The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara (47 page)

Read The Kidnapping of Edgardo Mortara Online

Authors: David I. Kertzer

When the Monsignor finally got out of jail, in June 1865, there still was no archbishop in Bologna to succeed the now long-dead Corsican cardinal. The government had refused to permit the Dominican to take office, and it was only in 1871 that Guidi finally renounced his appointment, never in those

years having set foot in his archdiocese. As a result, upon his release after three years in jail, Monsignor Canzi served six more years as acting archbishop of Bologna.

17

As for the Dominicans whom Father Feletti left behind, they too suffered. As the government of the new state gave up on its attempts to make peace with the ever-hostile Church, it resorted to tactics that Napoleon had employed at the turn of the century. In July 1866, Parliament passed a law suppressing religious orders and ordering the confiscation of their property. In December of that year, the remaining friars were forced to abandon San Domenico, leaving the bones of their founder behind. The entire convent was turned into a military barracks, while just three Dominicans were allowed to remain to oversee the church itself.

The following year, adding insult to injury, the city council changed the name of Piazza San Domenico to Piazza Galileo Galilei, honoring the Inquisition’s most eminent victim. In January 1868, a city councilor, decrying the presence in the square of the statue of Saint Dominic, which had looked down on the picturesque piazza since 1627, proposed replacing it with a monument to those men of Bologna who had died in the struggle to defeat papal power. That, as it turned out, proved a bit much for the members of the city council, and, by a vote of 31 to 7, Saint Dominic’s likeness was allowed to stand.

18

CHAPTER 23

New Hopes for

Freeing Edgardo

T

HE

M

ORTARAS HAD

put little hope in the Feletti trial. Neither Momolo nor Marianna had had a direct hand in bringing about the Inquisitor’s arrest, and even Momolo’s father’s plea to Farini, which had led to the friar’s jailing, had been aimed not at bringing Father Feletti to trial but at getting Edgardo back.

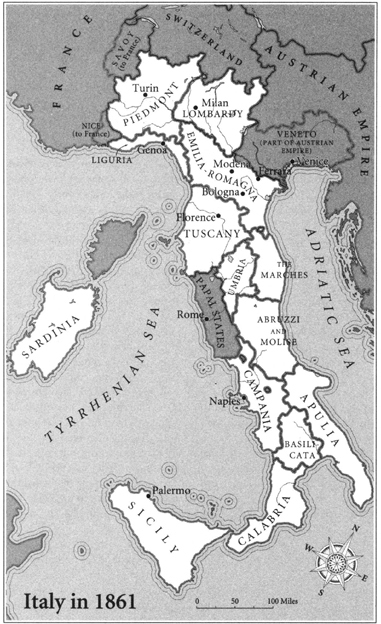

For the first several months after his son was taken, Momolo remained convinced that the Pope could be persuaded to return him. By the time he finally realized that Pius IX would never willingly give Edgardo up, the clouds of unification were already on the horizon. It was the beginning of the end of the Papal States. When papal forces and their Austrian protectors retreated from Bologna and Romagna in June 1859 and the new king and his prime minister, Count Cavour, prepared to send their troops southward into the Marches and Umbria, the status of the Papal States and the future of the Pope’s temporal power moved to center stage in European diplomacy. The Pope no longer enjoyed the position he had occupied but a few months before, when, ruling a sizable territory and backed by foreign armies, he could do as he pleased. Now, thought Momolo, whether Pius IX liked it or not, he would have to listen to the foreign powers whose deliberations would determine whether the Pope continued to have any land to rule at all.

In the fall of 1859, in the wake of the revolts in Romagna, Parma, Modena, and Tuscany, plans began to be made for a conference of European powers, to be held in Paris, to discuss the fate of Italy and the Papal States. France and Great Britain would be the two most influential participants.

