The Judgment of Paris (36 page)

If all went according to plan, therefore, visitors to the Universal Exposition in the Champ-de-Mars would only have a short walk across the Pont de l'Alma to study the works of what a newspaper called "the two ringleaders of Realism."

10

However, Manet faced a number of hurdles in getting his exhibition off the ground. He required the consent not only of Pomereu-d'Aligre and the Prefect of Police but also, critically, of his mother. Courbet was planning to spend as much as 50,000 francs on his exhibition, but he could well afford this huge sum: following his triumphs in Trouville in 1865, he had enjoyed another lucrative spell on the Normandy coast, this time at neighboring Deauville. But Manet, with no such commercial success behind him, was entirely dependent on his mother's purse strings. "Manetmaman" needed some persuading about the benefits of so costly an enterprise. She was no skinflint, living in grand style in her apartment in the Rue de Saint-Petersbourg, where she hosted her own female guests at soirées on Tuesdays and received the friends of her three sons—earnest young men such as Fantin-Latour and Zacharie Astruc—on Thursdays. She also doled out enough money to allow Édouard to keep himself in the style to which he was accustomed. Recently she had calculated that between 1862 and 1866 she had paid him a total of 80,000 francs, an average of 20,000 per year—a truly immoderate sum considering that doctors earned an annual income between 6,000 and 15,000 francs and highly skilled engineers between 10,000 and 20,000."

11

It seems to me high time to call a halt on this ruinous downhill path," she had wearily concluded after this depressing study of the account books.

12

Yet suddenly Édouard was demanding 18,000 francs to mount an exhibition of the very same canvases that had brought him, over the previous four years, little more than public humiliation and one corrosive review after another.

In an indication of her faith in the talents of her eldest son, Eugénie Manet agreed to finance the project. However, she handed over the funds on one condition: in order to save money, Édouard and Suzanne were to vacate their lodgings in the Boulevard des Batignolles and move into her apartment in the Rue de Saint-Petersbourg. A short time after the

Jour de I'An,

Suzanne therefore found herself sharing living quarters with her formidable and disapproving mother-in-law. Suzanne's own generosity and faith in the talents of her husband were indicated by the fact that she too had consented to this plan.

T

HE

JOUR DEL 'AN

HAD not always been celebrated on the first of January. Under the Julian calendar used in Europe throughout the Middle Ages, New Year's Day had fallen around the time of the spring equinox, on March 25. In 1564, however, King Charles IX of France signed the Edict of Roussillon, declaring the first of January to be the start of the calendar year and, according to legend, causing much confusion among those accustomed to celebrating

the Jour de I'An

at the end of March. A folk tradition soon arose in which those caught unaware by the calendar switch became, on the first of April, the butts of practical jokes. This custom of playing pranks on the first of April continued long after everyone in France acclimatized to the new calendar; one of the most popular involved sticking a paper fish to the back of an unwary friend and, when the trick was discovered, shouting "Poisson d'Avril!"—a catchphrase that became synonymous with the day. The first of April was therefore a date when one needed to be on guard to avoid becoming the "April Fish," an expression that became to the French what "April Fool" was to the English.

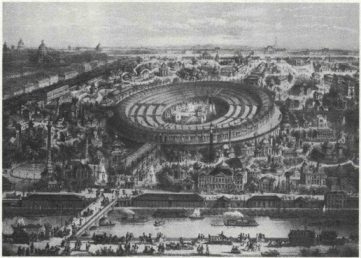

The crowds assembled in the Champ-de-Mars on the first of April in 1867 could have been forgiven for suspecting themselves of having become April Fish, the victims of some cruel prank. For the previous few months the weather in Paris had been atrocious, with constant rains turning the Champ-de-Mars into a quagmire and preventing the 10,000 workmen on the site from completing their tasks. This dire weather, along with various other delays and impediments, meant barely half the goods to be exhibited at the Universal Exposition had reached Paris by the eve of its opening. Of those crates that had arrived, only a fifth had actually been unpacked, let alone seen their contents assembled and displayed in the Palais du Champ-de-Mars. The opening ceremony, conducted by Emperor Napoléon on a muddy fairground amid packing cases, tarpaulin-shrouded exhibits, and crews of frantic workmen, therefore seemed something of a mockery. As one observer later wrote, the grand opening resembled the baptism of "a sickly child which seems born only to die."

1

In the first nine days of the Universal Exposition only 38,000 people paid to enter the Palais du Champ-de-Mars. Over the ensuing weeks, however, hundreds of tons of goods from the far-flung corners of the earth arrived in Paris by river, road and rail, followed by visitors in their hundreds of thousands. In the following months, Paris played host to the Czar of Russia, the Emperor of Austria, the King of Prussia, the Sultan of Turkey, the Pasha of Egypt, the King of Portugal, and the brother of the Mikado of Japan. By early summer the Universal Exposition had become exactly what Louis-Napoléon had promised, the grandest spectacle the world had ever seen.

With 50,000 exhibits, the Universal Exposition of 1867 had more than double the number shown in Paris in 1855. Most of these were exposed in a series of galleries arranged in concentric ovals around the inside of the Palais du Champ-de-Mars, which was bisected by long corridors radiating outward from a central garden. Visitors entering through the main door, on the side closest to the Seine, passed along the 200-yard-long Grand Vestibule, with the numerous galleries of French exhibits on the left and those of Great Britain and Ireland on the right. Roughly a third of the space inside the oval was devoted to French exhibits, but room was also reserved for the wonders of countries such as Brazil, Tunisia, Egypt, Siam, Morocco, China and Persia. Many thousands of items were on display, from tooth powder and sewing-machine needles to steam boilers and combine harvesters.

