The King of Ireland's Son, Illustrated Edition (Yesterday's Classics) (12 page)

Read The King of Ireland's Son, Illustrated Edition (Yesterday's Classics) Online

Authors: Padraic Colum

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction

"And what sort of a man is your gossip, the Churl of the Townland of Mischance?" Gilly asked.

"An unkind man. Two youths who served me he took away, one after the other, and miserable are they made by what he did to them. I'm in dread of your being brought to the Townland of Mischance."

"Why are you in dread of it, Spae-Woman?" said Gilly. "Sure, I'll be glad enough to see the world."

"That's what the other two youths said," said the Spae-Woman. "Now I'll tell you what my gossip the Churl of the Townland of Mischance does: he makes a bargain with the youth that goes into his service, telling him he will give him a guinea, a groat and a tester for his three months' service. And he tells the youth that if he says he is sorry for the bargain he must lose his wages and part with a strip of his skin, an inch wide, from his neck to his heel. Oh, he is an unkind man, my gossip, the Churl of the Townland of Mischance."

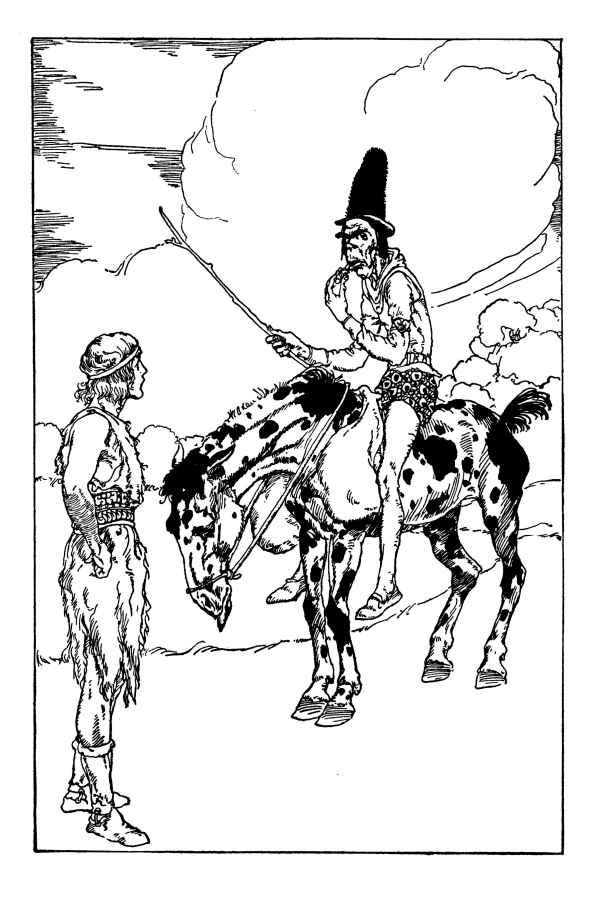

He rode on a bob-tailed, big-headed, spavined and spotted horse.

"And is there no way to get the better of him?" asked Gilly.

"There is, but it is a hard way," said the Spae-Woman. "If one could make him say that he, the master, is sorry for the bargain, the Churl himself would lose a strip of his skin an inch wide from his neck to his heel, and would have to pay full wages no matter how short a time the youth served him."

"It's a bargain anyway," said Gilly, "and if he comes I'll take service with the Churl of the Townland of Mischance."

The first wet day that came brought the Churl of the Townland of Mischance. He rode on a bob-tailed, big-headed, spavined and spotted horse. He carried an ash-plant in his hand to flog the horse and to strike at the dogs that crossed his way. He had blue lips, eyes looking crossways and eyebrows like a furze bush. He had a bag before him filled with boiled pigs' feet. Now when he rode up to the house, he had a pig's foot to his mouth and was eating. He got down off the bob-tailed, big-headed, spavined and spotted horse, and came in.

"I heard there was a young fellow at your house and I want him to take service with me," said he to the Spae-Woman.

"If the bargain is a good one I'll take service with you," said Gilly.

"All right, my lad," said the Churl. "Here is the bargain, and it's as fair as fair can be. I'll give you a guinea, a groat and a tester for your three months' work with me."

"I believe it's good wages," said Gilly.

"It is. Howsoever, if you ever say you are sorry you made the bargain you will lose your wages, and besides that you will lose a strip of your skin an inch wide from your neck to your heel. I have to put that in or I'd never get work done for me at all. The serving boys are always saying 'I can't do that,' and 'I'm sorry I made the bargain with you.' "

"And if you say you're sorry you made the bargain?"

