The Korean War (27 page)

The men of Eighth Army exulted in their triumphal drive north, the road race towards the Yalu. The British were astonished to see a senior officer of 1st Cavalry Division riding his jeep past their column, seated astride a massive cowboy saddle. Amid negligible resistance, the chief peril lay in carelessness about the position of the enemy. On 17 October, the Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders were approaching the industrial town of Sariwon. They had

expected it to be strongly defended, but found instead only bombed and burning buildings. The supporting tanks opened fire with their machine guns on a distant group of enemy who appeared on the skyline, but otherwise the town appeared abandoned. The colonel was conducting an Orders Group in its midst, his officers gathered among their cluster of vehicles, when they saw a large truck laden with men tearing towards them. Suddenly, they perceived that it was North Korean. There was a long moment’s silence. Then a fierce gun-battle began, terminated by a grenade thrown into the truck by an Argyll. Peace restored, young Lieutenant Colin Mitchell was sent off westwards in a bren carrier, to reconnoitre a new base. His party drove cheerfully down a long column of Korean infantry – North Korean. One officer fired a pistol at them. The remainder of those beaten men had no stomach for combat: ‘Some looked up at us. Others just plodded on. After four miles of this inspection of the enemy, we had reached their rear echelons and baggage trains, and were gratified that they moved their bullock carts out of our paths as we kept going.’

5

Once clear of the enemy, prudence once more overtook the British party. They hid in a ditch through the night.

As Eighth Army’s drive north continued, MacArthur made plain his contempt for the carefully drawn niceties of Washington and the UN, about restricting movement near the Chinese border to South Korean forces. He responded witheringly when he heard of a British proposal for the establishment of a buffer zone south of the Yalu, jointly policed by China and the UN:

The widely reported British desire to appease the Chinese communists by giving them a strip of North Korea finds its historic precedent in the action taken at Munich on 29 September 1938 . . . To give up any portion of North Korea to the aggression of the Chinese communists would be the greatest defeat of the free world in recent times. Indeed, to yield to so immoral a proposition would bankrupt our leadership and influence in Asia, and render untenable our position both politically and morally.

6

When he issued orders, on 20 October, for ‘all concerned’ within his command to prepare for a ‘maximum effort’ to advance rapidly to the border of North Korea, the Joint Chiefs made no attempt to interfere. Fear of Chinese intervention had sunk so low that on 23 October, at a joint meeting in Washington of the British and American Chiefs of Staff, Bradley declared soothingly: ‘We all agree that, if the Chinese communists come into Korea, we get out.’ On 24 October, MacArthur’s new directive removed all remaining restrictions on the movement of American troops towards the Yalu. Walker and Almond were ‘authorized to use any and all ground forces as necessary, to secure all of North Korea’. The Joint Chiefs in Washington queried this order, which was ‘a matter of some concern here’. MacArthur brushed them aside. General Collins and his colleagues were in no doubt that they were being flatly disobeyed by the commander in the field. In the same week, they requested MacArthur to issue a statement, setting at rest fears in the UN Security Council that the Chinese might move across the Yalu to protect their vital Suiho electrical generating plant, unless this was declared safe from UN military action. MacArthur declined to give such an assurance, unless he was sure the plant was not powering communist munitions production. Yet again, with the war almost over, the Joint Chiefs showed their unwillingness to precipitate a confrontation. Washington resigned itself to playing the hand against the communists MacArthur’s way.

‘We are going to go ahead and force the issue now,’ a Department of State spokesman told a correspondent in Washington.

7

The decision to advance north across the 38th Parallel was a classic example of military opportunity becoming the engine of action, at the expense of political desirability. No rigorous debate was carried to a conclusion about UN, or US, objectives in occupying the North.

