The Judgment of Paris (21 page)

When, in the late summer of 1863, Manet was ready to paint the work in oil, he chose a canvas six feet wide by some four feet high—smaller than the showstopping grandeur of

Le Déjeuner sur I'herbe

but still large enough to command attention in the Salon. Difficulties soon arose, chief among them Victorine's face, which Manet was forced to scrape down and repaint several times.

13

He also experimented with Laure's figure, providing her with, on second thought, more generous curves, repainting her dress at least once and omitting the jeweled necklace. Finally, at the end of his labors he added, almost as an afterthought, a touch absent from his earlier sketches: in place of the lapdog curled at the feet of Titian's Venus he substituted a black cat with an arched back and erect tail. Like the frog in

Le Déjeuner sur I'herbe,

the animal might have been intended as a visual pun, for

les chattes

was a slang term for both female genitalia and prostitutes.

14

Manet scarcely needed to add the black cat in order to suggest exactly what was happening in his scene. Victorine was clearly cast in the role of a prostitute receiving a gift of flowers from an admiring customer. She was not, however, a prostitute like the lower-class "unruly woman" hinted at in

Le Déjeuner sur I'herbe,

but rather what was known legally as

a fille de maison.

A prostitute of somewhat higher standing,

the file de maison

worked in a brothel, entertained a better class of client, and often adopted for herself an exotic name such as Arthémise, Octavie or Olympe. Manet even called his painting

Olympe

("Olympia"), thereby leaving little doubt about how the reclining young woman earned her living. The name may have been a direct allusion to the courtesan Olympe in Alexander Dumas

fils's

novel

La Dame aux Camélias,

first published in 1848 and turned into a popular stage play four years later. Another courtesan with the alias Olympe had appeared in 1855 in Émile Augier's

Le Mariage d'Olympe.

15

Depicting a courtesan in so unmistakable a fashion was a bold and provocative move on Manet's part considering how Alexandre Cabanel, only a few months earlier, had taken such a battering from the critics who accused his Venus of looking like a prostitute from the Rue Bréda. Prostitution may have been legal in the streets and brothels of Paris, but it was still very far from being acceptable on the walls of the Salon. And while Cabanel had at least executed his work with an unimpeachable technique, Manet applied his paint to the canvas with the same supposed lack of control and finish that had put one critic in mind of a floor mop. As in

Le Déjeuner sur I'herbe,

he painted Victoria's face, torso and limbs with none of the sculptural three-dimensionality and careful modulations of color to which Salon-goers were accustomed. Instead, using sharp contrasts of color, he created her body through a series of flat planes, producing a two-dimensional image that almost served to make the canvas seem a parody of Titian's curvilinear

Venus of Urhino.

Part of Manet's inspiration for this technique probably came from photography. Painters had almost always required a muted light in which to work. The ideal studio was lit by a large north-facing window that diffused the sunlight and allowed the painter to see—and to capture in pigment—the softest and subtlest tones. Photographers, however, worked under quite different conditions. Anyone hoping to produce a photograph in the middle of the nineteenth century needed bright illumination since the first chemical emulsions were stubbornly insensitive to light. In the days before the invention of flash powder (a mixture of potassium chloride and powdered magnesium first successfully employed in the 1880s), photographers were forced to turn on their sitters various forms of artificial light. Most of their pyrotechnic devices, such as "limelight," a sheet of lime heated with a hydrogen-oxygen torch, had provided a harsh, brilliant illumination that resulted in photographs with pronounced tonal contrasts.

*

Photographs therefore displayed far fewer varieties of tone than was found on canvases. If Victorine had indeed been photographed by Nadar (who sometimes used battery-powered arc lamps to cast light on his subjects), the result would not have been dissimilar to the stark image Manet produced on his canvas, whose lack of detail, moreover, resembled the hazy images produced by photographers as a result of the long exposures required by paper-negative prints.

16

Manet's peculiar rendering of Victorine reclining on her pillows probably had another source as well. Besides photography, his work owed a debt to Japanese woodcuts. In the years since the 1854 Treaty of Kanagawa ended Japan's two centuries of isolation and opened her ports to foreign trade, Oriental woodblock prints and other handcrafted artifacts such as painted fans and folding screens had begun making their way to Europe. Manet was not as devout a collector of such bric-a-brac as Whistler, who had been stockpiling Japanese artifacts since the early 1860s. Even so, he was a regular visitor at La Jonque Chinoise, a purveyor of Japanese art in the Rue de Rivoli, and one of his proudest possessions was a print of a sumo wrestler done by Kuniaki II. The disregard for linear perspective found in the woodblock prints of Japanese artists such as Hokusai, as well as their lack of subtle shadings of color, clearly appealed to Manet, offering him a precedent for his own stylized representations.

17

Work on this canvas was probably more or less complete by the first week of October in 1863. By dint of both its style and its subject,

Olympia

almost seemed calculated to raise the same wrathful response as

Le Déjeuner sur I'herbe.

Still, Manet had other matters to worry about by the time he finished his provocative new painting. At the age of thirty-one, he was about to get married.

Besides being a photographer, Nadar was also, even more wondrously, an aeronaut. In 1863 he founded the Société generate d'Aerostation et d'Autolocomotion Aerienne, started up a newspaper called

L 'Aeronaute,

and constructed the world's largest hot-air balloon. The aeronautical possibilities of hydrogen balloons had captured the public imagination. A few months earlier, an unknown thirty-five-year-old named Jules Verne, a former law student, had published his first novel,

Five Weeks in a Balloon,

in which he imagined the voyage across Africa of three Englishmen in a giant hot-air balloon named the

Victoria.