"Oh, then I'll have to lose a strip of my skin an inch wide from my neck to my heel, and besides that I'll have to give you full wages no matter how short a time you served me."

"Well, if that suits you it will suit me," said Gilly of the Goatskin.

"Then walk beside my horse and we'll get back to the Townland of Mischance to-night," said the Churl. Then he swished his ash-plant towards Gilly and ordered him to get ready. The Spae-Woman wiped the tears from her face with her apron, gave Gilly a cake with her blessing, and he started off with the Churl for the Townland of Mischance.

W

HAT

did Gilly of the Goatskin do in the Townland of Mischance? He got up early and went to bed late; he was kept digging, delving and ditching until he was so tired that he could go to sleep in a furze bush; he ate a breakfast that left him hungry five hours before dinner-time, and he ate a dinner that made it seem long until supper-time. If he complained the Churl would say, "Well, then you are sorry for your bargain," and Gilly would say "No," rather than lose the wages he had earned and a strip of his skin into the bargain.

One day the Churl said to him, "Go into the town for salt for my supper, take the short way across the pasture-field, and be sure not to let the grass grow under your feet." "All right, master," said Gilly. "Maybe you would bring me my coat out of the house so that I needn't make two journeys." The Churl went into the house for Gilly's coat. When he came back he found Gilly standing in the nice grass of the pasture-field lighting a wisp of hay. "What are you doing that for?" said the Churl to him. "To burn the grass on the pasture-field," said Gilly. "To burn the grass on my pasture-field, you villain—the grass that is for my good race-horse's feeding! What do you mean, at all?" "Sure, you told me not to let the grass grow under my feet," said Gilly. "Doesn't the world know that the grass is growing every minute, and how will I prevent it from growing under my feet if I don't burn it?" With that he stooped down to put the lighted hay to the grass of the pasture-field. "Stop, stop," said the Churl, "I meant that you were to go to the town, without loitering on the way." "Well, it's a pity you didn't speak more clearly," said Gilly, "for now the grass is a-fire." The Churl had to stamp on the grass to put the fire out. He burnt his shins, and that made him very angry. "O you fool," said he to Gilly, "I'm sorry—" "Are you sorry for the bargain you made with me, Master?" "No. I was going to say I was sorry I hadn't made my meaning clear to you. Go now to the town and bring me back salt for my supper as quickly as you can."

After that the Churl was very careful when he gave Gilly an order to speak to him very exactly. This became a great trouble to him, for the people in the Townland of Mischance used always to say, "Don't let the grass grow under your feet," when they meant "Make haste," and "Don't be there until you're back," when they meant "Go quickly" and "Come with horses' legs" when they meant "Come with great speed." He became tired of speaking to Gilly by the letter, so he made up his mind to give him an order that could not be carried out, so that he might have a chance of sending him away without the wages he had earned.

One Monday morning he called Gilly to the door of the house and said to him, "Take this sheep-skin to the market and bring me back the price of it and the skin." "Very well, Master," said Gilly. He put the skin across his arm and went towards the town. The people on the road said to him, "What do you want for the sheep-skin, young fellow?" "I want the skin and the price of it," Gilly said. The people laughed at him and said, "You're going to give yourself a long journey, young fellow."

He went through the market asking for the skin and the price of it. Everyone joked about him. He went into the market-house and came to a woman who was buying things that no one else would buy. "What do you want, youth?" said she. "The price of the skin and the skin itself," said Gilly. She took the skin from him and plucked the wool out of it. She put the wool in her bag and put the skin back on the board. "There's the skin," said she, "and here's the price of it." She left three groats and a tester on top of the skin.

The Churl had finished his supper when Gilly came into the house. "Well, Master, I've come back to you," said Gilly. "Did you bring me the price of it and the skin itself?" said the Churl. "There is the skin," said Gilly, putting on the table the sheep-skin with the wool plucked out of it. "And here's the price of it—three groats and a tester," said he, leaving the money on top of the skin.

After that the Churl of the Townland of Mischance began to be afraid that Gilly of the Goatskin would be too wise for him, and would get away at the end of the three months with his wages, a guinea, a groat and a tester, in his fist. This thought made the Churl very downcast, because, for many months now, he had got hard labor out of his serving-boys, without giving them a single cross for wages.

