The Kennedy Half-Century (78 page)

Read The Kennedy Half-Century Online

Authors: Larry J. Sabato

Tags: #History, #United States, #General, #Modern, #20th Century

Bill Clinton truly was no John F. Kennedy, and Kennedy was not Clinton’s doppelgänger. Clinton was Clinton, with all the good and bad his own persona dictated. Judging by his postpresidential popularity and the positive retrospective view most people have adopted about his policies (as opposed to his regrettable personal failings), Clinton carved a distinctive path. It was a legacy quite different than John Kennedy’s, but still agreeable to the electorate for the most part.

Presidents and presidential candidates often express admiration for certain White House predecessors. Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln are

relatively uncontroversial choices (slave ownership aside for the first two). A couple of sons of former presidents, John Quincy Adams and George W. Bush, had the fondest affections for their fathers. Men who succeeded to office through the death of a president will invoke their patron’s name habitually. Occasionally, a chief executive will make a past president a role model for a combination of political and policy reasons, as Gerald Ford did with Give-’Em-Hell Harry Truman or as Ronald Reagan chose to do with small-government proponent Calvin Coolidge. Youthful idolization led Bill Clinton back to John Kennedy.

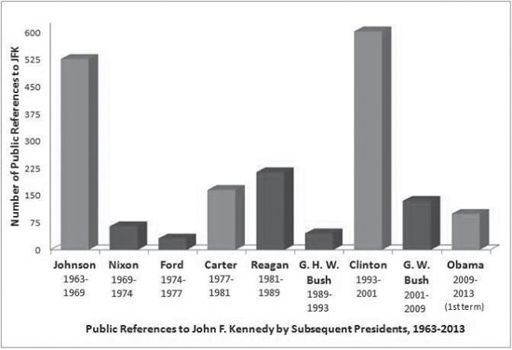

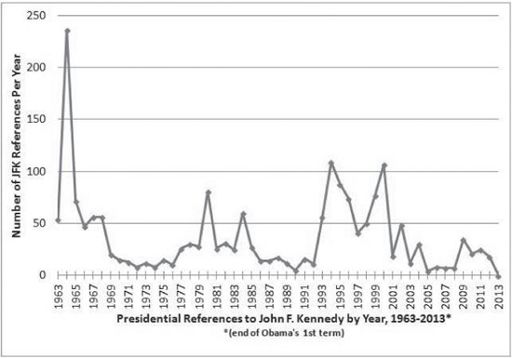

Citing President Kennedy has been a staple for all modern Oval Office occupants, of course. A couple of graphs can illustrate the number of times every post-JFK president invoked Kennedy in public. The top chart shows the total number of times each president publicly mentioned JFK in speeches, press conferences, and the like, while he served in the White House. The second chart plots the same thing, but from year to year: As one would expect, Lyndon Johnson mentioned the man who made him vice president and originated many of his programmatic objectives with great frequency. JFK’s rival, Richard Nixon, barely cited JFK, and neither did Gerald Ford. The first Democratic president since LBJ, Jimmy Carter, brought Kennedy into play more than Nixon and Ford, but less than a third as often as Johnson. John Kennedy was linked frequently to Reagan’s central proposals so there was a JFK revival in the 1980s. George Bush the senior rarely referred to Kennedy. And then along came Bill Clinton, who managed to summon the Kennedy name and legacy so often he exceeded Johnson’s mountainous total.

This was a genuine impulse in Clinton, but it was also a conscious strategy by a young Democratic candidate and president to link himself to the Kennedy era’s hopes and dreams—and older voters’ memories of them. Clinton’s mainly popular two-term presidency is a measure of his success in capitalizing on JFK’s style and rhetoric.

ah

Perot was the second most successful independent presidential candidate in U.S. history, after former president Theodore Roosevelt, who garnered 27.4 percent of the vote in 1912 as the candidate of the Progressive or “Bull Moose” Party.

