The Judgment of Paris (5 page)

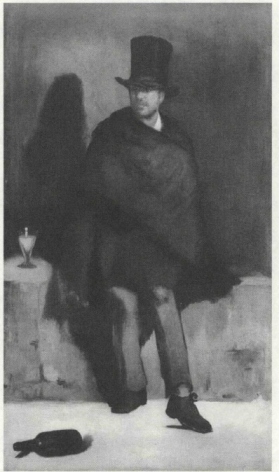

For this great exhibiton in 1859 Manet had submitted, not one of his Renaissance-inspired mythological canvases, but

The Absinthe Drinker,

the model for which was a rag-and-bone man named Collardet whom he had met one day while sketching in the Louvre. The presence in the Louvre of a rag-and-bone man testified to how interest in fine arts crossed all social boundaries in Paris, and how in some years a million people—out of a city of only 1.7 million—could visit the Salon. Yet Manet did not depict Collardet as a connoisseur of art. He posed him beside an overmrned bottle with a glass of absinthe at his elbow, a stovepipe hat perched on his head. The result was a modern-day Parisian, a rough-looking drunkard such as one might have seen after dark in the Batignolles.

Absinthe was a greenish alcoholic beverage so popular with Parisians that they spoke of the "green hour" in the early evening when they sat imbibing it in cafés. However, besides being seventy-five percent proof, the drink was flavored with wormwood, an herb whose toxic properties caused hallucinations, birth defects, insanity and, according to the authorities, rampant criminality. Manet's solitary figure loitering menacingly among the shadows must have seemed an all-too-graphic illustration of the consequences of its consumption. At least as unsettling as the subject matter, though, was the style of the work. Two years earlier a critic had praised Meissonier for painting his

bonshommes

so realistically that their lips appeared to move.

11

Such mind-boggling manual dexterity and painstaking dedication to minutiae were entirely absent from Manet's work. He applied his paint thickly and in broad brushstrokes, suppressing finer details such as the facial features of his reeling drunkard and taking instead a more abstract approach to visual effects. Ushered into Manet's studio, Couture ventured the opinion that his former student had produced only "insanity."

12

The jury for the 1859 Salon was no more impressed, promptly rejecting the work. It appeared to them not only to lack any sort of finesse but also to celebrate the same debauched low life as the poems in Baudelaire's

Les Fleurs du mal,

one of which, "The Wine of the Ragpickers," recounted the antics of a drunken rag-and-bone man as he staggered through "the mired labyrinth of some old slum / Where crawling multitudes ferment their scum."

13

At the next Salon, in 1861, Manet submitted, and had accepted, two canvases, both less controversial in theme if not in technique:

The Spanish Singer,

showing a model in Spanish costume seated on a bench and playing a guitar; and a portrait of his mother and father, the latter of whom had by this time been paralyzed and robbed of his speech by a stroke (a tragedy alluded to in the grim, downcast expressions of both his parents). The two paintings received contrasting receptions when they were placed on show with almost 1,300 others. While

Portrait of M. and Mme. Manet

was roasted by the critics—one wrote that the artist's parents "must often have rued the day when a brush was put into the hands of this merciless portraitist"

14

—his guitar-strumming Spaniard, inspired by Velázquez, caught the eye of Théophile Gautier, the friend and admirer of Meissonier.

The Absinthe Drinker

(Édouard Manet)

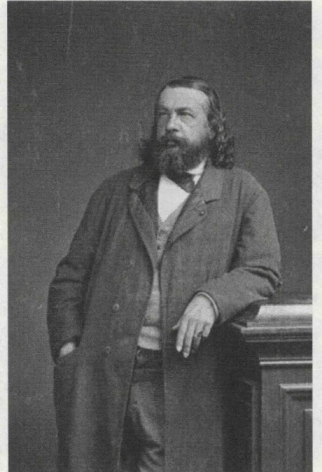

The fifty-year-old Gautier, who smoked a hookah and favored wide-brimmed hats and dramatic capes, was a scourge of bourgeois respectability and a champion of such rebels as Hugo, Delacroix and Baudelaire, the latter of whom had dedicated

Les Fleurs du mal

to him. Generous and sociable, he entertained every Thursday evening at his riverfront house in Neuilly-sur-Seine, a pleasant suburb to which luminaries such as Gustave Flaubert would go to recline on Oriental cushions among their host's collection of cats, books and cuckoo clocks. A poet and novelist in his own right, he had become, in the words of a fellow critic, "the most authoritative and popular writer in the field of art criticism."

15

A favorable word from Gautier could make the reputation of a painter, with the result that the flamboyantly attired critic was daily bombarded with letters from artists pleading for reviews.

Théophile Gautier (Nadar)

"Carambaf"

wrote Gautier in

Le Moniteur universe!,

the official government newspaper, after seeing Manet's

The Spanish Singer.

"There is a great deal of talent in this life-sized figure, which is painted broadly in true colors and with a bold brush."

16

This seal of approval meant the canvas was singled out for public attention, soon becoming so popular with Salon-goers that it was placed in a more conspicuous location. An award even came Manet's way: an Honorable Mention. Still more gratifying, perhaps, was its reception by other young artists, who were intrigued by its vigorous brushwork, its sharp contrasts of black and white, and a slightly slapdash appearance that seemed to oppose the highly polished, highly detailed style of so many other Salon paintings.

The Spanish Singer

was painted in such a "strange new fashion," according to one of them, that it "caused many painters' eyes to open and their jaws to drop."

17

Though he had yet to sell a single painting, Manet, at the age of twenty-nine, seemed emphatically to have arrived.

