during a period of drastic cultural change, and they wanted a Western expert who could explain these foreign ideas.

6

Morse was asked to teach a class on modern scientific methods and give a series of public lectures

on Darwin. Hundreds attended the lectures, and Morse was pleased both by the enormous size of the audience and by its openness to the idea of evolution. “It was delightful to explain the Darwinian theory without running up against theological prejudice, as I often did at home,” he wrote. Not only were the Japanese not Christians, but the Meiji government was hostile to the creed, which it

perceived as a threat to its authority. When Morse argued that “we should not make religion a criterion of investigating the truth of matter,” he no doubt pleased Japan’s bureaucrats and scientists alike.

With Murray’s aid, Morse returned to Omori several weeks later with his students. “I was quite frantic with delight,” he wrote. “We dug with our hands and examined the detritus that had rolled

down and got a large collection of unique forms of pottery, three worked bones, and a curious baked-clay tablet.” In order to cross-date the artifacts with ancient flora, fauna, and fossils, Morse and his students used the modern method of digging one layer at a time, a technique that had never been used before in Japan.

7

Morse’s book

The Shell Mounds of Omori

(1879) was the first published by

the university’s press.

One of the most profound revolutions inspired by Darwin’s

Origin of Species

was in the study of early human history, as the notion of “prehistory,” the time before recorded history, led scholars to use physical remains to chart human development from “savagery” to “civilization,” a hierarchy of cultural advancement Darwin later expanded upon in

The Descent of Man

(1871).

8

After Darwin, scholars who had searched far and wide for disparate clues to human development focused their research on chronicling the successive generations who had inhabited a single place, such as Omori. What Morse found at Omori puzzled him. Among the shells and pottery fragments were broken human bones mixed in with those of animals—not what one might find at a typical burial site. “Large

fragments of the human femur, humerus, radius, ulna, lower jaw, and parietal bone, were found widely scattered in the heap. These were broken in precisely the same manner as the deer bones, either to get them into the cooking-vessel, or for the purpose of extracting the marrow,” he wrote.

9

It was impossible to avoid the conclusion that the people who had once dwelled in Omori had been cannibals.

Judging by the age of the bones, Morse didn’t believe the cannibals were

direct

ancestors of either the Japanese (whom he praised as the “most tranquil and temperate race”) or the indigenous Ainu (who were neither cannibals nor potters). Rather, he concluded, the artifacts had been produced by a pre-Japanese, pre-Ainu tribe of ancient indigenous people.

Morse’s discovery gave birth not only to

modern Japanese anthropology but also to the questions that would obsess the discipline for the next seventy-five years: Who were the Japanese people’s original ancestors? Where did they come from? And how were they related to the fast-modernizing Meiji-era Japanese? Much as Western technology gave the Japanese control over their future, Darwin’s theories provided the tools with which to understand

their past. Like explorers embarking on an expedition to chart a new world, anthropologists were on a quest to create a modern map of Japanese origins.

Morse’s best student was Shogoro Tsuboi, the twenty-two-year-old son of a prominent doctor. Tsuboi grasped the enormity of the revolution reshaping geology, biology, and the social sciences, and formed a study group that spent weekends excavating

near Tokyo University and discussed their findings at evening salons. A cosmopolitan intellectual, Tsuboi studied in London for three years under the great anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor, who used Darwin’s system of classification to divide humanity into racial groups.

10

When Tsuboi returned home, he introduced the new discipline to Japan by publishing in popular journals and lecturing widely

on anthropology and evolutionary theory.

Ryuzo Torii (second from right) and Shogoro Tsuboi (right)

The Western, biological conception of race did not exist in Japan before this period,

11

and Morse’s essay “Traces of an Early Race in Japan” was the first time it was applied to Japan. In pre-Meiji Japan, identity and class distinctions came from the customs, not the blood, one shared with a peer group. For millennia, Asian culture had

been dominated by China, and it was believed that a country’s level of civilization was determined by how far it was from the Chinese emperor. Indeed, Korea interpreted its own proximity to China as evidence that it was more civilized than Japan. In the hands of intellectuals such as Tsuboi, race took on a more biological and scientific significance than ever before.

Tsuboi was particularly eager

to use historical anthropology to investigate the origins of the Japanese. Employing Darwin’s schema, he reasoned that cultures, like species, develop unevenly, with the vigorous and adaptive jumping ahead and the isolated and recalcitrant lagging behind. He observed that European archaeologists of the day drew analogies between tools produced by Stone Age people and implements used by contemporary

aborigines in New Guinea—the implication being that one could detect traces of ancient civilizations in the amber of surviving primitive cultures. If Western scholars could draw direct analogies of this sort, why couldn’t Japanese scholars do so as well? It irked him that Morse, author of the much-resented cannibal hypothesis, was credited as the founder of Japanese anthropology, and going

forward Tsuboi felt it should be a strictly Japanese affair. When he became the university’s first full professor of anthropology, he removed Morse’s Omori shell mounds from the museum to make room for “far more valuable specimens” collected by Japanese researchers. Tsuboi envisioned Japanese anthropology as a self-sufficient branch of social science, with Japanese scholars studying the history of

the Japanese people in Japan. “Our research materials are placed in our immediate vicinity,” he wrote. “We are living in an anthropological museum.”