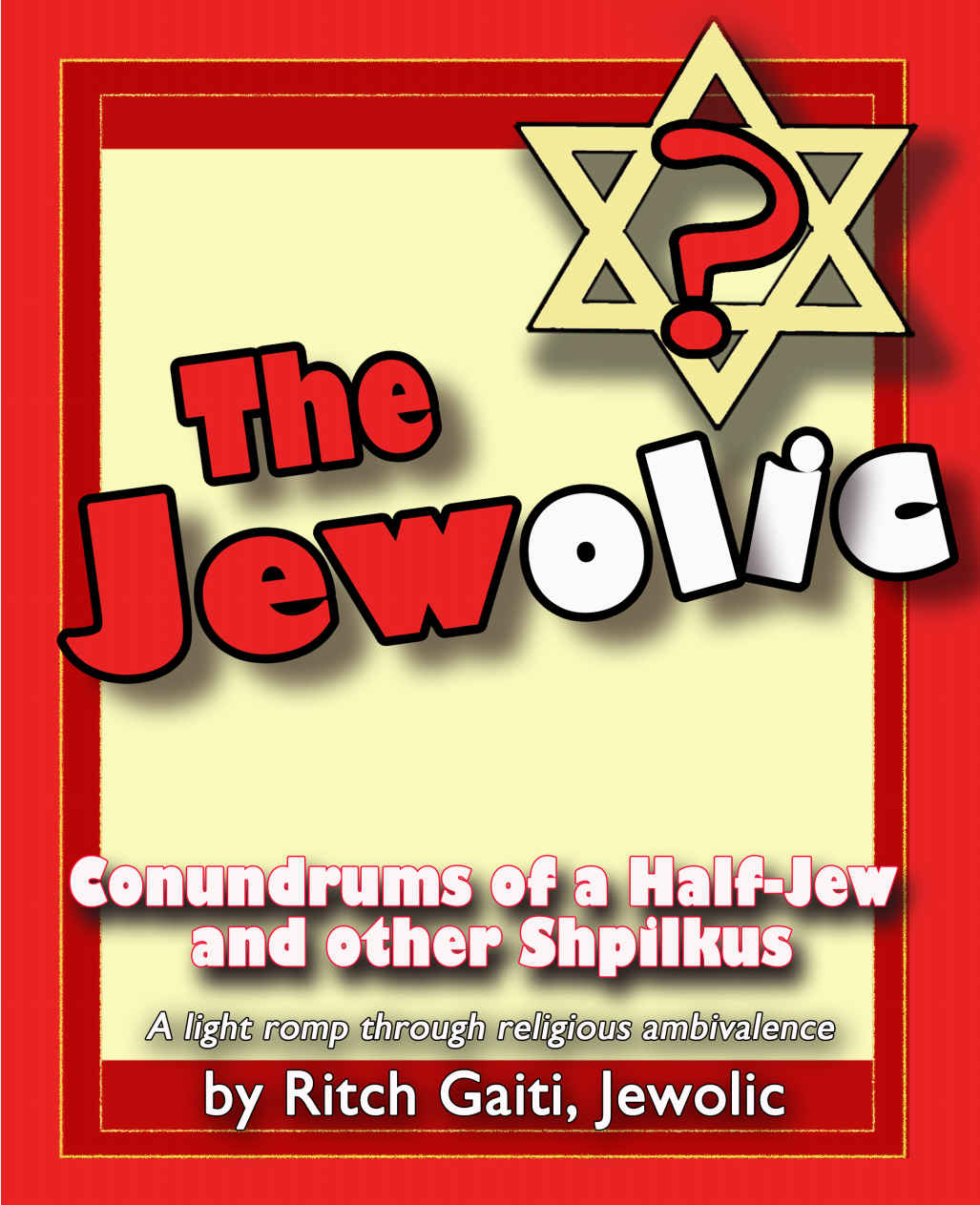

The Jewolic

Authors: Ritch Gaiti

Conundrums of a Half-Jew

And other Shpilkus

A light romp through religious ambivalence

By Ritch Gaiti, Jewolic

Published by:

www.SedonaEditions.com

[email protected]

ISBN

978-1-4929339-6-0

©

2013 by Ritch Gaiti

Dedicated to

Grandma and Nonna

The sweetest ladies on the planet

Introduction

Polish/

Jewish mom; Italian/Catholic dad. I was a religious mutt — a matzo brie pizza; a blintz marinara; a bagel and lox trapped inside a spaghetti and meatballs body. I needed an identity.

