The Knight in History (23 page)

Read The Knight in History Online

Authors: Frances Gies

The Teutonic Knights, never important in Asia Minor, played a historic role in northeast Europe, where they conducted “Crusades” against the pagan natives of Livonia (modern Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia) and founded the state of Prussia. The Order reached the height of its power in the fourteenth century but declined rapidly following its defeat by Polish and Lithuanian forces at the battle of Grünwald in 1410. Its last branch was dissolved by Napoleon in 1809. In 1834 both Hospitalers and Teutonic Knights were revived: the Hospitalers by the establishment of a headquarters in Rome, where they remain to this day, a medieval relic with members around the world; the Knights converted into an honorary ecclesiastical institution with headquarters in Vienna.

For European knighthood, however, the real legacy of the Military Orders was not their anticlimactic later history but the conspicuous model they furnished of the Christian warrior, the knight who served God through the profession of arms.

Bertrand du Guesclin: a Knight of the Fourteenth Century

REGNAULT DU GUESCLIN WAS THE CHILD’S FATHER, HIS MOTHER WAS A GENTLE LADY AND VERY FAIR. BUT AS FOR THEIR CHILD, I MUST TELL YOU THERE WAS NONE UGLIER BETWEEN RENNES AND DINANT

.

—Jean Cuvelier,

Chronique de Bertrand du Guesclin

“SIR BERTRAND,” SAID THE KING, “I HAVE NEITHER BROTHER, NOR COUSIN, NOR NEPHEW, NOR COUNT, NOR BARON IN MY KINGDOM WHO WOULD REFUSE TO OBEY YOU. IF ANY DID, HE WOULD KNOW MY ANGER

.”

—Froissart,

Chroniques

“IF THE KING WANTS TO MAKE ME CONSTABLE, HE MUST PAY HIS SOLDIERS TO MAINTAIN THEM…FOR SOLDIERS WANT THEIR PAY. IF THEY AREN’T WELL PAID, THEY WON’T SERVE, AND IF THEY GO UNPAID THEY’LL PILLAGE

.”

—Du Guesclin, quoted by Cuvelier

B

ERTRAND D

U

GUESCLIN (pronounced Gecklin), the most famous knight of the fourteenth century, was born in Brittany in about 1320 and died July 13, 1380, while besieging a castle in Gascony.

1

In between he fought in a half-dozen large battles, in dozens of smaller battles, and in hundreds of sieges, in addition to uncounted and nameless skirmishes, raids, sorties, surprises, and ambushes. Besides the thousands of blows dealt and received in these with sword, axe, mace, and lance, he fought many duels and took part in numerous tournaments. By the time of his death at sixty, his body was covered with scars. Taken prisoner four times, he witnessed and indeed encouraged the rise in the price of his ransom to the princely figure of 100,000 gold florins. In his turn he profited from the ransoms of hundreds of noble and knightly captives and exacted levies from innumerable captured castles, towns, and cities, but, caring nothing for wealth, he died nearly as poor as when he was born. A popular hero of legendary proportions, he was accorded the lion’s share of the credit for the reversal of the tide of the Hundred Years War that took place under Charles V in the 1360s and 1370s.

2

No great general in the modern sense, but a consummate leader, he owed his success to his reckless bravery, physical hardihood, and talent as a

guerroyeur

, a planner and manager of operations on the petty scale on which nine tenths of the warfare of his day was conducted.

In addition to his valor and skill, Du Guesclin was universally credited by his contemporaries with a recommended but rare knightly virtue, a solicitude for the poor and helpless. Nineteenth-century historians, regarding patriotism as a virtue necessary to a hero, credited him with contributing to the birth of national sentiment, though he himself claimed only the medieval and knightly virtue of loyalty.

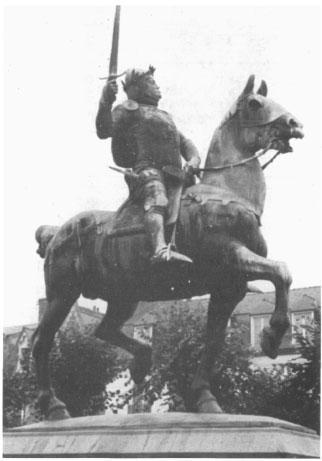

STATUE OF BERTRAND DU GUESCLIN, DINAN, BRITTANY

.