2

The art critic Edmond About claimed that visitors could see "all the most astonishing things that men and gods have created, the marvels of nature, the wonders of industry, the miracles of art!"

3

Among the new inventions were a typewriter, a phonograph, a tire made from rubber, a refined hydrocarbon oil called petroleum, and aluminum, a lightweight metal which so impressed the Emperor that he ordered a dinner service made from it. Other inventions included a high explosive called dynamite, created by a Swedish engineer named Alfred Nobel, and a new piece of furniture from America, the rocking chair. Displayed as well was a brass horn,

le saxophone,

invented by Napoléon Ill's Belgian-born Imperial Instrument Maker, Adolphe Sax.

The Universal Exposition of 1867

The theme of the 1867 Universal Exposition was "objects for the improvement of the physical and moral condition of the masses"—a timely topic given that less than two weeks after the exhibition opened Karl Marx arrived at his publishers in Hamburg with the finished manuscipt of

Das Kapital

under his arm. However, only 769 of the items on display were actually dedicated to improving the condition of the masses; the remainder were given over to more frivolous sights. As the correspondent for

The Times

reported, sightseers were treated to "a collection of all that is old or new, all that is prodigiously big or infinitesimally small, the preciously rare or the merely odd—all that may be more or less worth seeing, and with it also not a little which many a man of taste would be anxious to avoid."

4

There were Oriental dancing girls, Chinese slaves with bound feet, the bones and teeth of extinct mammals, and an Egyptian mummy that was ceremonially unwrapped before a paying audience that included Théophile Gautier. Visitors could have their photographs taken in special booths, purchase exotic refreshments such as caviar from Russia and smoked beaver tails from Canada, or take a ride in a hydraulic lift that carried fairgoers to an observation platform sixty-five feet above the ground. Outside the hall, the

Cileste,

a balloon owned by Nadar, took paying passengers for ascents over the Champ-de-Mars, while new pleasure boats called

bateaux-mouches

transported them on excursions along the Seine.

If they craved further entertainment, visitors to the Universal Exposition could simply have strolled the streets of Paris, transformed utterly since Louis-Napoléon came to power less than two decades earlier. Much broader than the twisted medieval streets they replaced, these new boulevards included the 140-yard-wide Avenue de l'Imperatrice, which cut a majestic swath through the wealthy Sixteenth Arrondissement from the Arc de Triomphe to the Bois de Boulogne, an enormous park where, on orders of the Emperor, 400,000 new trees had been planted. An equally impressive attraction lay beneath the spacious boulevards. In the first half of the nineteenth century, rainwater and sewage had flowed freely through the streets of Paris, flooding cellars, polluting the Seine and promoting disease. To remedy the situation, Baron Haussmann and his chief engineer, Eugène Belgrand, had constructed 200 miles of sewers, an efficient new system of gravitational tunnels that conducted the waste safely out of Paris and discharged it into the Seine. Tickets to view these tunnels were in great demand during the Universal Exposition, with thousands of people passing through the entrance in the Boulevard de Sebastopol and descending into the eerie, echoing labyrinth.

For those who managed to exhaust these seemingly limitless pleasures, the Salon of 1867 opened in the Palais des Champs-Élysées on April 15, a fortnight earlier than usual. The annual exhibition had not been staged without the usual turbulence. Elections for the Selection Committee, held in March, produced a jury virtually identical to that responsible for the International Exhibition of Fine Arts. The results of the deliberations were therefore predictably harsh. "Never in the memory of artists has a jury been more severe," wrote Castagnary in

La Liberté,

a journal whose provocative motto was "Death to the Institut de France." "Out of 3,000 artists who sent their work," he reported, "2,000 have been refused."

5

In fact, only 625 paintings were shown in the 1867 Salon. Édouard Manet had not bothered to submit any work, but many of his friends received the familiar bad news. Among the thousands of canvases returned to their owners with a red stamp on the back were ones by Renoir, Pissarro and Cézanne. The latter was cruelly mocked in

Le Figaro

(which dubbed him "Monsieur Sesame") as someone whose paintings were "worthy of exclusion from the Salon."

6

Undaunted, Cézanne (by this time sharing an apartment in the Batignolles with Émile Zola and his mother) began executing a canvas whose subject was disconcerting even by his own standards. Called

L'Enlevement

("The Abduction"), it was a brutal reworking of Cabanel's

Nymph Abducted by a Faun,

a work owned by the Emperor.

Also among the 1867

refusés

was Claude Monet. His eight-foot-high painting begun at Ville-d'Avray,

Women in the Garden,

was turned down by the jury, as was a seascape called

Port of Honfleur.

The rejection came as an unpleasant shock for Monet after his previous triumphs at the Salon in 1865 and 1866. However, one of the jurors, Jules Breton, explained that he had voted against Monet precisely because the young painter had been enjoying success. "Too many young people think only of pursuing this abominable direction," Breton complained. "It is high time to protect them and to save art."

7

The abominable direction to which Breton referred was Monet's lack of detail and finish. "It really is appallingly difficult to do something which is complete in every respect," Monet had written to Bazille a few years earlier, "and I think most people are content with mere approximations."

8

If this statement voiced the artistic creed for the Generation of 1863, many jurors desired something more than these "mere approximations"—something more than blurry impressions of gardens or beaches whose lack of fine detail mirrored, in the opinion of Breton and others, an absence of either moral integrity or narrative content.