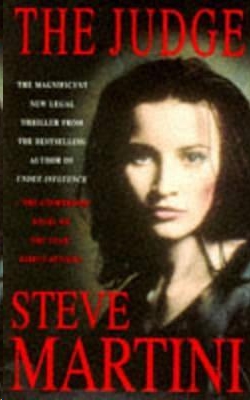

The Judge

THE JUDGE

Paul Madriani Book 04

Steve Martini

Synopsis:

Judge Armando Acosta has been summarily dismissed from the bench after being arrested on what he maintains is a trumped-up charge of soliciting a prostitute. When the key witness in the case against Acosta is found murdered and all the evidence points to Acosta as the killer, the former judge suddenly finds himself in desperate need of a tough, savvy lawyer to handle his case. An ironic set of circumstances eventually leads him to his longtime enemy Paul Madriani, who must combat police corruption, slurs against his own reputation, physical attacks, uncooperative witnesses, and a flamboyant, politically ambitious prosecutor who's as dangerous as a cobra. In a series of suspenseful courtroom scenes, Madriani mounts a tenuous but ultimately brilliant defense, racing against time to find the evidence he needs--and is certain exists--to prove his client's innocence. A keep-'em-guessing page-turner that will keep readers riveted.

She is like a ROSE: TALL AND SLENDER, WITH COMPLEXION of a dusky hue, eyes and teeth that flash, and a manner that at times produces its own

barbed thorns.

Lenore Goya has been a friend since my brief stint three years ago as special prosecutor in Davenport County. Except for a couple of brief encounters in the courthouse, I have not seen her since shortly after Nikki's funeral. On several occasions I have considered calling her, but each time I suppressed the impulse. I have never aspired to the image of the widower on the make, and have silently subdued all desires.

Yet when she called I knew she could sense the yearning in my voice. Tonight I meet her at Angelo's, out on the river. It is brisk. A light breeze sends flutters through the Japanese lanterns overhead. The tables are set on the wharf at the water's edge. Pleasure boats bob at their slips in the marina beyond. I've dressed in my casual finery, a look that required two hours of preparation. It sounded more like business than pleasure when she called. Still, I am hopeful.

When I see her, she is across the way, on the terrace, a level above me. Lenore is dressed for the occasion, wearing a pleated floral skirt, tea-length, and a bright pastel sweater with a rolled collar. Lenore as the shades of spring.

She sees me and waves. I am casual, breezy in my return, just two friends meeting, I tell myself, though in my chest my heart is thumping.

This evening she is lithe and light, both in body and spirit. Lenore's fine features are like chiseled stone--high cheekbones and a nose that, like everything else about her, is sharp and straight.

She wends her way through the mostly empty tables. The crowd has opted for the indoors, a hedge against the chill of the evening air. It is not quite summer in Capital City.

She turns the few heads as she approaches. Lenore is one of those striking women who become a focal point in any room. Hispanic by heritage, she has the look of the unspoiled native, a visual appeal that hovers at the edge of exotic, Eve in Eden before sin.

"What a wonderful place," she says. A peck on my cheek, the squeeze other hand on my arm, and I am a rung out.

"It's been such a long time," she says.

bouncing off the ropes like rum-dumb boxers. We have as yet not encountered each other in court, and I wonder how this will affect our friendship when we do. I may never know.

There is word of stormy waters in her office. Duane Nelson, who hired Lenore, has left to take a spot on the bench. He has been replaced by a new, more acerbic and insecure appointee. Coleman Kline is a political handmaiden of the county supervisors. He is busy putting his own mark on the office--rumblings of a purge.

According to Lenore, each day when she goes to her office she looks for blood on the doorpost and wonders whether the Angel of Death will pass over--in this case, a woman named Wendy, who delivers the pink slips to those who are canned. "So many people have been fired," Lenore says.