I could have become

:

a)

A Jew, invoking the very popular, and all-inclusive, ‘

if your mother is a Jew’

rule;

b)

A Catholic, ignoring the above-mentioned rule; or,

c)

A half Jew/half Cath, Jewolic, straddling both religions, favoring the one that was most advantageous at the time.

That was my conundrum.

This is my story.

Note: The Jewolic is totally true except for when Grandma tossed her uppers into the meatloaf; it was actually the pot roast. And a couple of other minor instances.

1

Enter the Jewolic

“Is there a God?” I queried my kosherest of grandmothers for enlightenment but mostly to break her concentration during our daily card game.

“Don’t be silly. Where do you think Double Solitaire came from? It was just here?” Her focus remained on the game as her hands flew across the cards at uncanny speed.

“Maybe the guy who invented regular Solitaire invented it.”

“Ha. Who invented him? Don’t be a schmuck. Of course there’s God.” She seemed very convinced as she took a deep drag on her daily Kent without bothering to remove the cigarette from her mouth. She blew a lungful of smoke in my face as she quickly

laid off all of her cards, the last one with a table-slamming: “I win.”

I had always suspected her of cheating but, since I could not see her hands through the miasma, I had not been able to catch her in the act.

“Are you sure?” I snorted in a pound of mucous. It was hard to believe that so much smoke could come out of a five foot gray haired old lady.

“Of course, I’m sure. You have cards; I have no cards. I win. It’s the rules. I am the winner. No two ways about it.” She counted my cards and reached into her purse, extracting a pencil stub and envelope from which she withdrew several large folded papers which she very delicately unfolded and hand-ironed. “You owe me thirty six cents.”

“Put it on my account.” I sleeved my nose.

“I did.” She wrote carefully, folded the papers neatly and returned them to their nest.

“You did? I have an account? Since when do I have an account?”

“It’s your inheritance account and I’ve had it since you were no bigger than a pupick. Each year, on the celebration of your birthday, I add one dollar additional, regardless. Every time you lose in cards or do something else that perturbs me, I deduct. Today, I have subtracted thirty-six cents from your bequest. And it grows ever smaller. Pretty soon it won’t pay for you to show up at the reading, that is, if you were planning on coming in the first place.” She snapped the clasp of her purse shut signaling the end of the conversation. She smiled

as her uppers slid down a notch.

“I’ll be there, if I’m not too busy watching TV or playing stickball or something. Bequest? What bequest? You live here with us. All you have is an iron and a housedress. You can’t leave me anything if you don’t have anything.” I loved to jab her about living with us

— mom, dad, and my sibling units, one male and one female; it was the only quality defense that I had.

“Mox nix. It matters not. Whatever I do or do not have, you will get thirty six cents less of it.” She leaned back and took a victorious drag on the Kent and sent a stream across my bow.

That’s when I decided that I could never have a conversation about the existence of God with Gram. There is no convincing, debating, swaying, reasoning, arguing, facts, statistics, analytics, reckoning, common sense or logic. I figured that you either believed in God or you didn’t.

Our positions were clearly defined: she did

, and I was one hundred percent unsure. In a way, I admired her conviction, which was far less stressful and time consuming than my oscillation. While she ironed and watched

As the World Turns

, I would lay on my bed staring straight up in His or Her direction debating His or Her existence. Gram would spend a carefree afternoon finishing the ironing; I, on the other hand, came away wondering why anyone would put wallpaper on the ceiling.