All of Momolo’s efforts to follow the quiet diplomacy urged on him by Scazzocchio and other officers of Rome’s Jewish community had failed. Now living in Turin, he was increasingly influenced by the perspective of the Jews of Piedmont, whose public criticism of the Vatican contrasted with the role of humble supplicant assumed by Rome’s Jewish leaders. Papal rule, in the Piedmontese view, was an anachronism that the governments of the civilized world could no longer tolerate.

Momolo thus came to see the upcoming conference as his best hope for getting Edgardo back. In its November 28 issue, the Bologna newspaper

Gazzetta del popolo

reported hopefully: “The members of the Congress will probably be fathers of families themselves, and even those who aren’t will not remained unmoved by the pleas of a father who asks to be given back a son who was violently stolen from him by a government that the oppressed and outraged peoples have repeatedly expelled every time that it has been left unprotected by a foreign army.”

1

In December 1859, Momolo was in Paris, frantically trying to drum up support for his cause. But the issue that had been so much on the mind of the French ambassador to the Holy See the previous year, and that had irritated the Emperor himself, no longer drew much attention. The French already had more than enough to attend to in Italy, with the defeat of the Austrians in Lombardy, the demise of the Italian duchies, the fall of the old regimes in Romagna and Tuscany, and the uncertain future of the tottering kingdom of the Two Sicilies, not to mention the ticklish question of what to do about what remained of the Papal States.

Isidore Cahen, the

Archives Israélites

editor who had long championed the Mortara case, could see this even if Momolo could not. In January 1860, he described his recent meeting with Momolo, a man who seemed obsessed with the effort to get his son back: “We in Paris saw a father who was desolate,” wrote Cahen. “We listened to him, we saw the tears in his eyes, this husband whose wife is still sick from the blow that struck her. We felt that the scar was still open, and we didn’t have the courage to tell him how unlikely [diplomatic] intervention seemed to us.”

2

From Paris, Momolo went on to London, where he received the news that Father Feletti had been arrested. He met with Sir Moses Montefiore for the first time and addressed the Board of Deputies of British Jews, pleading with them to get the British government to bring the question of Edgardo’s plight before the upcoming congress. Momolo also met with Sir Culling Eardley, head of the Protestant Evangelical Alliance in Britain, who had campaigned so vigorously for Edgardo’s release. He met with members of the Rothschild family, who had not only been providing him with financial support but who, he hoped, could use their influence to help his cause at the congress. Yet, after all this campaigning, Momolo was disappointed. Because of the kaleidoscopic course of political events, the congress was called off, and his dreams of seeing the leading diplomats of Europe discuss his son’s kidnapping and devise a plan for the boy’s release came to nothing.

3

He returned, dejected and ill-humored, to Turin.

Although the Mortara case was no longer high on the European diplomatic agenda, it remained powerfully resonant among the Jews of Italy, Britain, and especially France. No journalist had crusaded for the Mortara cause more ceaselessly than Isidore Cahen in Paris. For the Jews to find themselves in the same conditions as in the Middle Ages, wrote Cahen, was intolerable. In much of the world, Jews remained subject to the whims of anti-Jewish government officials and exposed to demagogues who delighted in whipping the local rabble into anti-Semitic frenzies. In the wake of the Mortara affair, and with Momolo’s visit to Paris still fresh in their minds, a group of Jewish men met in Paris in May 1860, convinced of the need to create an international organization in defense of Jewish civil rights. There they founded what soon became the most important European organization of its kind, the Alliance Israélite Universelle, which still today has its headquarters in Paris.

4

Those who saw Momolo in this period found a man transformed by the horrors he had lived through over the past two years, a man aged, weighed down by worries. His business was ruined, and he lived on Jewish charity, money provided not only by the Rothschilds but by donations collected at synagogues throughout Europe. Returning to Italy, he testified before Magistrate Carboni, where he let some of his bitterness show, denouncing the former inquisitor’s claim about his son’s happiness in being taken from his parents, and about the Pope’s solicitude. But despite all this, while others had given up hope, Momolo still believed that one day he would be able to get Edgardo back.