Without civil service protection, and holding a prominent position in the office, Lenore is a target of opportunity. There are a dozen political lackeys who hauled water in the last election now vying for her job, trying to push her out the door.

The waiter comes and we order cocktails and an appetizer. He leaves and I study her for a moment in silence as she watches a motor yacht sail upriver, its green running light shimmering on the water.

When she looks back she catches me. "A penny for your thoughts," she says.

Somehow I suspect it is not this--the travails in her office--that is the reason for our meeting.

I'd like to believe that you called because of my charm," I say.

"But you're thinking there's some ulterior motive?" She finishes my thought.

I smile.

"You're very charming." Her eyes sparkle as she says this, like the shimmering dark waters beyond. There are dimples in each cheek.

"But?" I say.

"But I need your help," she says. "I have a friend," she tells me. "a police officer who is in some difficulty..." You HAVE TWO CHOICES," HE TELLS ME. "your MAN testifies, or else."

"Or else what? Thumbscrews?" I say.

He gives me a look as if to say, "If you like." Armando Acosta would have excelled in another age: scenes of some dimly lit stone cavern with iron shackles pinioned to the walls come to mind. Visions of flickering torches, the odor of lard thick in the air, as black-hooded men, hairy and barrel chested, scurry about with implements of pain, employed at his command. The "Coconut" is a man with bad timing. He missed his calling with the passing of the Spanish Inquisition.

We are seated in his chambers behind Department 15, sniffing the dead air of summer. There is an odor peculiar to this place, like the inside of a high school gym locker infested by a soiled jockstrap. Seven million dollars for a new addition to the courthouse, and the county now lacks the money to change the filters on the air conditioning a marble monument to the idiocy of government.

Acosta settles back into the tufted leather cushion of his chair, the manicured finger of one hand grazing his upper lip as if he were in deep contemplation.

"I will hold him in contempt," he says. "And I will not segregate him.

No special accommodations." This idea seems to please Acosta immensely, confirmation of the fact that the judiciary is still the one place in our system where authority can be abused with virtual impunity, especially here in the privacy of his chambers.

"The jail is overcrowded." He says it as though this condition offered opportunity.

"And you know the risks to a cop in the general lockup. Some of those people in there are animals. What they might do to him ..." He would draw me a picture, his version of "hangman," but with the stick figure on its hands and knees, its Y-shaped rump in the air.

Acosta's talking about my client. Tony Arguillo is in his mid-thirties and good looking, a neophyte cop with the city P.D., only four years on the force. He has now been subpoenaed by the grand jury. He is related to Lenore, some distant family connection, the cousin of a cousin, something like that. But they are closer, it seems, than blood would indicate.

Tony and Lenore grew up together on the tough streets of L.A. It seems he was the muscle, she was the brains.

Arguillo is now the ball in a game of power Ping-Pong between the Police

Association and the city fathers, a brewing labor dispute turned ugly.

The last volley, a backhand shot by the Coconut on behalf of the mayor and the city council, has sent my client across the net into the union's side of the table, ass-end first.

The city has leveled charges of police corruption, something they would no doubt swiftly drop if the union found a quick cure for the blue flu, a rash of cops calling in sick. Acosta for his part is currying favor with the power structure, other politicians who can, if he does the right thing, give him cover in an election--or if he loses, a cushy appointment to some city job that doesn't need doing.

The Coconut is out to break the police union. They have endorsed his opponent in the upcoming election and are busy tunneling vast sums of money to their candidate of choice.

It is true what they say about most judges. The principal qualification for the office is that they are lawyers who know the governor. And now this one, the man I hate, has my client by the unmentionables.

Unfortunately for Tony Arguillo, what started out as a few loose and unfounded charges has suddenly grown hair. There is now budding evidence that some union dues and pension funds were skimmed by a few of the union higher-ups. Things are quickly escalating to the point of public disclosures from which prosecutors can no longer divert their eyes.