19

G. W. Bush: Back to the Republican Kennedys

A freakishly close vote in Florida set the stage for one of the most contested elections ever. Once the November vote was counted, Vice President Al Gore, the Democratic nominee, led Republican nominee George W. Bush, the Texas governor and son of President George H. W. Bush, by 540,000 votes in the national tally (out of 105 million cast). But in the all-important electoral vote, Gore had 267, three short of victory, Bush had 246, and the decisive 25 electoral votes were the Sunshine State’s—where Bush and Gore were virtually tied. It took a hotly disputed recount and ultimately a divisive Supreme Court decision in

Bush v. Gore

1

to resolve the matter. Democrats viewed the Court ruling as partisan, with the five most conservative justices siding with Bush against the four more liberal justices’ preference for Gore, but in the end, Bush was declared the winner by an astonishingly tiny 537 votes in Florida—2,912,790 for Bush to 2,912,253 for Gore. This gave Bush a final electoral count of 271 votes, one more than the minimal majority needed for election.

2

Thus, the offspring of president number 41 became president number 43, a Bush restoration after just eight years. Compare this to the twenty-four years that separated the two chief executives from the Adams family, John Adams who left office in 1801 and John Quincy Adams who entered the White House (after losing the popular vote) in 1825. Both of the Adamses served only one term, but George W. Bush would get two. The dozen years of Bush White House occupancy compares to less than three for the Kennedy family. The Bush family also accumulated eight years in the vice presidency (the senior Bush), fourteen years in the governorships of Texas and Florida (George W. and Jeb), ten years in the Senate (grandfather Prescott of Connecticut), and four years in the House (Bush senior). The Kennedys have had no governorships, but three senators (John, Robert, and Edward) plus scattered House service by several family members and a lieutenant governorship (Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, Bobby’s daughter, in Maryland).

There is no real comparison: The more successful family dynasty by far, at

least to this point, has the surname of Bush. No one would have guessed this in the 1960s, and it is one of history’s sleight of hand tricks. Demography has played as much a part as destiny. In population, wealth, and influence, the Sunbelt has come to dominate the Frostbelt, and thus has the Texas house of Bush outstripped the Massachusetts line of Kennedys. Patriarch Joseph Kennedy’s dreams of a long period of Kennedy dominance were dashed by war (Joe Jr.), bullet (Jack and Bobby), scandal (Teddy), and accident (John Jr.). Younger generations of Kennedys, including new congressman Joseph Kennedy III of Massachusetts, may try to even the score, though the Bushes have potential competitors, too, such as Jeb’s politically active son George P. Bush—and Jeb Bush himself.

Yet, fifty years on, the short Kennedy presidency is far more admired by the public than either of the Bush tenures, and the iconic legacy of JFK’s short White House stay greatly overshadows three full terms of the Bush family. George W. Bush was superficially a good deal like John F. Kennedy. Both had famous and powerful fathers, came from well-heeled, privileged backgrounds, had Ivy League educations, were elected president in squeakers, and saw foreign policy dominate their terms. Yet even Bush jokes frequently about his lack of eloquence and frequent malapropisms. Jack and Jackie Kennedy were the life of the party and led the nation culturally from the White House. Though gracious hosts, George and Laura Bush were famous for going to bed by 9:30 P.M. whenever possible. It may well be that Bush’s serious, sober personal style was preferable to JFK’s wild living for governance. Still, the public’s imagination is rarely captured by bland temperance.

Concerning his presidential agenda and the Kennedys, George W. Bush was more like Ronald Reagan than his father. The second Bush was a determined tax-cutter, unlike his dad, who had famously violated his campaign pledge, “Read my lips, no new taxes,” by raising taxes during his term. In seeking across-the-board cuts as part of his early legislative program, Bush copied Reagan in citing JFK before Congress and on the stump. The tax cuts were needed, said Bush, “to, in President Kennedy’s words, ‘get this country moving again.’”

3

In his most significant early achievement—but one with damaging consequences for the burgeoning national debt—Bush won $1.35 trillion in tax cuts, which he supplemented with still more tax breaks in both 2002 and 2003.

