The Judgment of Paris (42 page)

Manet was full of congratulations for his friend's robust defense. "I must say that someone who can fight back as you do must really enjoy being attacked," he wrote after the preface appeared in print.

20

He recognized, of course, that Zola's project was entwined with his own: "You are standing up not only for a group of writers," he wrote, "but for a whole group of artists as well."

21

But if Manet's portrait was to show both his gratitude to and his solidarity with Zola, his choice of a subject was a controversial one. He was proposing to place before the 1868 jurors—and then, if all went well, before the members of the public—the image of French literature's greatest

enfant terrible.

Portrait of Émile Zola

was made even more provocative by its conspicuous inclusion of a particular prop. Zola, who posed for the portrait over the course of several months in Manet's studio, was depicted sitting at a desk with a book in his hand and a number of pictures pinned to the wall. One of these pictures featured the unmistakeable image of Victorine posing as

Olympia

—a sight bound to raise eyebrows during the jury sessions. In a witty visual joke, Manet altered Victorine's eyes so that they directed themselves at the seated figure of Zola, her defender and champion. He had therefore given his most controversial work a pride of place in both his studio and his portrait of Zola. And he proposed to smuggle back into the Palais des Champs-Élysées the inflammatory image of Victorine reclining naked on her pillows.

More than 800 painters gathered to cast their ballots for the 1868 jury, almost seven times the number who had voted a year earlier.

22

There was much frenzied politicking by the teams of candidates as campaigning continued right up to the door of the Palais des Champs-Élysées. The atmosphere was later described by Zola, who wrote that voters were "pounced upon by men in dirty smocks shouting lists of candidates. There were at least thirty different lists . . . representing all possible cliques and opinions: Beaux-Arts lists, liberal, die-hard, coalition lists, 'young-school' lists, and ladies' lists. It was exactly like the rush at the polling booths the day after a riot."

23

The result of the wider suffrage and the campaigns by painters such as Courbet produced a jury that, after the dust had settled,appeared to differ very little from those of the previous few years. Each of the twelve painters elected for service in 1868had served on at least one previous jury, though Cabanel and Gérôme, who normally polled at the top of the list, were placedonly seventh and twelfth respectively. The man who drew the most votes, by a substantial margin, was Daubigny, a member ofCourbet's slate for whom more than half of all voters had ticked. He had been a popular choice among many of the younger artists,such as Pissarro and Renoir, who were voting for the first time, and who had appreciated the support of this "man of heart"against his more conservative colleagues on the Jury of Assassins in 1866. However, the only other member of Courbet's partyto get himself elected was Charles Gleyre, and the voters returned several prominent members of the Jury of Assassins, includingBaudry and Breton.

Perhaps the biggest surprise of the voting was that Meissonier failed to find special favor with the electorate, falling short of the 275 ballots required for elevation onto the jury. Despite his towering reputation, enhanced over the previous few months by both the Universal Exposition and the sale of

Friedland,

he finished only fifteenth, which gave him a position as one of the alternates. His disenchantment with the Salon, where he had not stooped from his Olympian heights to show work since 1865, coupled with his lack of enthusiasm for the invidious task of serving on the jury, meant he had not actively campaigned for votes. Even so, such a modest showing was a humiliation for the man hailed as Europe's greatest artist. Many of the younger artists who had been enfranchised for the first time, and who were struggling to get their work displayed, clearly did not regard the stupendously successful Meissonier as someone who might best understand their aims or represent their interests.

Meissonier's immediate response was to resign from his position as an alternate. This indignant rejection of the decision of his peers appears to have won him few friends, especially among the younger painters; in fact, it seems to have been a turning point in his career. By 1868 he was fast becoming a marked man. His enormous success and conspicuous prosperity meant that the younger generation—and in particular propagandists for the Generation of 1863 such as Zola and Zacharie Astruc—regarded him as a giant to be slain, together with the two other artistic leviathans of the age, Cabanel and Gérôme. The stratospheric prices fetched by Meissonier's paintings as well as his abundant critical laurels jarred all too conspicuously with, for example, Manet's collection of grisly reviews and his stack of unsold canvases, while the painters of the Generation of 1863 found his painstaking technique difficult to appreciate. Astruc had assailed him as early as 1860, disparaging his work for its supposed creative destitution. After seeing an exhibition of Meissonier's paintings in the Galerie Martinet, Astruc sneered that the work demonstrated "neither movement nor heat nor spirit nor imagination, but only cold-bloodedness, tenacity and, embroidering the whole, a patience for work verging on the phenomenal."

24

The ground had begun subtly to shift beneath Meissonier's feet. He may have been more sympathetic than most of his colleagues on the jury to the techniques and styles of the

refuse's

of 1863 and 1866; yet the "new movement" praised by Zola—the striving for an abstraction of visual effect through the apparently spontaneous application of paint—was as far removed as could be imagined from the severe precision of his own style. Gautier had once enthused over how Meissonier painted so realistically that the viewer fancied he could see his figures' lips move.

25

By the middle of the 1860s this sort of finicky exactitude was suddenly, in the eyes of certain painters, merely the stock-in-trade of the technically flawless but creatively barren alumni of the École des Beaux-Arts. Even Delacroix had once admitted in his journal, with pointed reference to Meissonier, that "there is something else in painting besides exactitude and precise rendering from the model."

26

Meissonier suddenly found himself in danger of being assailed for the very techniques which had won him such fame in the first place.

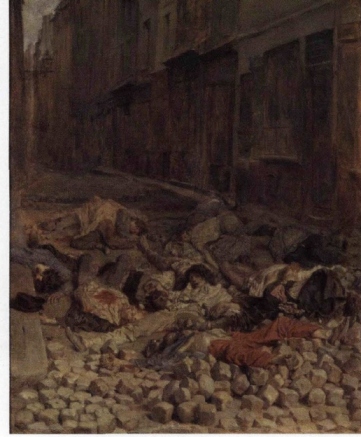

1A.

Remembrance of Civil War

(Ernest Meissonier)

IB.

Liberty Leading the People

(Eugène Delacroix)

2A.

The Emperor Napoléon III at the Battle of Solferino

(Ernest Meissonier)

2B.

The Campaign of France

(Ernest Meissonier)

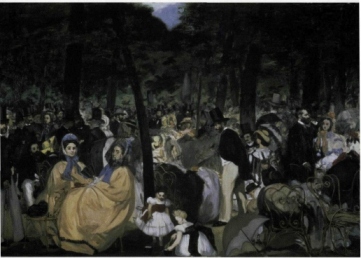

3A.

Music in the Tuileries

(Édouard Manet)

3B.

A Burial at Ornans

(Gustave Courbet)