We banter back and forth about the substance of these charges. I call them "gossip, unfounded conjecture," and pray that the D.A. has not completed an audit of the funds. Acosta for his part tries a little moral indignation. This is like spinning gold from straw, given the man's limited virtue.

"Can you believe?" he says. "Officers are now handing out flyers at the airport, telling tourists that this city is unsafe. Can you believe the arrogance?" he says. This is whispered, hissed through clenched teeth, low enough so that Acosta's bailiff, who is outside chewing on sunflower seeds and spitting the shells on the carpeted floor, cannot hear it.

"Like there's some direct correlation," he says. "As if the guy who robbed you last week wouldn't have done it if the cops had gotten their eight percent pay hike in Friday's envelope. They make it sound like they're selling protection," he says. "Unprofessional," he calls it.

"Fucking extortion," he says, as if profanities and veiled threats of physical force against my client by a judicial officer were acts of high moral tone.

I tell him this.

"I didn't threaten anyone. And I take offense..."

"I'll tell my client that when you put him in the cell with Brutus." "He's putting himself in that cell." This is deteriorating. I try a little reason.

"My guy was just the bean counter," I tell him. "He kept the union books."

"Cooked them is more like it," says Acosta. "From what I hear, the union fund is about a half million light." I give him a look, like news to me. "Maybe you should ask the union officers. Tony wasn't even the treasurer. He just did the books on the side, a favor for some friends.

"

"No doubt," he says. "He was probably the only one in that crowd who could count beyond double digits without taking off his shoes." Acosta does not have a high opinion of cops. To him, the competent ones are people to be shot at during times of danger; the more inept can spit-polish his black, pointy cowboy boots in moments of tedium. I have actually seen his bailiff doing this chore.

My client has sworn to me on successive occasions that he has taken b shh no money. Still I suspect Tony knows where substantial quantities of it are buried, like bleached bones, and who among his cabal of junkyard dogs did the digging. It is this, evidence of some criminal conspiracy and financial fraud within the union, that Acosta wants--something he can trade with the city bosses, a political commodity like pork bellies. It would break the union's back, send the boys in blue, tails between their legs, scurrying back to work. In short, a criminal indictment would bust what is now a budding strike. "You issue an order for contempt," I tell him, "and we'll get a stay. Take it to the appellate court."

"In two or three days maybe." Acosta's face says it all: In the meantime your client gets a whole new insight into the human sex drive.

This is an outrage and I tell him so, a potential death sentence to an officer who is only on the fringe in this thing, not one of the movers and shakers in the association.

There is something dark and subterranean in Acosta's smile as he stares at me from the other side of the desk, its surface littered with papers and assorted objects the culturally deprived might call art. There is a metal work of Don Quixote tilting at a tin windmill, a gift from some gullible civic group that mistook the judge's avarice and political ambitions for a noble quest. The only thing the Coconut has in common with this metal rendition of fiction's great Don is a hard ass.

"Do we have an understanding?" he says. Acosta is in my face. "Let me see if I got this right: You want my client to give up his rights--maybe incriminate himself. If I refuse, you will stick him in a cell with some animal and let the law of nature take its course." He gives me an expression, the loose translation of which confirms my description of the options available.

"Maybe we should call in the reporter and put it on the record," I tell him.

His thin lips curl, a dark grin, as if to say, "Fat chance."

"Your man is going to talk or do time, maybe both," he says. "But he is going to talk. You should prepare him for that."

"You make it sound personal," I tell him. "No. No. It is not personal."

"Then political," I say.

"Ah. There you have me." With Acosta there is no embarrassment in admitting this. "There is always a price when you back the wrong horse in a race." He searches for a moment, then says: "What's his name Johnston?" He is at least honest about this. It is business. He can't even remember the man's name who is running against him.

"It is..." He thinks for a moment, finds the right word. "... a matter of survival," he says. "I've been on this bench for twenty years.

Treated them decently. Never abused a man in uniform on the stand. And they do this," he says.