The Italian Boy (5 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

He told the coroner’s court that he had accidentally met Bishop in Covent Garden on the Saturday morning, and he denied being in the Fortune of War altogether. Warned by vestry clerk James Corder, “Take care—the pot-boy is present. Don’t you recollect having any egg-hot at the Fortune of War that morning?” Shields immediately admitted that the meeting in Covent Garden on the Saturday was a lie—at which a murmur of astonishment passed around the upstairs room at the Unicorn pub. Shields claimed that when they reached King’s College, he had stood outside while Bishop, May, and Williams took the hamper into the dissecting room; but Hill had already told the coroner’s court of the friendly conversation he had had with Shields. When asked if he knew anything about the death of the boy, Shields replied, “Bishop said that the body was got from the ground, and that he knew where it was got from. He smiled as he said so, saying that if he were brought before the jury, he would give them ease about it.”

After Shields stepped down, Bishop was brought forward and, with James Corder recording every word, said: “I cannot account for the death of the deceased. I dug the body out of the grave. The reason why I decline to say the grave I took it out of is that there were two watchmen in the ground, and they intrusted me, and being men of family, I don’t want to deceive them. I don’t think I can say any more. I took it for sale to Guy’s Hospital, and as they did not want it, I left it there all night and part of the next day. And then I removed it to the King’s College. That is all I can say about it. I mean to say that this is the truth. I shall certainly keep it a secret where I got the body. I know nothing as to how it died.” The coroner was not impressed by Bishop’s explanation and warned him that a higher court was likely to interrogate him far more closely. The coroner said it was impossible for someone to be in possession of a body that was almost warm without knowing what had happened to it. Facetious in the face of pomposity, Bishop replied that it was impossible for it to have been warm—it had passed a night at Guy’s Hospital. Bishop offered to sign his statement, though in law he was not obliged to sign; by withholding his signature, he would have been able to make subtle alterations to his version of events, to counteract any new information that might come to light during the investigation. But he chose to sign; it looked more honest. He had not created a good impression in court. A series of mocking, sardonic interjections had backfired on him. When William Hill had been giving evidence, Hill had been asked by the magistrate, “Is it customary for persons in your station to receive such presents?” with regard to the tip that Bishop had promised him. Bishop had called out, “He gets many a guinea in that way!” And Bishop had laughed when Hill told the court of his worries about the body’s freshness; the body snatcher had sneered across the courtroom, “The fact is, you are not in the habit of seeing fresh Subjects and you don’t know anything about it!”

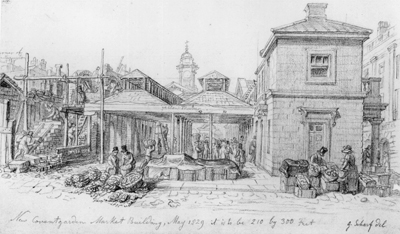

Stallholders selling fruit and vegetables as Covent Garden’s new market building approaches completion, in 1829, sketched by artist George Scharf