As in the case of William Marshal, we owe information on Du Guesclin’s personal life to the fact that he became famous. In addition to the

Chronicles

of Froissart, he figures prominently in the

Cronica del rey don Pedro

of Lopez de Ayala, an eyewitness to much of Du Guesclin’s Spanish adventure, and in several other histories and chronicles of the era. But the sole source of information about his birth, boyhood, and youth, and about numerous details of his mature life, is the

Chronique de Bertrand du Guesclin

, by a Picard trouvère named Jean Cuvelier. A long (22,790 lines) poem, Cuvelier’s work exhibits the colorfully unreliable character of an epic, yet its proximity in time—written within a year of its hero’s death—gives it considerable credibility, supported by the agreement of other sources on many facts. Its popularity may lend added credence, since many of Du Guesclin’s companions-in-arms, including the royal princes who served with and under him, owned copies, that of the duke of Burgundy reputed worn by much perusal. Nothing is known of Cuvelier himself or his sources, which may have included a lost journal kept by Du Guesclin’s herald-at-arms. Like Froissart and chroniclers going back to Herodotus, Cuvelier freely reports speeches and dialogues that perhaps show only what the writer and his readers regarded as appropriate.

There is no reason to doubt Cuvelier’s statement that Bertrand was born the oldest child of the large family of Regnault du Guesclin, a knight of modest fortune, in La Motte, near Dinan, Brittany.

3

Regnault was a younger son of a family whose elder branch held extensive lands on the little peninsula on which St. Malo stands. His fief of La Motte-Broons was only slightly augmented by the dowry of his wife, Jeanne Malemains, consisting of a piece of land and a mill. Jeanne was credited with bringing to the marriage beauty rather than wealth, which perhaps drew the more attention to a conspicuous lack of beauty on the part of her firstborn, who was named for his godfather, Bertrand de Saint-Perm, a knightly friend of the family. According to Cuvelier, the boy’s mother was so repelled by his looks that she treated him with a coldness that provoked resentment expressed in savage outbursts against parents, siblings, and the world. What is well established by other sources is that as a grown man Du Guesclin was the reverse of handsome, and, at least in his younger manhood, subject to fits of furious anger.

4

There is no indication, however, that he retained any lasting resentment against his mother.

Perhaps his status as first child in a large family inclined him to leadership. He organized the boys of the neighborhood in tournaments in imitation of adult sport, much as a youthful leader of a later age might organize football games. Bertrand always commanded one party in the melee, but when his side appeared to be winning too easily he switched to the other. The battle ended on his command, whereupon (says Cuvelier) he led the way to a local inn and stood treat. To pay for this extravagance he is said to have sold a horse of his father’s, which led to a ban on his tournaments, doubly enforced by Regnault’s order to his peasants to keep their sons from associating with Bertrand, and by locking Bertrand in his room. But the Du Guesclin manor house was hardly a donjon and one day Bertrand, who was fifteen or sixteen, seized the keys from the woman servant who brought him his food, locked her up in his place, commandeered a farm horse from a peasant, and rode thirty kilometers without saddle or bridle to Rennes, where he had an aunt and uncle. The aunt was shocked but the uncle indulgent and he was allowed to stay.

5

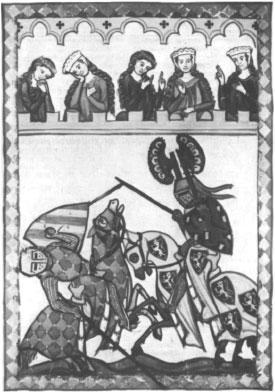

FOURTEENTH-CENTURY TOURNAMENT INVOLVED INDIVIDUAL COMBAT IN THE “LISTS.” KNIGHTS WORE IDENTIFYING CRESTS, AS WELL AS ARMORIAL BEARINGS ON SURCOATS, SHIELDS, AND HORSES’ COVERINGS.

