The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn (2 page)

Read The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn Online

Authors: Alison Weir

Tags: #General, #Historical, #Royalty, #England, #Great Britain, #Autobiography, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Biography And Autobiography, #History, #Europe, #Historical - British, #Queen; consort of Henry VIII; King of England;, #Anne Boleyn;, #1507-1536, #Henry VIII; 1509-1547, #Queens, #Great Britain - History

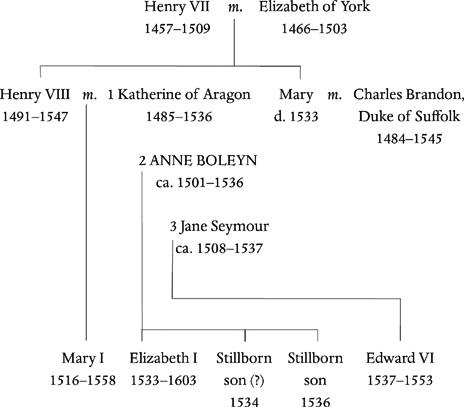

GENEALOGICAL TABLE 1

The Tudors

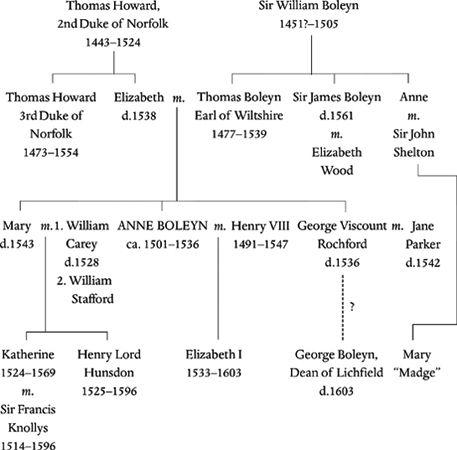

GENEALOGICAL TABLE 2

The Boleyns

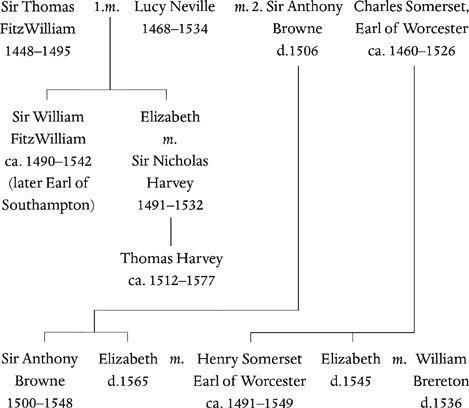

GENEALOGICAL TABLE 3

The

Fitz William Connections

PROLOGUE

The Solemn Joust

The Solemn JoustM

ay Day was one of the traditional highlights of the English royal court’s spring calendar, and was customarily celebrated as a high festival. The May Day of 1536 was no exception, being marked by a great tournament, or “solemn joust,” which was held in the tiltyard at Greenwich, the beautiful riverside palace much favored by King Henry VIII, who had been born there in 1491. It was a warm day, and pennants fluttered in the breeze as the courtiers crowded into their seats to watch the contest.

1

At the appointed time, the King took his place at the front of the royal stand, which stood between the twin towers of the tiltyard, in front of the recently built banquet hall. He was not yet the bloated and diseased colossus of his later years, but a muscular and vigorous man of forty-five, over six feet tall,

2

red-bearded and magnificently dressed: “a perfect model of manly beauty,” “his head imperial and bald.”

3

His queen of three years, Anne Boleyn, seated herself beside him. One of the most notorious women in Christendom, she was ten years younger than her husband, very graceful, very French—she had spent some years at the French court—and stylishly attired, but “not the handsomest woman in the world”: her skin was swarthy, her bosom “not much raised,” and she had a double nail on one of her fingers; her long brown

hair was her crowning glory, and her other claim to beauty was her eyes, which were “black and beautiful” and “invited to conversation.”

4

It was outwardly a happy occasion—May Day was traditionally the time for courtly revelry—and there was little sign of any gathering storm. Henry “made no show” of being angry or in turmoil, “and gave himself up to enjoyment.”

5

He watched as the contestants ran their chivalrous courses, lances couched, armor gleaming. At this “great jousting,” the Queen’s brother, George Boleyn, Viscount Rochford, was the leading challenger and “showed his skill in breaking lances and vaulting on horseback,” while Sir Henry Norris, one of the King’s most trusted friends and household officers, led the defenders, “presenting himself well-armed.” When Norris’s mount became uncontrollable, “refused the lists, and turned away as if conscious of the impending calamity to his master,” the King presented him with his own horse.

