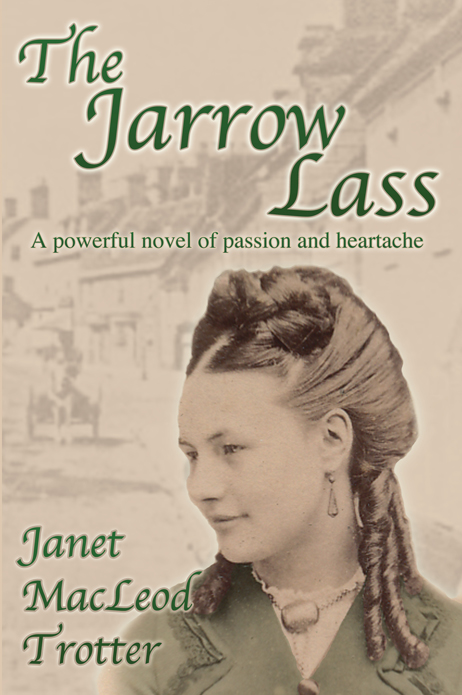

The Jarrow Lass

Authors: Janet MacLeod Trotter

The Jarrow Lass

The compelling first novel in the Jarrow Trilogy

Janet MacLeod Trotter

Copyright © Janet MacLeod Trotter, 2001

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the written permission of the publisher.

Published by MacLeod Trotter Books

First eBook edition: 2011

ISBN 978-1-908359-00-1

For my special, special daughter Amy - with all my love

***

Many thanks to the welcoming members of The Jarrow & Hebburn Local History Society for all their kindness, help and encouragement.

***

Janet MacLeod Trotter was brought up in the North East of England with her four brothers, by Scottish parents. She is a best-selling author of 15 novels, including the hugely popular Jarrow Trilogy, and a childhood memoir, BEATLES & CHIEFS, which was featured on BBC Radio Four. Her novel, THE HUNGRY HILLS, gained her a place on the shortlist of The Sunday Times' Young Writers' Award, and the TEA PLANTER'S LASS was longlisted for the RNA Romantic Novel Award. A graduate of Edinburgh University, she has been editor of the Clan MacLeod Magazine, a columnist on the Newcastle Journal and has had numerous short stories published in women's magazines. She lives in the North of England with her husband, daughter and son. Find out more about Janet and her other popular novels at:

www.janetmacleodtrotter.com

Also by Janet MacLeod Trotter

Historical:

The Beltane Fires

The Hungry Hills

The Darkening Skies

The Suffragette

Never Stand Alone

Chasing the Dream

For Love & Glory

Child of Jarrow

Return to Jarrow

A Crimson Dawn

A Handful of Stars

The Tea Planter's Lass

Mystery:

The Vanishing of Ruth

Teenage:

Love Games

Non Fiction:

Beatles & Chiefs

Praise for Janet MacLeod Trotter's novels

âA passionate and dramatic story that definitely warrants a box of tissues by the bedside'

Worcester Evening News

âA gritty, heartrending and impassioned drama'

Newcastle Journal

âA tough, compelling and ultimately satisfying novel... another classy, irresistible read'

Sunderland Echo

âTruly a novel for saga lovers, weaving together the lives of many characters with compassion and affection'

Northern Echo

Chapter 1

1861 - Lamesley, County Durham

Rose clung on to her grandmother's gnarled hand, terrified of being swept away by a sea of dresses and buffeting legs. A cannon exploded deafeningly, and the tiny girl screamed and burst into tears.

Her grandmother swung her up into comforting arms and grinned at her toothlessly from under a huge faded bonnet.

âHush, hush!' she soothed. âYou mustn't cry on Miss Isabella's weddin' day! I'll treat you to a twist of barley sugar if you stop your wailin'. Look, see how grand they all look? Isn't it a sight to warm the heart? And look at them horses - gleamin' like marble. No one keeps a stable like Lord Ravensworth.'

She pointed with a rough, calloused finger at the procession of horse-drawn carriages trotting smartly through the crowds of villagers and estate workers, snaking their way out of the wooded hillside.