The very great political and diplomatic hazards were submerged by the public perception of the prospect of outright military victory. At the root of American action lay a contempt, conscious or unconscious, for the capabilities of Mao Tse Tung’s nation and armed forces. The Chinese communists were considered a sinister ideological force in Asia, but not a formidable military one. Far greater courage and determination would have been required from the Truman Administration for a decision to halt Eighth Army at the 38th Parallel than was demanded for acquiescence in MacArthur’s drive to victory. If there remained a measure of apprehension within the Administration about entering North Korea, there was also the powerful scent of triumphalism among many prominent Americans. Harold Stassen declared in a speech in support of Republican candidates on 5 November that the war in Korea was ‘the direct result of five years of building up Chinese communist strength through the blinded, blundering American-Asiatic policy of the present national administration . . . five years of coddling Chinese communists, five years of undermining General MacArthur, five years of appeasing the arch-communist, Mao Tse Tung’. Now Mao was to be appeased no longer. American arms were being carried to the very frontier of his vast land.

7 » THE COMING OF THE CHINESE

On the evening of 1 November 1950, Private Carl Simon of G Company, 8th Cavalry, lay in the company position with his comrades, speculating nervously about the fate of a patrol of F Company, which had reported itself in trouble, ‘under attack by unidentified troops’. As the darkness closed in, they heard firing, bugles, and shouting. Their accompanying Koreans could not identify the language, but said that it must be Chinese. When a wave of yelling enemy charged the Americans out of the gloom, firing and grenading as they came, no effective resistance was offered. ‘There was just mass hysteria on the position,’ said Simon. ‘It was every man for himself. The shooting was terrific, there were Chinese shouting everywhere, I didn’t know which way to go. In the end, I just ran with the crowd. We just ran and ran until the bugles grew fainter.’

1

The war diaries of 1st Cavalry Division, of which 8th Cavalry was a part, present the events at Ansung in a somewhat more coherent, less armageddonist spirit than PFC Simon. But since his uncomplicated perception – of a thunderbolt from the night that brought the entire ordered pattern of his army life down about his head – was to become common to thousands of other young Americans in Korea in the weeks that followed, it seems no less valid than that of his superiors.

The twenty-year-old New York baker’s son had joined the army to see the world. He was in transit to Japan when the war began, and had to look on a map to discover where Korea was. When he saw the place for himself, he liked it not at all. His unit had been uneasy, unhappy and uncomfortable since it crossed the 38th Parallel. Simon himself had been slightly wounded in a skirmish

soon after entering North Korea. The only moment of the war he had enjoyed was the Bob Hope Show in Pyongyang, though he was so short that he had to keep jumping up and down among the vast audience of soldiers, to catch a glimpse of the distant stage. Simon was one of many thousands of men vastly relieved to find the war almost over, impatient to get home.

Yet now, he found himself among thirty-five frightened fugitives, in the midst of Korea without a compass. The officers among them showed no urge to exercise any leadership. The group merely began to shuffle southwards. Most threw away their weapons. They walked for fourteen days, eating berries, waving their yellow scarves desperately but vainly to observation planes. Once, in a village, they got rice and potatoes at gunpoint from a papa-san. At night, they gazed at the curious beauty of the hills, on fire from strafing. For a time, they lay up in the house of a frightened civilian, who eventually drove them out with his warnings of communists in the area. They were close to physical collapse, and to surrender, when one morning they thought they glimpsed a tank bearing a ‘red carpet’ identification panel. They ran forward, and found on the ground a London newspaper. Then they saw British ration packs, and at last, far below them in the valley, a tracked vehicle moving. They determined to make for it, whatever the nationality of its occupants. To their overwhelming relief, they found themselves in the hands of the British 27 Brigade.