Édouard Manet's forebears on his father's side had been, if not quite aristocrats, then at least respectable members of the gentry. In the middle of the eighteenth century, Augustin-François Manet, the painter's great-great-grandfather, had been the local squire in Gennevilliers, a town on the Seine a few miles northwest of Paris. His son Clement, Manet's great-grandfather, had served King Louis XVI as treasurer for the Bureau des Finances for Alencon, north of Le Mans. Shrewdly switching sides after King Louis lost his head, he swore the civic oath, gobbled up even more land in Gennevilliers, and in 1795 became the town's mayor. His son, likewise named Clement, followed in his footsteps, serving his own term as mayor from 1808 to 1814.

Fifty years on, the family fortune consisted of two hundred acres of land in the suburbs of Gennevilliers and neighboring Asnières-sur-Seine, together with a house in Gennevilliers where the family spent part of every summer in order to escape the heat of Paris. Édouard Manet became an heir to this sizable estate in the year following his victorious Salon: still disabled by his stroke, Auguste Manet died in September 1862, at the age of sixty-six.

18

Édouard was due to receive a third of the legacy, splitting with his two younger brothers, Gustave and Eugène, the proceeds of lands worth as much as 800,000 francs—a huge fortune—if sold on the open market.

19

These ancestral acres lay fewer than five miles from Manet's modest studio in the Batignolles. Asnières and Gennevilliers were within easy reach of Paris by train, the former only a ten-minute ride from the Gare Saint-Lazare. Gennevilliers was a mile or so to its north, on a low-lying plain whose rich soil, fertilized by sewage from Paris, allowed numerous market gardens to grow vegetables for the dinner tables of the capital. Since the arrival of the railway in Asnières in 1851, however, another industry had developed. The Seine was two hundred yards wide at Asnières and, as such, perfect for sailing and rowing. A sailing club, Le Cercle de la Voile, had been founded, and on weekends during the summer Parisians descended on Asnières in the thousands to rent rowboats, swim in the river, picnic on the bank, or avail themselves of attractions such as the Restaurant de Paris, which served food and drinks on a large terrace overlooking the river. These crowds were tempted, according to a novel of the day, "by the idea of a day in the country and a drink of claret in a cabaret."

20

Édouard Manet had arrived among this brigade of daytrippers one day in the late summer or early autumn of 1862, around the time of his father's death. He was in the company of a friend named Antonin Proust, the son of a politician and a fellow pupil from Couture's studio. More than thirty years later, Proust was to remember how the two young men had sunned themselves on the riverbank, watching skiffs furrowing the Seine and, in the distance, female bathers disporting in the shallows. Their talk turned naturally enough to painting, in particular to the nude. Nudes always attracted a great deal of attention at the Salon. Few things impressed the critics more than a well-turned heroic male nude, the execution of which, in the style of either the Ancients or the masters of the Italian Renaissance, made the strictest trial of an artist's abilities. Even more highly prized by the critics were female nudes.

21

Such paintings were venerated so highly by the Académie des Beaux-Arts that painters referred to a nude study as an

académie.

22

Female nudes were not meant to titillate the viewer with their sensuality but to give physical form to abstractions such as ideal beauty or chaste love. What could happen if an artist strayed from portraying this ideal of beauty or virtue in favor of a more unvarnished illustration of the unclad female form had been demonstrated by French art's greatest

bête noire,

a blustering, bellicose painter named Gustave Courbet. A self-proclaimed socialist and revolutionary who had founded a school of painting he called Realism, Courbet had exhibited at the Salon of 1853 a canvas called

The Bathers,

which featured two young ladies in the woods, one sitting half-undressed beside a stream, the other presenting to the spectator, as she stepped naked from the water, copious layers of fat and a bountiful posterior. The critics were disgusted by such a show of lumpy female flesh; even Delacroix lamented Courbet's "abominable vulgarity" in depicting what he called "a fat bourgeoise."

23

The canvas was swiftly removed from view by a police inspector, but not before the emperor Napoléon III was rumored to have struck it a sharp blow with his riding crop.

So far in his career Manet had not sent a nude, either male or female, to the Salon. But the sight of Parisians taking a dip in the Seine reminded him of Titian's

Le Concert champêtre

in the Louvre, a painting that featured two women and two men in a rural landscape, the women nude, the men fully clothed.

24

Proust remembered how Manet stared at the bodies of the women leaving the water before remarking: "It seems that I must paint a nude. Very well, I shall paint one."

25

However, he explained to Proust that his own painting would include "people like those you see down there"—modern-day Parisians instead of the elegant sixteenth-century Venetians of Titian's work. "The public will rip me to shreds," he mused philosophically, "but they can say what they like." Whereupon, according to Proust, the young artist gave his top hat a quick brush and clambered to his feet.

26

The notion of painting modern-day Parisians was a relatively new one, though as long ago as 1824 the novelist Stendhal had urged artists to depict "the men of today and not those who probably never existed in those heroic times so distant from us."

27

This imperative had been adopted more recently by Manet's teacher, Thomas Couture. Though his own most famous work was

The Romans of the Decadence,

a historical tableau showing the moral decline of the Roman Empire, Couture had urged his students to take their subjects from nineteenth-century France. "I did not make you study the Old Masters so that you would always follow trodden paths," he told his pupils before exhorting them to represent such contemporary sights as workmen, public holidays and examples of modern technology such as locomotives. Artists of the Renaissance did not paint such sights, he pointed out, for the sole reason that in those days they did not exist.

28