In May, Giuseppe Garibaldi led his legendary thousand-man volunteer army by boat to Sicily, where he established rule over the island in the name—although against the wishes—of King Victor Emmanuel. The enlarged Garibaldian army began its march up the peninsula in August, and by early September had conquered Naples, center of the Bourbon court that ruled the kingdom of the Two Sicilies. The remaining Papal States fell to the Piedmontese forces shortly thereafter, leaving only the region around Rome to the Pope and his secretary of state.

With Victor Emmanuel’s forces moving so swiftly through the peninsula, and the Papal States crumbling, Momolo had new grounds for optimism. In August 1860, in a letter of thanks to the chief rabbi of the Alsatian city of Colmar, who had sent him the proceeds of his congregation’s collection, Momolo wrote: “The happy events that are taking place in Italy give me hope that the day is not far off when justice will be done and I will have my poor, dear little son back again.”

5

Rome’s fall now seemed imminent. And if Rome fell, what was to prevent the Mortaras from taking their child back? Officers of the newly formed Alliance Israélite Universelle kept a close watch on the development. On September 17, with Piedmontese troops beginning their march down from Romagna into the Marches and Umbria, they wrote to Count Cavour.

“Like all friends of progress and freedom,” wrote the organization’s president, Alliance members had been pleased to hear the reports that the French troops would soon be leaving Rome and that the Pope would no doubt flee as well. Yet they were concerned that the Pope, “moved by an exaggerated religious sentiment,” might try to take little Edgardo Mortara with him. The Alliance Israélite Universelle, he informed the Prime Minister, was “taking measures to protect this young child, who is today a Sardinian subject, now detained contrary to the eternal laws of nature and of God!” The Alliance “dares to hope,” the letter continued, “that with your refined spirit and your noble heart you will not forget the innocent victim of the cruelest persecution, despite the many important questions that will no doubt arise when the kingdom of Italy takes possession of the capital.”

Two weeks later, Cavour responded, assuring the Jewish organization that his government would do everything possible to see that the Mortara boy was returned to his family.

6

His letter was properly diplomatic, but he did not really think it likely that the Pope would be dislodged from Rome any time soon. The Prime Minister was, however, genuinely concerned for Edgardo’s fate. The following spring, when he had much else on his mind, and when the Mortara case no longer promised any diplomatic advantage, he sent a letter to Count Giulio Gropello, the Sardinian representative to the kingdom of Naples, reminding him of the boy’s abduction and the Pope’s refusal to budge. Cavour told the Count that he had recently received new pleas from the boy’s father, and expressed his enthusiastic support for Momolo’s request that his son be returned, reiterating his belief that the boy’s abduction was an offense against natural law. He noted, regretfully, that there was little he could do, for his government had no diplomatic relations with the Holy See. Cavour suggested that the French, on whose troops the Pope depended, might be able to act more successfully.

7

Just five weeks later, at the height of his fame and in the midst of his labors to build the new Italian nation, Cavour was suddenly struck ill and died. He was fifty years old.

Following his letter to Cavour in mid-September 1860, the president of the Alliance Israélite Universelle wrote to Momolo Mortara in Turin with the thrilling—if enigmatic—news that the Alliance had a plan of action in place for liberating his son: “This is what you have to do to find your son and get him back again. You must keep closely posted on events and get the best-informed people in Turin to let you know the time when the Pope is likely to fall. Then you will leave for Rome, and there you will speak to the friend whose name

we give you below. He is one of our coreligionists, and you will find that he will give you the most efficient support in Rome.” Just who this secret Jewish agent was in Rome, we do not know. The copy of the letter that remains in the Paris archives lacks it, and the original, which Momolo received, is long gone.

The letter went on to offer Momolo reimbursement for what it would cost him to leave his business and go to Rome, for “getting your child back is the cause of all Israel.… It goes without saying,” the Alliance president added, “that you must employ the greatest prudence in this delicate matter, the most absolute secrecy. Success depends on it.”

8