4

Other than tax cuts, the closest parallel in the Bush presidency to JFK’s was a militarily assertive foreign policy. Just as with Kennedy at the Bay of Pigs, the Bush administration was not prepared for its first-year crisis, the terrorist attacks on September 11.

5

But in the aftermath of failure, both administrations were transformed; they reevaluated and recalibrated to prepare for the crises to come. In Bush’s case, the decision to strike back in Afghanistan

(and later, much more controversially, in Iraq) as well as the actions taken to protect air travel and the homeland defined his White House years. Kennedy and all Cold War presidents were able to use the clear and present danger of a well-defined threat (the Soviet menace) to marshal public opinion and congressional support for their goals. While it came at a high price, terrorism in the twenty-first century returned purpose and clarity to American politics—and restored a natural enemy—that had been lacking since the fall of the Soviet empire. The “axis of evil” (Iran, Iraq, and North Korea, along with terrorism generally) enabled Bush to focus his energies on enemies that unified Americans, at least temporarily. Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein became Bush’s Fidel Castro and Nikita Khrushchev.

In the view of many, though, this led to the kinds of excesses in the name of national security that had emerged during the Cold War era. The powers of the National Security Agency were broadened to permit eavesdropping on U.S. citizens and foreign nationals domestically, and the FBI’s powers were expanded in a wide-ranging new antiterrorism law, the PATRIOT Act.

6

The “imperial presidency” of JFK’s era was back, and civil liberties were restrained to meet the threat posed by another “ism”—terrorism this time rather than Communism. President Bush insisted that his national security reforms did not trample civil liberties in a manner reminiscent of the Cold War, and in his memoir,

Decision Points

, he specifically cited the excesses under the Kennedy administration: “Before I approved the Terrorist Surveillance Program, I wanted to ensure there were safeguards to prevent abuses. I had no desire to turn the NSA into an Orwellian Big Brother. I knew that the Kennedy brothers had teamed up with J. Edgar Hoover to listen illegally to the conversations of innocent people, including Martin Luther King Jr. Lyndon Johnson had continued the practice. I thought that was a sad chapter in our history, and I wasn’t going to repeat it.”

7

Bush was not so publicly critical of the Kennedys while in office, and certainly not in the opening stages of his administration. To the contrary, he believed his success in securing one of his major goals, an education law called No Child Left Behind, depended heavily on Senator Ted Kennedy. As governor of Texas, Bush had also skillfully wooed powerful Democrats such as Texas House Speaker Pete Laney and Lieutenant Governor Bob Bullock, so he had confidence his technique of bipartisan camaraderie might work in Washington.

For the first film screening in the new Bush White House, the president and Mrs. Bush chose

Thirteen Days

, a movie about JFK’s handling of the Cuban Missile Crisis. The guest of honor was Ted Kennedy, and he brought much of the family with him. The occasion was to prove the power of what President Bush’s press secretary, Ari Fleischer, called “the amazing soft power

of a kindly invite.” As Fleischer pointed out, Bush recognized “there were two Ted Kennedys. There was the Ted Kennedy that … could take to the floor of the Senate and give the most impassioned, powerful speech anyone has ever heard and he will fight you tooth and nail. The other Ted Kennedy was the one who will reach a compromise with you and reach across the aisle. Both Kennedys existed on any given day … Bush knew if he could get the compromising Kennedy to be with him, chances were very good that his legislation was going to make it through the Senate. Kennedy was that type of old bull.”

At the time, Bush insisted his gestures of friendship for Senator Kennedy had no connection to legislative deal making, but the ex-president’s memoirs noted, “The movie hadn’t been my only purpose for inviting Ted. He was the ranking Democrat on the Senate committee that drafted education legislation. He had sent signals that he was interested in my school reform proposal …” That night Bush told Kennedy he wanted to be known as “the education president” and emphasized, “I don’t know about you, but I like to surprise people. Let’s show them Washington can still get things done.” The next morning, a note from Kennedy to Bush arrived, reading in part, “Like you, I have every intention of getting things done … We will have a difference or two along the way, but I look forward to some important Rose Garden signings.”

8