Rose now gripped her grandmother's neck tightly; convinced the horses would sweep them away. Why was everyone cheering and waving so happily when her ears were hurting from so much noise? The women were turned out in their best bonnets and print dresses, and men wore their Sunday breeches. Bigger children than she were running around shouting and knocking each other over in their eagerness to see the grand gentry from Ravensworth Castle, that mysterious cluster of towers gleaming over the newly budding trees.

Rose felt she had been waiting there for ever and wanted it all to be over. They saw smartly dressed soldiers in scarlet tunics clatter into the church, their swords flashing in the spring sunshine.

âShe's marryin' an officer,' Granny shouted over the raucous noise of a military band, pointing at a tall man with thick side whiskers. But Rose buried her face in the old woman's shoulder and refused to look at these stern men, who Granny said had fought against the Russian Bear in the Crimea.

Granny was full of stories for anyone with half an ear to listen. She knew everything about these godlike people, for she had worked at the magical castle on the hill since she was a girl. Rose loved to sit on her knee and listen to her talk of this place of many bedrooms and countless fires to lay, of beautiful dresses and important people who spent their days banqueting or riding the hills of County Durham.

âI was there when the Duke came to stay,' Granny would say in a voice full of reverence. âHe saved us all from the French bogeyman.' Rose was particularly scared of the bogeyman, who Granny said would catch naughty children if they did not do as they were told. âThey feasted for days when the Duke of Wellington came to stay,' Granny would cackle. âRode all over the county feastin' - and back at the dead o' night by flamin' torchlight!'

All around them, cheers went up as the carriages stopped outside the squat-towered church of Lamesley and a footman rushed to open the door of the first carriage. An elderly man in a tall black hat stepped down and Granny cried out, âGod bless you, Lord Ravensworth!'

Rose waited for the man to call back to her grandmother, but everyone was making such a noise, he did not seem to hear and did not reply. Then the small girl caught her breath and stared at the beautiful lady who climbed out next. She was a shimmer of white satin and silk, her billowing skirts catching in the April breeze, flounces of lace and ribbons fluttering like butterfly wings. Just then, a shaft of sunlight broke from behind the racing clouds and set the headdress of orange blossom aglow.

Rose gaped open-mouthed at the heavenly vision, her fears forgotten. She yearned to see the face of this angel, but it was hidden behind a gossamer veil.

Granny grew garrulous. âBonny, bonny bride!' she kept repeating, wiping away tears of emotion. âYour mammy could have been workin' for the likes of the mistress, if she'd listened to my advice. A good job she could have had in the kitchens, just like me. I would have put a word in for her. But no, your mammy knew better. She lost her head over that Irishman McConnell. Now she's feedin' pigs and diggin' leeks in that terrible place - like the jaws of Hell. You could've been runnin' all summer with the village children,' Granny ranted, âbreathin' in God's fresh air, instead of all that smoke and filth in the town. I wish I could keep you here wi' me in the almshouse for ever, but it's not allowed. Cryin' shame!' But no one around her was listening.

Rose was straining to see where the angel had gone, and wanted to follow. She didn't like all her grandmother's talk of the filthy town and the jaws of Hell. She knew she had been sent to stay in the village because there was fever in the town, and fever was bad because it could kill children between sundown and sunrise. Rose wriggled out of her grandmother's hold easily, for the old woman was tiring of carrying her, and pushed her way through the forest of legs to the church wall. Someone lifted her up so she could see the entrance, but the beautiful lady had disappeared and the doors were firmly shut.

Just when she was growing bored with waiting, the church bells erupted in a deafening peal and the church doors flew open. The angel appeared on the arm of the stern soldier and this time her face was visible. For a brief moment, the face of the angel looked up, noticed Rose sitting on the wall, and smiled. Rose felt bathed in warmth like the heat from the kitchen fire. It was a feeling she would never forget. She knew she could never now be taken away by the fever, because she was friends with an angel and this figure in dazzling white would always protect her. For the first time in her young life, Rose McConnell felt brave.

As the band struck up and the villagers threw handfuls of rice on the newly wedded couple for good luck, she waved and clapped from her perch on the wall. Older children ran behind the bridal carriage, scrabbling in the mud to pick up the coins that the groom threw to them from the open window. Rose gazed after the procession until it was lost once more in the trees, and would have sat there all day if Granny had not ordered her down.