The fictional

Victoria

had been inflated with 90,000 cubic feet of hydrogen, but Nadar's real-life balloon managed to outstrip even Verne's exuberant imagination. Christened

Le Ge'ant,

it was borne aloft by 200,000 cubic feet of hydrogen, stood 180 feet tall, and used almost twelve miles of silk that two hundred women had required an entire month to sew together. Included in the wicker-work gondola, which was the size of a small cottage, were a photographic laboratory, a refreshment room, a lavatory and, for the amusement of the passengers, a billiard table.

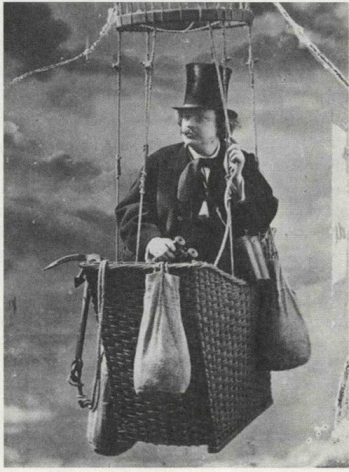

Studio photograph of Nadar in a balloon

On October 4, a Sunday, more than 500,000 people—almost a third of the entire population of Paris—crowded onto the Champ de Mars and surrounding streets, and even onto nearby housetops, to witness the maiden voyage of this magnificent vessel. A military band played for two hours as the gondola was towed into place by four white horses and the balloon, which one journalist claimed looked like "an immense unripe orange,"

18

was inflated with gas. Twelve passengers besides Nadar then climbed aboard, including the art critic Paul de Saint-Victor.

"Lâchez tout.!"

shouted "Captain" Nadar at five o'clock in the afternoon, and the gigantic balloon rose skyward, sailing northeast across a silent and awestuck Paris, passing over the Invalides and the Louvre before finally disappearing from view. But unlike the

Victoria,

which sailed all the way across Africa,

Le Giant

stayed airborne for only a couple of hours before a technical malfunction in a valve line forced Nadar to make a premature descent into a marsh near Meaux, some twenty-five miles away. By the time he and his dozen passengers were rescued, the enterprising aeronaut was already making plans for a second voyage.

Two days after Nadar's spectacle, Manet and his mistress Suzanne Leenhoff made their own, less spectacular, departure from Paris. Manet's mother and two brothers had witnessed a marriage contract between him and Suzanne, who was then age thirty-three. According to the terms of the contract, Manet would receive the 10,000-franc advance on his inheritance from the proceeds of selling the fifteen acres of family land in Gennevilliers. This sum would allow him officially to set up home with Suzanne and Léon. The contract stipulated, curiously, that these 10,000 francs would return to Manet's mother should he predecease her with no children of his own.

19

This rather mean-spirited provision, no doubt added at the insistence of Eugénie Manet, indicated that Léon, who would suffer under its application, was probably not Manet's flesh and blood. It also indicated how Eugénie—known to her children as "Manetmaman"—nourished a robust dislike for her prospective daughter-in-law, whose misfortune in giving birth out of wedlock she once referred to as a "crime" in need of "punishment."

20

Manet's joyful anticipation of his forthcoming marriage must have been tempered by the knowledge that, as long as Eugénie was alive, domestic tranquillity could not be guaranteed.

Family resentments and rivalries were set aside, temporarily at least, as the Manet family assembled for lunch in the Batignolles on October 6 to celebrate the impending nuptials. Present for the feast was Suzanne's brother Ferdinand—one of Manet's models for

Le Déjeuner sur I'herbe

—and her younger sister Martina, who had moved to Paris like her siblings, gallicized her name to Marthe, married the painter Jules Vibert, and given birth to two children. The forty-eight-year-old Vibert, a native of Lyon, was a considerably more successful painter than his soon-to-be brother-in-law. A former student of Paul Delaroche, he had entered the École des Beaux-Arts in 1839 and then exhibited regularly at the Salon—usually portraits and landscapes—since 1847.

21

Set against Vibert's worthy efforts, Manet's checkered artistic career must have seemed, to the extended Leenhoff family, rather scanty prospects on which to found a marriage.

When the meal was finished, Manet and Suzanne made their way to the Gare du Nord, from where they were waved off on the seven-hour train ride to Holland. The marriage, a civil ceremony, would be celebrated in Zaltbommel, Suzanne's hometown, on October 28. Manet's experience of Suzanne's family was scarcely more congenial than hers of his. He found her father, the organist and choirmaster Carolus Antonius Leenhoff, then fifty-six, "a typical Dutch

bourgeois,

sullen, fault-finding, thrifty, and incapable of understanding an artist."

22

If the newly married couple appeared to be dogged by problems with their in-laws, one person at least envied Manet his relationship. The raddled Baudelaire, who had neither met Suzanne nor even known of her existence, was surprised to learn of the wedding. Manet seems to have kept his domestic life a secret, for some reason, from even his closest friends. "Manet came round to tell me the most unexpected news," Baudelaire wrote to a mutual friend on the day Manet departed for Zaltbommel. "He leaves tonight for Holland, from where he will bring back his wife. He makes various excuses, however, since it seems his wife is beautiful, very kind, and a very great artist. So many treasures in a single female, isn't that quite monstrous?"

23