(MANESSE CODEX, UNIVERSITÄ TSBIBLIOTHEK HEIDELBERG, MS. PAL. GERM. 848, F. 250)

Bertrand is described at this stage as of middle height (probably not much over five feet), with swarthy complexion, a flat nose, gray eyes, broad shoulders, long arms, and small hands.

6

One Sunday he accompanied his aunt to church but slipped away to join in a combat organized by the town youth of Rennes. He succeeded in overthrowing a young champion who had hurled a dozen others to earth, but injured his knee on a sharp stone and had to be helped home. His aunt reproached him, partly for fighting, more for fighting with lower-class boys, and extracted a promise to fight henceforth only in noble tournaments.

Time brought reconciliation with his father, and shortly afterward an opportunity to fulfill his promise to his aunt. The marriage of the duke of Brittany’s niece to a nephew of the king was the occasion for a celebratory tournament in Rennes to which Bertrand’s father repaired with the family’s best horse. Bertrand took a nag from the stable, followed, and met with luck. Tournaments had undergone refinement since William Marshal’s time, with the action limited to a single field, the “lists,” and a fixed number of courses, or charges, assigned to each cavalier. A cousin of Bertrand’s had completed his courses and was willing to lend horse and armor. Galloping into the lists, Bertrand unhorsed several combatants without revealing his identity. The only champion to rival him was his father, with whom he avoided combat. His helmet got knocked off by another adversary and the elder Du Guesclin, recovering from his astonishment, promised to treat him properly in the future, in other words, to provide him with suitable horse and armor.

7

Armor was in the mid-fourteenth century slowly but definitely evolving from mail to plate. Breastplates were occasionally worn under or over the hauberk in the thirteenth century and perhaps earlier; by Du Guesclin’s time the practice was common. In the earlier period the breastplate was typically of

cuir bouilli

, leather hardened by boiling with wax, whence the name cuirass, but by now it was nearly always of iron. More widely used, however, was the “coat of plates,” a garment of leather or fabric armored with vertical rectangular iron plates, at first nearly knee length, later shortened. Reinforcing plates were also widely worn, on elbows, knees, and at the throat, and were becoming popular for thighs, shins, arms, and shoulders as the advantage of smooth plate in warding off glancing blows of point or blade became recognized.

8

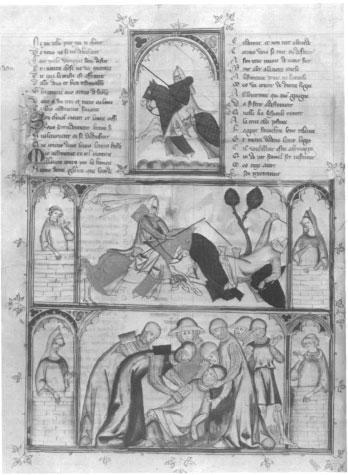

FOURTEENTH-CENTURY TOURNAMENT:

CENTER

, BREAKING A LANCE;

BELOW

, SUCCORING THE WOUNDED.

(BIBLIOTHÈQUE NATIONALE, MS. FR. 146, F. 40V)

Arming either for tournament or battle, a well-equipped knight of the 1340s would have first donned a close-fitting shirt, short breeches, and hose. Over these would go mail leggings, heavy quilted thigh protectors (gamboised cuisses) with knee plates attached, greaves for the shins, and iron shoes (sabatons). Next he put on the heavy fabric acton, over which went his hauberk with shoulder and elbow plates attached, and his coat of plates. The surcoat went over everything. A narrow belt circled the waist; the broader sword belt hung more loosely around the hips. Gauntlets of iron plates riveted to layers of fabric, tinned or coppered against rusting, were drawn over the hands. A new rounded or conical helmet (basinet) had a visor to protect the face. Its crown was lined with leather pulled together at the top by a cord; when it was placed on his head, the knight was ready for combat. The shield had diminished in size, becoming a downward-pointing triangle with curved sides, but it was still considered indispensable.

9