PFC Simon and his companions were a small part of the flotsam from the disaster that befell the US 1st Cavalry Division between 1 and 3 November, which also inflicted desperate damage upon the ROK II Corps. The South Koreans were the first to be heavily attacked. The Chinese 116th Division struck against the 15th ROK. Then, on 1 November near Ansung, about midway across the Korean peninsula, it was the turn of the Americans. Strong forces hit them with great determination, separating their units, then attacking them piecemeal. Batteries in transit on the roads, rifle

companies on positions, found themselves under devastating fire from small arms, mortars and katyusha rockets. The 3rd Battalion of the 8th Cavalry was effectively destroyed. The regiment’s other battalions were severely mauled, and elements of the 5th Cavalry damaged. Yet when the 1st Cavalry Division’s action ended, activity across the Korean battle front once again dwindled into local skirmishes.

Herein lies one of the greatest, most persistent enigmas of the Korean War. More than three weeks before the main Chinese onslaught was delivered with full force, Peking delivered a ferocious warning by fire: we are here, said the Chinese, in the unmistakable language of rifle and grenade, in the mountains of Korea that you cannot penetrate. We can strike at will against your forces, and they are ill-equipped in mind and body – above all, in mind – to meet us. We are willing to accept heavy casualties to achieve tactical success. The armies of Syngman Rhee are entirely incapable of resisting our assaults.

Yet this message, this warning, MacArthur and his subordinates absolutely declined to receive. They persisted in their conviction that their UN armies could drive with impunity to the Yalu. They continued to believe that the Chinese were either unwilling or unable to intervene effectively. They showed no signs of alarm at the evidence that not only the ROK divisions, but their own, were at something less than peak fighting efficiency. They had created a fantasy world for themselves, in which events would march in accordance with a divine providence directed from the Dai Ichi building. The conduct of the drive to the Yalu reflected a contempt for intelligence, for the cardinal principles of military prudence, seldom matched in twentieth-century warfare.

The first ROK forces reached the Yalu on 25 October, and sent back a bottle of its intoxicating waters to Syngman Rhee. Some soldiers, like their American counterparts, equally symbolically chose to urinate from its bank. On the same day, the ROK II Corps, driving

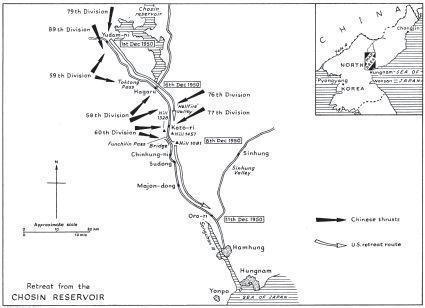

north on the western axis of the UN advance, was strongly attacked, and in the action that followed, almost destroyed. The ROKs reported that the agents of their disaster were Chinese, and sent some Chinese prisoners to the Americans. General Paek Sun Yup, probably the ablest South Korean commander, was at this time transferred to temporary command of II Corps, and demanded to see the PoWs personally at his Command Post. He himself spoke fluent Chinese, and immediately established that the prisoners were indeed from the mainland, with southern accents. They wore Chinese reversible smocks. Paek asked them: ‘Are there many of you here?’ They nodded. ‘Many many.’ Paek reported the conversation directly to I Corps’s commander, ‘Shrimp’ Milburn. But Milburn was no more impressed by the Korean than by his own intelligence officer, Colonel Percy Thomas, who was also convinced that there was now a serious Chinese threat. General Walker himself sought to explain away the presence of some Chinese among the North Koreans as insignificant: ‘After all, a lot of Mexicans live in Texas . . .’ II Corps fell back as the enemy advanced under cover of vast makeshift smokescreens, created by setting fire to the forests through which they marched. When the US 1st Cavalry passed through the ROKs to take up the attack, the division was savaged. Meanwhile in the east, the ROK 1st Corps moving north from Hamhung was stopped in its tracks on the road to the hydroelectric plants of the Chosin reservoir. As early as 25 October, the ROK 1st Division found itself heavily engaged, and captured a soldier who admitted that he was Chinese. The next day, more prisoners were taken, who were identified as members of the 124th Division of the Chinese 42nd Army. By 31 October, twenty-five Chinese prisoners had been taken, and the strength of the communist force at the foot of the Chosin reservoir was apparent.