T

HE

day after Christmas the Churl said to Gilly, "This is Saint Stephen's Day. I'm going to such a man's barn to see the mummers perform a play. Foolish people give these idle fellows money for playing, but I won't do any such thing as that. I'll see something of what they are doing, drink a few glasses and get away before they start collecting money from the people that are watching them. They call this collection their dues, no less."

"And what can I do for you, Master?" said Gilly.

"Run into the barn at midnight and shout out, 'Master, Master, your mill is on fire.' That will give me an excuse for running out. Do you understand now what I want you to do?"

"I understand, Master."

The Churl put on his coat and took his stick in his hand. "Mind what I've said to you," said he. "Don't be a minute later than midnight. Be sure to come in with a great rush—come in with horse's legs—do you understand me?"

"I understand you, Master," said Gilly.

The mummers were dancing before they began the play when the Churl came into the barn. "That's a rich man," said one of them to another. "We must see that he puts a good handful into our bag." The Churl sat on the bench with the farmer who had a score of cows, with the blacksmith who shod the King's horses, and with the merchant who had been in foreign parts and who wore big silver rings in his ears. Half the people who were there I could not tell you, but there were there—

Biddie Early

Tatter-Jack Walsh

Aunt Jug

Lundy Foot

Matt the Thresher

Nora Criona

Conan Maol, and

Shaun the Omadhaun.

Some said that the King of Ireland's Son was there too. The play was

"The Unicorn from the Stars."

The mummers did it very well although they had no one to take the part of the Unicorn.

They were in the middle of the play when Gilly of the Goatskin rushed into the barn. "Master, master," he shouted, "your mill—your mill is on fire." The Churl stood up, and then put his glass to his head and drained what was in it. "Make way for me, good people," said he. "Let me out of this, good people." Some people near the door began to talk of what Gilly held in his hands. "What have you there, my servant?" said the Churl. "A pair of horse's legs, Master. I could only carry two of them."

The Churl caught Gilly by the throat. "A pair of horse's legs," said he. "Where did you get a pair of horse's legs?"

"Off a horse," said Gilly. "I had trouble in cutting them off. Bad cess to you for telling me to come here with horse's legs."

"And whose horse did you cut the legs off?"

"Your own, Master. You wouldn't have liked me to cut the legs off any other person's horse. And I thought your race-horse's legs would be the most suitable to cut off."

The mummers and the people were gathered round them and they saw the Churl's face get black with vexation.

"O my misfortune, that ever I met with you," said the Churl.

"Are you sorry for your bargain, Master?" said Gilly.

"Sorry—I'll be sorry every day and night of my life for it," said the Churl.

"You hear what my Master says, good people," said Gilly.

"Aye, sure. He says he's sorry for the bargain he made with you," said some of the people.

"Then," said Gilly, "strip him and put him across the bench until I cut a strip of his skin an inch wide from his neck to his heel."

N

ONE

of the people would consent to do that. "Well, I'll tell you something that will make you consent," said Gilly. "This man made two poor servant-boys work for him, paid them no wages, and took a strip of their skin, so that they are sick and sore to this day. Will that make you strip him and put him across the bench?"

"No," said some of the people.

"He ordered me to come here to-night and to shout 'Master, master, your mill is on fire,' so that he might be able to leave without paying the mummers their dues. His mill is not on fire at all."

"Strip him," said the first mummer.

"Put him across the bench," said another.

"Here's a skinner's knife for you," said a third.

The mummers seized the Churl, stripped him and put him across the bench. Gilly took the knife and began to sharpen it on the ground.

"Have mercy on me," said the Churl.

"You did not have mercy on the other two poor servant-boys," said Gilly.

"I'll give you your wages in full."

"That's not enough."

"I'll give you double wages to give to the other servant-boys."

"And will you pay the mummers' dues for all the people here?"

"No, no, no. I can't do that."

"Stretch out your neck then until I mark the place where I shall begin to cut the skin."

"Don't put the knife to me. I'll pay the dues for all," said the Churl.

"You heard what he said," said Gilly to the people. "He will pay me wages in full, give me double wages to hand to the servant-boys he has injured, and pay the mummers' dues for everyone."

"We heard him say that," said the people.

"Stand up and dress yourself," said Gilly to the Churl. "What do I want with a strip of your skin? But I hope all here will go home with you and stand in your house until you have paid all the money that's claimed from you."