The villagers set about celebrating with races in the fields for the children, and much drinking of beer at old Ravensworth Arms, the village coaching inn. Rose sucked her sugar stick and drank milk that was still warm from the cow, content with her new surroundings. She had almost forgotten what home looked like: a blackened wall under a pall of grey smoke, hens perched on a steaming midden, windows too filthy to see through. Here, as daylight waned, she could see stars pricking a velvet sky. Never had she seen such brightness in a night sky.

âWhat's that?' she asked Granny sleepily as she was carried home on the old woman's stooped back.

âWhy, lass, have you never seen the moon before?' Granny cried in amazement.

âWe don't have one in Jarrow,' Rose yawned.

âIt's there,' Granny snorted, âyou just can't see it for all that smoke.'

âLike an angel's face,' Rose murmured, her eyelids heavy. As she fell asleep on her grandmother's back, the moon became confused in her groggy mind with the smiling face of the angel bride. It would always be there to protect her even if she could not see it, Rose thought. Granny had promised it was so.

For young as she was, Rose was already aware that she would need protection when she returned to the land of smoke and fever that was her home.

Chapter 2

1872 - Jarrow, Tyneside

âWell, one of you will have to go!' Mrs McConnell snapped, her nerves frayed at her daughters' bickering. âYour da promised those cabbages to Mrs McMuIlen and she's a dozen hungry lads to feed. Maggie, get yourself over there sharp if you don't want to feel the back of my hand.'

âWhy can't Lizzie or Rose go?' Maggie protested, beginning to cough. Rose noticed how her sister always began coughing like a consumptive when she did not want to do something. It made their mother fret and forget about being cross with her.

âI went over to the cottages yesterday,' Lizzie answered. âIt's my turn to feed the hens.' She went back to her sewing. Rose knew how her other sister hated to get her hands dirty at all and was always complaining about the amount of muck around their parents' smallholding. But they were luckier than most in their part of Jarrow. Their father helped out at a local blacksmith's as well as tending the plot of land he rented from the tenant farmer. They had regular food on the table and did not have to take in lodgers when there was a slump in the shipyards. Yet when the dock gates of mighty Palmer's closed for lack of orders, the whole town suffered.

This spring there was growing agitation along the riverside for a nine-hour day among the steelmen and mechanics. Rose had heard her father say so. There would be hardship the length of the River Tyne if it came to a strike. Talk of strike action made Da angry, for he held no truck with union agitators. As a youth he had been one of many brought over from Ireland by Lord Londonderry as a strike-breaker in the pits, and had done well enough finally to rent a piece of land and buy his first cow. When the talk on street corners was of squaring up to the bosses, it was best to humour McConnell or keep out of his way. Both Rose and her mother understood this, but Rose's younger sisters seemed oblivious to the tension gathering about them like storm clouds. Lizzie and Maggie played and fought like young kittens and left the worrying to their fourteen-year-old sister.

Her mother threw Rose a despairing look.

âI'll go,' the tall girl offered, already reaching for her shawl. It was faded, fringed and old-fashioned, but had belonged to her dear grandmother and when Rose wrapped it about her and pulled it over her dark hair, she felt the dead woman's strength and was comforted. âNever fear the dark,' Granny had always told her. âGod sees everything, even in the pitch-black of night.' And soon what daylight there was on such a gloomy day would be gone, Rose thought anxiously. The quicker she got the delivery over, the better. She had no desire to be stumbling around Jarrow's dirty unlit lanes or be caught anywhere near the Slake. Rose shivered to think of the putrid, stinking inlet, known locally as the âSlacks'. It had to be crossed to reach the old pit cottages where the McMullens lived.

âThanks, hinny,' her mother said, as Rose began to load up a basket. âAnd take a few eggs to sell round the doors while you're out.'

Rose's heart sank, but she did not waste time protesting. The steelworkers and dockers were their main customers and the McConnells would have to put by all the pennies they could get now, if they weren't to suffer later. Rose felt impatient with her sisters for not realising this, but as she went, felt a stab of envy for their carefree laughter and ability to live for the moment.