Next, it was James May’s turn to speak. He confidently explained that he wished to tell the court everything he knew—he would speak only the truth. “I live at 4 Dorset Street, Newington. I went into the country last Sunday week and returned on the following Wednesday evening. I brought home a couple of Subjects with me. I took them to Mr Grainger’s in Webb Street the same evening, and on the following morning, which was Thursday, I removed them to Mr Davis at Guy’s and after receiving the money, went away. I went to the Fortune of War in Smithfield and I stayed there, I dare say, for two or three hours. Between four and five o’clock, to the best of my recollection, I went to Nag’s Head Court, Golden Lane, and there I stopped with a female till eleven or twelve the next day, Friday. From Golden Lane I went to the Fortune of War again, and there I stopped drinking till six o’clock, or half past. Williams and Bishop both came in there. They asked me if I would stand any thing to drink, which I did. Bishop then called me out and asked me where I could get the best price for Things. I told him where I had sold two at Guy’s and he told me he had got a good Subject, and he had been offered eight guineas for it. I told him I could get more for it. He said all I could get over nine guineas I might have for myself, and I agreed to it. We went from there to the Old Bailey and we had some tea at the watering house in the Old Bailey, leaving Williams at the Fortune of War. After we had tea we called a chariot off the stand and drove to Bishop’s house. When we came there, Bishop showed me the lad in a box or trunk. I then put it into a sack and took it to the chariot myself, and took it from thence to Mr Davis at Guy’s. Mr Davis said, ‘You know, James, I cannot take it, because I took two off you yesterday, and I have not got [student] names enough down for one, or else I would.’ I asked him if I might leave it there that night and he said, ‘Certainly.’ Bishop then desired Mr Davis not to let any person have it but himself, for it was his own Subject, which Mr Davis said he would not, and told his man James not to let any person have it besides himself. I told Mr Davis not to let it go until I came as well, for I should be money out of pocket if it went before I came. I went home that evening, where I slept, and in the morning I went to Mr Davis and had not been there many minutes before Bishop came in, and Shields with a hamper, and took it from thence to King’s College, and there I was taken into custody.” May was happy to sign his statement. There was no mention of the clothes buying and rum drinking in Field Lane and West Street. But he did own up to the selling of the teeth: “I admit all that, and what does it amount to? I did use the brad awl to extract the teeth from the boy, and that was in the regular way of business, and in doing so, I wounded my hand slightly—there is nothing very wonderful in that.”

For his part, Thomas Williams claimed that he had gone along to King’s only to see what the new building was like—perhaps not such an unreasonable claim: the Robert Smirke–designed college was considered a glorious new addition to the capital. “I live at Number 3 Nova Scotia Gardens and am a glass-blower. In the first place, I met with Bishop last Saturday morning in Long Lane, Smithfield. I asked him where he was going. He said he was going to King’s College. We then went to the Fortune of War public house. Instead of going to King’s College, we went to Guy’s Hospital and he came out of there and went to the King’s College. Then May and the porter met us against the gate, then Bishop went in, and I asked him to let me go in with him. A porter took a basket from the Fortune of War to Guy’s Hospital, and I helped him part of the way with it. That is all I have got to say.” Williams declined to sign this slightly different version of events.

Richard Partridge and George Beaman explained to the coroner and his jury their findings at the postmortem. Although they disagreed on the details, both men found that death had been caused by a blow to the back of the neck, probably with a stick or some other implement. The wound on the boy’s temple was superficial, they agreed.

* * *

At half past ten

on the evening of Thursday, 10 November, the foreman of the coroner’s jury returned the verdict: “We find a verdict of wilful murder against some person or persons unknown, and the jury beg to add to the above verdict that the evidence produced before them has excited very strong suspicion in their minds against the prisoners Bishop and Williams, and that they trust that a strict inquiry will be made into the case by the police magistrates.” No mention was made of May.

A juror stood up to praise Superintendent Thomas; the jury foreman added his praise for the policeman and also praised vestry clerk James Corder; the coroner praised Corder, and Corder thanked the jury and praised the coroner.

* * *

The apparent similarities

to the Burke and Hare murders, and the deep embarrassment that case had caused the medical and legal professions, had prompted Home Secretary Viscount Melbourne to request James Corder to forward the verdict and a report of the coroner’s hearing to him as quickly as possible. This Corder did, at eleven o’clock at night in a hand-delivered letter, apologizing for disturbing his lordship at such a late hour but saying that his urgency was due to the fact that “the enquiry into the present case has been the means of eliciting the fact that several boys of a similar age to the deceased have recently been missed by their friends, and there is too much ground for justifying the conclusion that they have, with him, been the victims of a horrid system carried on for some time past by wretches whose business it is to supply the hospitals.”

11

Outside Corder’s office, in the dark and the freezing fog of November, beneath the stalls and in among the fruit and vegetable baskets of Covent Garden’s market building, some hundred or so destitute boys and girls were bedding down for the night.