2

The ‘mother of the Jew’ rule

I attributed my condition and current state of mind to my quasi half breed upbringing: the offspring of a Jewish mother, begotten by a pair of good old fashioned European Jew begetters, and an Italian Catholic father. Not feeling the pressure to make a commitment either way, I actually straddled religions for most of my youth. I was a Jew Catholic, or Cath Jew, or half and half, or half Cath, or half Jew, or Jewolic, depending upon whom I was trying to impress or what I was attempting to avoid.

I dispelled the very popular ‘

if your mother is Jewish, then you are too’

adage which only worked if one were Jewish and subscribed to that belief in the first place, rendering the axiom moot.

“If you were Catholic,”

I inquired of Gram during one of our card games mostly as a red herring, which was not the usual kind of herring that occupied our dinette set. “Just saying, not that you are or ever could be, but if you were, hypothetically speaking, say Catholic, would I be Catholic also?”

“No.” Gram said directly without diverting any concentration from the game. “You would be a Jew because I am not Catholic, end of story.”

“But who made the rule?”

“A rule is a rule. It doesn’t matter who made what.

Who made the dollar one hundred cents? Who made the gefilte fish? Mox nix. It’s a rule; you follow it. That’s why they call it a rule, end of story.”

“But why isn’t the rule:

if your mother was Catholic, you are too

?” I always called up the

mother of the Jew rule

when I had an urgent need to irk. “Or, if your father was Catholic, you are too? Or, if your mother was a Jew and your father a Catholic, then you are a half and half? Those could be the rules.”

“Because you are a Jew,”

she said, a cigarette dangled from her lips and smoke meandered up through her glasses.

“How can you be so sure?”

“Because, you are a schmuck and only Jews can be schmucks.” She had embroidered the very same saying onto a pillow, which she threatened to give to me for my birthday. She opened the clasp on her purse and snapped it shut, signaling the official end of the conversation.

Gram believed it

, so it was true and I was Jewish by default. It really didn’t matter much. I mean, it was nice to be something; she chose to be Jewish; well, she really didn’t choose it, she just was. I suspect that she was fortunate to inherit a religion, leaving life’s choices and decision making to less acute issues such as the appropriate laundry detergent and mastering the art of cooking without taste. I, with my birthright a tad muddier, was left the legacy of having to define my own path, determine my own fate and choose my own belief system. I had one foot in the Jew camp, the other on the fence. I just wasn’t ready to commit but if Gram wanted me to be Jewish, then for her I was Jewish, mox nix.

Most of my friends were Jewish

. Morty Milberg, my public school jff, even wore a mezuzah, which I considered a pretty cool neck ornament that I would have considered wearing if it had no significance or I could ascribe my own meaning which would most likely be something to do with Indians or Kryptonite. But it did and I didn’t, so I wore a chain sans ornament, long before it was popular to do so.

The only real difference between my Jew friends and my not-Jew friends was that the not-Jews were the ones playing stickball after school while the Jews went to Hebrew School, another inconvenience of

religion. No one ever heard of a Jewish all-star stickball player, except for Morty, who excelled at both sports and school, clearly an anomaly. It was pretty clear to me that Morty was on the path of great conflict when he would have to decide between becoming a rabbi or pitching for the Dodgers, a conflict conquered only once by Sandy Koufax, the first Jewish southpaw to throw a no-hitter. I chose to avoid such clash through my religious vacillation and my stickball mediocrity.

The very thought of going to school after I had just finished a hard day of tolerating school was pretty repulsive. I didn’t think it was a very good selling point for a religion that was always looking for new recruits. If I were to start a religion, I would offer two weeks off fro

m any school as a signing mitzvah (Author’s note: Mitzvah is an act of human kindness: check Wikipedia as I did). I would then reward my followers with a four-month summer respite, which I would call B’nai Beach, and a winter holiday, in celebration of the crossing into Flatbush, which took place most likely before 1950, and a day of remembrance for the day the Dodgers departed Ebbets Field in search of the Golden Fleece. Of course, Fridays would be extra religious half days to observe Hebrew National Football or Baseball depending upon the season.