Rose went into the henhouse at the back of the cottage and collected half a dozen eggs, which she put in a basket over her arm. The heavy vegetables she balanced in an old fishing creel on her head. She was used to going about the town like this, selling their produce from door to door. She would chivvy her sisters into helping her scrub the vegetables and arrange them nicely, so that people were more tempted to buy. Customers seemed to like her quiet, polite way of speaking and her shy smile. Rose would sometimes allow her regulars credit, keeping a tally in her head of who owed what.

The poorer they were, the better the customer, Rose had discovered, for they were prisoners in overcrowded tenements, burdened down with children and often denied credit at the shops. Rose brought a cheerful greeting and a winning smile into their drab day, knowing they would find the pennies for her by the end of the week.

The McMullens were another matter. Rose felt mounting nervousness as she skirted the centre of Jarrow and made her way downhill towards the Don, an oily slick of a stream that emptied into Jarrow Slake. She doubted she would receive any payment from the McMullens, despite several of the sons now old enough to be working as labourers in the docks. Old McMullen, or âthe Fathar', as they all called him with fear in their voices, was a burly brute of a man who worked in the ironworks carrying the heavy âpigs' of iron from their moulds to waiting wagons. Strong men were needed for such a back-breaking job and McMullen had come over from Ireland to do just that. He hailed from the same part of Ireland as Rose's father and so McConnell insisted on helping them out where he could.

âWe've both known the Famine,' McConnell had told his daughters, âand I'll not see our people starve when we've got food growing beneath our feet. We're from the same village.'

Rose's mother had muttered, âAye, and that McMullen seems to be doing his best to father his own village! With all them lads, isn't it about time they paid for some of our food?'

But McConnell had given her a sour look. âThey'll pay when they can. At least he's got plenty to carry on his name.'

Rose felt troubled when she thought of her father's barbed remarks about his lack of sons. Her mother got all the blame. Rose often lay awake at night listening to their hissed arguments.

âI'm past giving you bairns,' her mother had said wearily.

âNo you're not,' her father had protested. âIt's your duty. Hasn't Father Boyle told you often enough?'

âI've done my duty!' Her mother had grown agitated. âIt's not my fault if scarlet fever carried off my two bonny lads.'

âMaybe if you'd kept this place cleaner...' Rose's father had grumbled.

A sob had caught in her mother's throat. âDon't you dare blame me! Blame yourself for bringing me to live in this terrible place. We should have stayed in Gateshead like I wanted - or gone back to Lamesley.'

âAnd have you be at the beck and call of that old witch your mother?'

Rose had buried her head under the blanket in distress at hearing her dear grandmother called a witch. She'd tried to block out their tired bickering, but she'd heard her mother protest that daughters was all he was going to get. âBearing another bairn now would kill me. Then who would run this place for you or bring up your lasses to be hard-working and respectable? Ask your precious priest that.'

âI ought to take me belt to you for your cheek!' Da had growled.

âAye, just like McMullen?' Ma had scoffed. âI don't care how many sons he has, there's nowt manly about beating his missus. If you want me strong enough to lift tatties from the ground you'll leave us alone and let me get some sleep.'

Rose hurried on as fast as her load would allow, her heart thumping at the memory of her parents' argument. What was it that her da had wanted her ma to do? And why was her mother's voice filled with such disgust at the idea? What went on in the marriage bed beyond the thin partition, Rose was not really sure, and was too frightened to ask. Occasionally there would be creaking and restless movement, but, more often, whispered protests or exhausted snoring from both parents.

As she neared the foul-smelling Don, Rose's mind went back to that blustery spring day in Lamesley when she had seen Lord Ravensworth's daughter married to an army officer. She had been so clean and beautiful in her white dress, her face suffused with happiness, tinged pink with excitement. Rose had thought of her for years as a guardian angel, conjuring her up in her mind when she was frightened or unhappy. When I marry, Rose promised herself, I want to look like her. She might never be able to marry a handsome officer in a scarlet coat, but she would work hard to afford a pretty dress and choose a man who would bring her happiness and security.

Putting down her burden, she rested a moment in the blackened shadow of the ancient ruined monastery, St Paul's. Once this had been the home of St Bede in a golden age of Christianity, her Sunday School teacher had told her. Even at the time when Queen Victoria had come to the throne, in Granny's lifetime, it had still been a place of fields, small boat builders and sail-cloth makers. Now it was hard to imagine it had ever been anything else but this hellish landscape.