TWO

Persons Unknown

John Bishop had been a resurrection man for twelve years; James May had started to disturb the dead in 1825, acquiring the nickname Jack Stirabout (slang for “prison,” after the maize and oatmeal staple jail diet) and a string of convictions for grave robbery; Thomas Williams was new to the trade, having recently emerged from a prison sentence for theft; Michael Shields was a familiar face around the graveyards of central London. Resurrection was a revolting but potentially highly lucrative trade, with earnings way beyond those of even the most highly skilled worker. In 1831, a silk weaver in the East End of London could earn as little as five shillings a week working a twelve-hour day, six days a week.

1

A well-paid manservant to a wealthy London household could expect to earn a guinea a week, which was also the starting wage for the first constables recruited to the Metropolitan “New” Police force in 1829. By contrast, a disinterred body could bring in between eight and twenty guineas, depending on its freshness and on how many Things were being hawked around London’s four hospital medical schools and seventeen private anatomy schools in any given week.

2

It was a speculative trade, and John Bishop himself missed out on more than one occasion by failing to procure promptly a corpse for a surgeon who went ahead and bought one from a rival who had delivered more quickly. There were periodic gluts as well as lulls: the work was largely seasonal, since the hospital schools ran courses from October to April, though many private lecturers held summer classes.

Male corpses were more highly prized than female because they offered greater scope for the study of musculature, while a fresh, well-developed limb could be worth more than a whole body that was on the verge of putrefaction. Other “offcuts”—a woman’s scalp with long, thick hair attached; unchipped teeth (“grinders”), either singly or as whole sets—were profitable sidelines for the resurrectionist as the living paid well to patch themselves up from parts of the dead. High infant mortality resulted in a brisk trade in children, either as “big smalls,” “smalls,” or fetuses. Specialty corpses achieved higher-than-average prices: in the autumn of 1827, when a young female inmate of an insane asylum succumbed at last to a long illness, William Davis, a member of the notorious Spitalfields Gang of snatchers, was offered twenty guineas by surgeons keen to anatomize her brain; but Davis was arrested by a parish watchman as he was digging up the corpse in a private burial ground in Golden Lane.

3

There were around eight hundred medical students in London in 1831, of whom five hundred dissected corpses as part of their anatomical education; each student was said to require three bodies during his sixteen-month training—two for learning anatomy, one for learning operating techniques.

4

The only legal supply of flesh came from the gallows, with the corpses of those executed for murder being made available to the nation’s surgeons. But the number of murderers being executed was far too low to meet the needs of an expanding, research-hungry medical profession. Death sentences for any crime were increasingly unlikely to be carried out as the Bloody Code of the eighteenth century—a series of legal enactments that introduced capital punishment for a wide range of petty theft and antisocial acts—was diminished by wave upon wave of legislation.

5

However, the concurrent rise in arrests and convictions guaranteed that the number of those executed held steady. Thus, while 350 death sentences were passed in England and Wales in 1805, only 68 people were executed (10 for murder); in 1831, 1,601 people were condemned to death, yet only 52 were executed (12 for murder).

6

And so the anatomists and their students relied on the “snatchers,” “grabs,” “lifters,” “exhumators,” or “resurgam homos” to make up the numbers.

Digging up the dead in overcrowded city graveyards was physically arduous, but an exhumation could be completed in as little as half an hour by the well-practiced. Resurrection men would also travel to outlying villages to retrieve corpses. Just as livestock, vegetables, herbs, and milk were imported daily into the capital and touted around the streets by itinerant sellers, the country dead were regularly ferried into town on covered “go-carts.” A network of informers passed details to the London gangs of an impending death or recent burial in villages and hamlets, with corrupt sextons, gravediggers, undertakers, and local officials taking a cut of the sale price. The Wednesday before his arrest, James May had just got back from the country, where he had been disinterring the rural dead; on the Thursday, he had failed to make a sale of his two dead rustics at Grainger’s, but Guy’s took them off his hands for ten guineas each.