The Knight in History (14 page)

Read The Knight in History Online

Authors: Frances Gies

Each of the arms that the knight bore carried symbolic meaning. The shield protected him as he must protect the Holy Church from all malefactors, whether robber or infidel. As the hauberk guarded his body, he must defend the Church. As the helmet shielded his head, he must shield the Church from all who wished to injure her. The two edges of his sword signified that the knight was the servant of both Our Lord and of his people. The point signified the obedience the people owed the knight. The horse also symbolized the people, who must support him; the knight guarded them night and day, and therefore the people must provide him with the necessities of life. As the knight guided his horse, he must guide the people.

He must defend and maintain the church, and widows and orphans. “Knights must have two hearts, one as hard as a diamond, the other as soft and pliant as warm wax.” The hard heart must be inexorable toward traitors and felons, the soft heart merciful toward those who claimed pity.

Such were the requirements of knighthood, and those who could not fulfill them did well not to seek that estate, since they ran the danger of being disgraced here in this world and afterward with the Lord God.

Did any man exist who possessed all these virtues? Lancelot asked. Yes indeed, said the Lady of the Lake, even before Christ, and she listed the “very good knights” John the Hircanian, Judas Maccabeus and his brother Simon, King David, and after Christ’s passion “Joseph of Arimathea and his son King Galahad and their descendants.”

67

Chrétien’s

Perceval

was again unmistakably echoed in a late twelfth-century didactic poem,

L’Ordene de chevalerie (The Order of Chivalry)

, in which a Frankish knight explains to Saladin the rules and ceremonies of knighthood.

68

A hundred years later, the most famous and influential statement of the chivalric code, the

Libre del orde de cauayleria (Book of the Order of Chivalry)

by Spanish poet and theologian Raymond Lull, borrowed freely from the

Ordene

and from the Lady of the Lake’s advice in the Vulgate

Lancelot

. Widely circulated in Latin and French, it was translated into English and printed by William Caxton in 1484.

69

Through all these forms, adaptations, reiterations, and interpretations, the Arthurian romances made a deep impression on the knightly class that was their unvarying protagonist. Elements of the romances were acted out in courts and castles. Beginning in the thirteenth century, and growing more elaborate as time progressed, in England, France, Flanders, and the Holy Land “Round Tables” were organized—feasts and tournaments in imitation of those at Camelot. Sometimes participants took the names of Arthur, Lancelot, Galahad, Gawain, Yvain, or Perceval. In 1344 Edward III founded in imitation of King Arthur the order of knights that became the Order of the Garter.

70

To whatever degree the knight of the High Middle Ages consciously tried to be faithful to the courtly image of the troubadours and the heroic examples of the

chansons de geste

, while modeling himself after Lancelot and Perceval and heeding the injunctions of the Lady of the Lake, these powerful images and standards could not fail to influence his self-perception. The knight of the twelfth and thirteenth century was, above all in his own eyes, measurably above the crude, uncivilized warrior of the tenth century.

William Marshal: Knighthood at its Zenith

MANY NOBLE MEN BY THEIR INDOLENCE

LOSE GREAT GLORY, WHICH THEY COULD HAVE

IF THEY ROVED THROUGH THE WORLD

.

NOT CONSONANT WITH EACH OTHER

ARE IDLENESS AND GLORY, I THINK

,

FOR NO GLORY IS WON

BY THE RICH MAN, WHO IDLES EVERY DAY

.

—Chrétien de Troyes,

Cligès

THEY SOJOURNED IN ENGLAND

ALMOST A YEAR, IN WHICH HE DID NOTHING

BUT ENGAGE IN JOUSTS

OR IN THE HUNT OR THE TOURNEY

.

BUT TO THE YOUNG KING IT WAS NOT PLEASING

,

HIS COMPANIONS ALSO

WERE TERRIBLY BORED

,

FOR THEY PREFERRED TO ROAM RATHER

THAN TO SOJOURN, IF THEY COULD WANDER

.

FOR KNOW WELL, IT IS THE GIST

,

THAT A LONG SOJOURN DISHONORS A YOUNG MAN

.

—L’Histoire de Guillaume Maréchal

T

HE ROMANCES of adventure and the Arthurian romances centered around the exploits of fictional knights-errant. Through the accident of history we possess the biography of a real knight-errant, William Marshal, a unique document that owes its existence to the fact that its knight hero rose to become a great baron and played a powerful political role. Shortly after his death his eldest son employed William’s squire, John d’Erley, to write, with the aid of a trouvère whose name is unknown,

The History of William Marshal (L’Histoire de Guillaume Maréchal)

.

1

Composed in the form of a verse romance, the biography is in French, the language of the twelfth-century English court and literature. Though the work was designed to glorify its subject, and therefore embroiders his role, the authors were contemporaries and sometimes eyewitnesses of the events they record

*

and the biography was aimed at a knowledgeable contemporary audience. Many of the facts are externally verifiable. Its picture of society may be romanticized, but it nevertheless reveals much about the manners, customs, and values of the knightly class of the twelfth century.