The sulphurous smell from the chemical works was overpowering, and the sky was an oppressive grey haze from the belching chimneys of chemical factories, paper-mill, coke ovens and steel mills. The leaden horizon was peppered with steaming salt pans, jutting coal staithes and a forest of rigging and cranes on the river's edge. Even from this distance, the clatter from the docks and the thump of giant hammers in the rolling mills carried loudly over the blackened rows of houses.

Rose felt the metallic taste on her tongue that soured her mouth whenever she drew near to the ironworks. Below her the Don oozed its way into the muddy Slake where the ebbing tide had left its flotsam of seasoned timbers stranded like a shattered vessel after a shipwreck. In the gloom she saw children playing on the precarious network of planks, jumping from one to another and daring each other to follow. She would never allow her future children to play in such a dangerous place, she determined. When she married the kindly man of her imagination, she would live well away from this sinister part of the river, with its uneasy ghosts.

She knew from her grandmother that this part of the riverside was haunted. Apart from those who had slipped and drowned in the fetid waters of the Slake, it had been the site of the last public gibbeting. Granny had told her about the miner Jobling who had been hanged for his part in the murder of a magistrate during a terrible strike. They had brought his body from Durham Gaol, smeared it in black pitch and trussed it up in an iron gibbet for all to see.

âStuck it right there in the muddy waters where the tide comes in,' Granny had told her, âto be a lesson to the pitmen and their families that they can't take the law into their own hands. They say Jobling's widow could see him swingin' there, from her very doorstep. Aye, and people came from all over to see the terrible sight. Soldiers guarded it night and day,' Granny had continued in an eerie voice, âbut there was something devilish about that pitman. One day it disappeared - the whole lot - body, gibbet an' all! Nobody could have cut it down - it was solid iron - and anyone who tried was threatened with seven years' transportation! Some say it were his pitmen friends who risked their lives to do it - buried him out at sea. But I think it was witchcraft. On windy nights you can still hear Jobling's ghost moanin', and see him swingin' there when there's a full moon. That's what I've heard. So you stay away from that place!' Granny had warned. âHe'll get you like the bogeyman if you stray down too close to the river.'

Rose felt familiar fear weaken her knees. Many nights she had lain awake thinking she could hear the groaning of Jobling's unhappy ghost carried to her on the wind. âWill he be in Hell or Purgatory?' she had asked her mother, deeply troubled that the pitman had not had a Christian burial.

âThat's not for us to judge,' her mother had answered shortly.

âBut he was a murderer, Ma, wasn't he? And he never got properly buried. That's why his ghost still haunts the Slacks when there's a full moon, isn't it? Granny says witches must've carried off his body.'

âStop talking daft,' her mother had said impatiently. âAnd don't go repeating such tales to the priest, or he'll think we're a family of heathens.'

Rose glanced up at the sky now, but there was no way of knowing if a full moon was on the rise or not. She took a deep breath in the acrid air and told herself not to be so fanciful. It was just one of Granny's stories that she liked to tell over a winter fire, and Ma had told her not to believe half of what Granny had said. Besides, the moon was her friend. Why should she be frightened on such a night?

All the same, Rose decided to go the long way round and doubled back up the hill, skirting the banks of the Don until she could cross it higher up near the turnpike road that led all the way from South Shields to Newcastle.

By the time she reached the long rows of pit cottages, she could hardly see to pick her way over the stagnant pools that collected in the rutted, uneven lanes. Rose pulled her shawl over her nose to try to deaden the stench of rotting household slops and sewage that leaked out of the earth closets and oozed into the yards and through the walls of the ancient cottages. They had been abandoned long ago by mining families when the Alfred Pit had closed, and no landlords had bothered to spend any money on these hovels that now housed Jarrow's poorest. Whole streets were taken over by Irish labourers, their wives hooded in thick shawls that they pinned under their chins.

Several of these hardy women were now lined up patiently at the standpipe at the top of the street, waiting to fill kettles and pails of water. Their quick chatter and sharp calls to their scampering, barefoot children rang through the murky twilight.

âIs that you, Rose McConnell?' one of them shouted.

âAye, missus,' Rose called back. âI'm going to Mrs McMullen's. But I've a few eggs spare. Fresh as they come. They'll be a treat for your man's tea.'