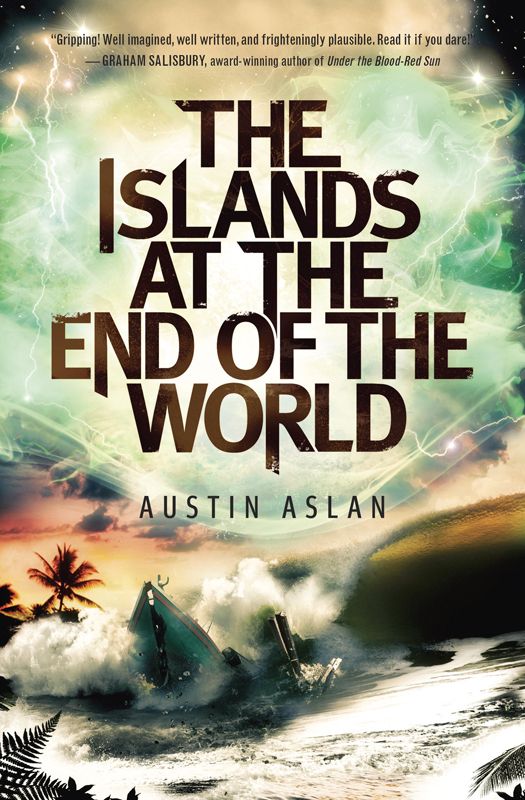

The Islands at the End of the World

Read The Islands at the End of the World Online

Authors: Austin Aslan

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Text copyright © 2014 by Austin Aslan

Jacket art copyright © 2014 by Tom Sanderson

Map illustration copyright © 2014 by Joe LeMonier

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Wendy Lamb Books, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

Wendy Lamb Books and the colophon are trademarks of Random House LLC.

The author would like to thank the Tad James Companies for their gracious permission to use the translation of the ho`opuka chant that appears on

this page

,

this page

, and

this page

.

Visit us on the Web!

randomhouse.com/teens

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at

RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Aslan, Austin.

The islands at the end of the world / Austin Aslan. — First edition.

pages cm

Summary: Stranded in Honolulu when a strange cloud causes a worldwide electronics failure, sixteen-year-old Leilani and her father must make their way home to Hilo amid escalating perils, including her severe epilepsy.

ISBN 978-0-385-74402-7 (trade) — ISBN 978-0-375-99145-5 (lib. bdg.) —

ISBN 978-0-385-37421-7 (ebook) — ISBN 978-0-385-74403-4 (pbk.) [1. Science fiction.

2. Refugees—Fiction. 3. Epilepsy—Fiction. 4. Fathers and daughters—Fiction.

5. Extraterrestrial beings—Fiction. 6. Hawaii—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.A83744Isl 2014

[Fic]—dc23

2013041281

Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

To my wife, Clare,

and her dad, Jerry,

the best father-daughter team I have ever known

E iho ana o luna

E pi`i ana o lalo

E hui ana na moku

E ku an aka paia

That which is above will come down

That which is below will rise up

The islands shall unite

The walls shall stand firm.

—

Ancient Hawaiian Prophecy

S

UNDAY

, A

PRIL

26

They’ve been getting bigger all evening. This one might be too big, but I can’t be choosy. Dad’s waiting on the bluff, arms crossed. I lie down on my board and drive my arms through the water.

No sweat. Just relax

.

“Geev’um, Lei!” shouts Tami.

The wave is coming like a train. I paddle fiercely, though the life vest rubs my upper arms raw.

The wave pulls on me, hungry. For once my timing is perfect. The wave surges under me; I catch the break and spring up on the board.

Two seniors on their boards shoot me the stink-eye as I wobble past. One snickers. The life jacket feels like a straitjacket. I nearly tumble backward off the board but catch my balance.

I kick my back leg to the left and angle the board to the right, feeling a rush of speed. I dart between a

keiki

body-boarder and a lazy green sea turtle, finally sinking back into the water as the wave dies. I turn to salute Tami, who’s bobbing out past the first breaks. Her honey-blond corkscrews bounce even when wet.

“Next week!” I shout.

“Nice one, girl!” she yells back. “Aloha! Enjoy the north shore!”

All next week I’ll be in Honolulu, on the island of O`ahu, with Dad, and he’s promised me some time at Banzai Pipeline on the north shore. Just to watch. Only the pros tackle those waves.

I sweep my long, soaked hair out of my face as I clamber over the rocks tumbling in the breaking surf. O`ahu. Anxiety flutters through me. I’m surfing to forget the EKGs and MRIs and OMGs that I’ll be facing.

You just nailed one of your biggest waves ever. Focus on that

.

I trudge up the steep stairs to the road, using both arms to carry my longboard. Dad takes it from me as I reach the car, offers me a high five. “Way to end the day.”

I smile and clap his waiting hand. “Thanks.”

He leans against our purple car, a

MAY THE FOREST BE WITH YOU

bumper sticker broadcasting his dorkiness. We have the only hybrid vehicle in a long row of big trucks at the end of the cliff. Come to think of it, I can’t remember the last hybrid car I saw in Hilo—or on the entire Big Island of Hawai`i.

“That was totally gnarly, but I’m still annoyed you made me wait so long.” He passes me a towel after he places the board on the car’s rack.

“Dad,” I groan. A couple of Hawaiian girls from school walk past us on the steep road, giving me a hard look. I turn away as I slip out of my vest. “No one asked you to babysit me. And ‘gnarly’? Wrong century.”

Dad runs a hand through his Malibu-certified sandy hair. His grin widens. “Whoa. Sorry, dudette.” He

intentionally

raised his voice so those girls would hear, didn’t he? Drives me nuts.

“You more relaxed?” He ties the board down for me.

No

. But I nod. A light drizzle begins to fall. Rain on the Hilo side of the Big Island is as abundant as sun in a desert. It’s like background noise. I keep drying off as I sit in the car. I eye the steering wheel. I’m sixteen, finally old enough to drive. The doctor hasn’t signed off on me getting my license yet, but I manage to get behind the wheel now and then.

“Can I drive?”

“Haven’t you done enough damage to Grandpa’s clutch?”

Ha, ha

.

I toss my towel in the back and look in the mirror. Long black hair. Oval face with high cheeks. My eyes are hazel, my complexion is … too light. I’m almost as white as Dad. Pretty, I guess, if you listen to my parents. If I ever get a boyfriend, maybe I’ll believe it.

Dad performs one of his infamous fifty-point turns to get us facing the right direction on the narrow road. I glance

down from the cliff at the strip of rocky beach. The waves are getting big.

Tami better wrap it up

. We pull away and the hard-eyed local girls study our car as we roll past. I know one of them—Aleka. She’s always staring me down. I sink into my seat.

“You were good out there,” Dad says. “It’s coming to you pretty naturally now.”

“Dad, being a haole around here pretty much sucks—especially a haole with head issues—”

“You’re

hapa

,” he corrects me, feigning shock. “You’re only half white, hon.

I’m

the only haole here. Your mother and grandparents count for something, don’t they?”