William Marshal was the son and grandson of court officials of King Henry I of England. His grandfather Gilbert, a small Wiltshire landholder, the first member of the family about whom anything is known, became royal marshal, in charge of the king’s horses. Gilbert and his son John, William’s father, successfully defended by judicial duel (trial by combat) their right to the office of marshal and its hereditary status. Taking the term “Marshal” first as a title and later as a surname, John married a member of his own middling social class, the heiress of another small Wiltshire landholder, and by her had his first two sons, Gilbert and Walter.

2

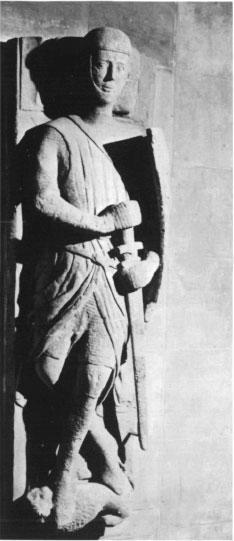

EFFIGY ON WILLIAM MARSHAL’S TOMB IN THE TEMPLE CHURCH, LONDON.

(DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT)

Until the death of Henry I in 1135, and for the first years of the reign of King Stephen, John Marshal remained a minor official and petty landholder, neither wealthy nor powerful. But when Henry I’s daughter Matilda (once empress of Germany, now countess of Anjou) invaded England in 1139 to challenge Stephen’s rule, John seized the opportunity the civil war offered. Shrewd, ruthless, and able, he first sided with Stephen, seizing castles in the king’s name and holding them for his own benefit. When Matilda began to gain the upper hand, he switched loyalties, managing at the same time to get rid of his first wife by annulment and to make a more advantageous marriage with Sibile, sister of the future earl of Salisbury. This marriage produced four sons and two daughters. The second son, born about 1144, was William.

*

3

Of William’s early childhood the

History

narrates a single picturesque incident. Besieging Newbury Castle in 1152, King Stephen granted its commandant a truce to confer with John. John asked for a further truce while he petitioned Countess Matilda for aid. The king agreed, but required the surrender of one of John’s sons as hostage. William, the youngest, was chosen. When John used the respite to provision and garrison the castle, Stephen threatened to hang the young hostage unless John surrendered. John defied him, sending word that he “had the anvils and hammers with which to forge still finer sons.” The boy was led out to be hanged, but his innocent confidence so touched the king’s heart that he picked him up and carried him back to camp.

4

Later someone proposed that they catapult William over the castle wall, but good-hearted Stephen forbade it, saying, “William, you will never be harmed by me.”

5

William spent two months as prisoner of the king at Newbury. His mother sent a servant to spy. Peering into the king’s tent, the man saw William and the king playing “knights” with plantain weeds. As the servant watched, the boy struck off the clump of leaves that represented the head of his opponent’s knight. Catching sight of his mother’s servant, he greeted him with a shout: “Welcome, Wilikin! How is my lady mother? How are my sisters and brothers?” The terrified servant fled and narrowly escaped.

6

The civil war ended in 1153 with a treaty by which Stephen was to rule for the rest of his life and be succeeded by Matilda’s son, Henry Plantagenet, count of Anjou. Stephen died the following year, and Henry became king as Henry II. Young William was returned to his parents and John Marshal was rewarded for his services to Matilda with life revenues from valuable manors in Wiltshire. With these, plus estates he had inherited from his father and other scattered lands, he had substantially improved his economic situation over that of his father, but he was still not in a position to provide for his sons. By primogeniture, the eldest, Gilbert, would inherit the office of marshal and John’s lands; the others would have to fend for themselves.

7

In 1156 William was sent to Normandy to be educated as a knight in the castle of a powerful cousin, William of Tancarville, chamberlain to the duke of Normandy.

8

The

History

records that twelve-year-old William wept on saying goodbye to his mother and sisters and brothers, like any adolescent off to school for the first time, then rode away, accompanied by two servants.

9

William’s apprenticeship as a squire involved training with lance and sword, caring for his master’s weapons and armor, looking after his horses, helping him dress, waiting on him at table, and carving his meat. From the songs and romances sung in the castle hall he absorbed the ideology of knighthood.

At the age of twenty, in about 1164, William was knighted. The ceremony took place during an episode in the war between Henry II of England and Louis VII of France, when Henry called on William of Tancarville to assist his ally, Count John of Eu.

*

Meeting Count John and William de Mandeville, earl of Essex, at Drincourt (now Neufchatel-en-Bray), northeast of Rouen, the lord of Tancarville decided to knight William in anticipation of the battle.

10

The dubbing ritual had by this time undergone complete Christianization, with the ancient blessing of the sword expanded to a religious investment of every element of the ceremony. As described in

L’Ordene de chevalerie

, nearly contemporary with William Marshal, the candidate first was bathed, the bath symbolizing the washing away of his sins. Then he was clothed in a white robe symbolizing his determination to defend God’s law, with a narrow belt to remind him to shun the sins of the flesh. In the church, he was invested with his accoutrements: the gilded spur, to give him courage to serve God; the sword, to fight the enemy and “protect the poor people from the rich.” Finally, he received the

colée

, a blow of the hand on the shoulder or head, “in remembrance of Him who ordained you and dubbed you knight.”

11