6

In the jousting, the poet-courtier Thomas Wyatt “did better than the others,” although Norris, Sir Francis Weston, and Sir William Brereton all “did great feats of arms, and the King showed them great kindness. The Queen looked on from a high place, and often conveyed sweet looks to encourage the combatants, who knew nothing of their danger.”

7

Fifty years later, Nicholas Sander, a hostile Catholic historian, would claim that “the Queen dropping her handkerchief, one of her gallants [traditionally assumed to have been Henry Norris] took it up and wiped his face with it,” and that Henry VIII, observing this and seething with jealousy, construed the gesture as evidence of intimacy between them, and rising “in a hurry,” left the stand; but there is no mention of this incident in contemporary sources such as the reliable chronicle of Charles Wriothesley, Windsor Herald. In the late seventeenth century, Gilbert Burnet, Bishop of Salisbury, who painstakingly researched Anne Boleyn’s fall in order to refute the claims of Sander, would conclude that the handkerchief incident never happened, since “this circumstance is not spoken of by [Sir John] Spelman, a judge of that time who wrote an account of the whole transaction with his own hand in his commonplace book.”

Halfway through the jousts a message was passed to Henry VIII, and suddenly, to everyone’s astonishment, especially the Queen’s, “the King departed to Westminster, having not above six persons with him,”

8

leaving Anne to preside alone over what remained of the tournament. “Of which sudden departing, many men mused, but most chiefly the Queen.”

9

She

must have felt bewildered and fearful at the very least, because for some days now, the King had been distant or simmering with rage, and she had very good reasons to suspect that something ominous had happened—and that it concerned herself.

She was the Queen of England, and she should have been in an invincible position, yet she was painfully aware that she had disappointed Henry in the most important thing that mattered. She could not have failed to realize that his long-cherished passion for her had died and that his amorous interest now had another focus, but she clearly also knew that there was more to this present situation than mere infidelity. For months now the court had been abuzz with speculation that the King might take another wife. But that was not all.

A week before the tournament, Anne’s brother—one of the most powerful men at court—had been publicly slighted. That could have been explained in a number of ways, but many saw it as a slur upon herself. Since then, her father, a member of the King’s Council and privy to state secrets, who could have told her much that would frighten her, may have said something that gave her cause for alarm. She had perhaps guessed that members of her household were being covertly and systematically questioned. How she found out is a matter for speculation, but there can be no doubt that she knew something was going on. Just four days earlier she had sought out her chaplain and begged him to look to the care of her daughter should anything happen to her, the Queen. Plainly, she was aware of some undefined, impending danger.

She knew too that, only yesterday, her tongue, never very guarded, had run away with her and that she had spoken rashly, even treasonously, overstepping the conventional bounds of courtly banter between queen and servant, man and woman, and also that her words had been overheard. She was fretting about that, and had gone so far as to take steps to protect her good name. But it was too late. Others were putting their own construction on what she had said, and it was damning.

Anne seems to have feared that the King had been told of her compromising words. On the day—or the morning—before the tournament, she had made a dramatic, emotional appeal to him, only to be angrily rebuffed. Then late that evening, come the startling announcement that a planned—and important—royal journey had been postponed.

The signs had not been good, but the exact nature of the forces that

menaced Anne was almost certainly a mystery to her. So she surely could not have predicted, when the King got up and walked out of the royal stand on that portentous May Day, it would be the last time she’d ever set eyes on him, and that she herself and those gallant contestants in the jousts were about to be annihilated in one of the most astonishing and brutal coups in English history.

Occurrences That Presaged Evil

Occurrences That Presaged EvilT

hree months earlier, on the morning of January 29, 1536,

1

in the Queen’s apartments at Greenwich Palace, Anne Boleyn, who was Henry VIII’s second wife, had aborted—“with much peril of her life”

2

—a stillborn fetus “that had the appearance of a male child of fifteen weeks growth.”

3

The Imperial ambassador, Eustache Chapuys, called it “an abortion which seemed to be a male child which she had not borne three-and-a-half months,”

4

while Sander refers to it as “a shapeless mass of flesh.” The infant must therefore have been conceived around October 17.

This was Anne’s fourth pregnancy, and the only living child she had so far produced was a girl, Elizabeth, born on September 7, 1533; the arrival of a daughter had been a cataclysmic disappointment, for at that time it was unthinkable that a woman might rule successfully, as Elizabeth later did, and the King had long been desperate for a son to succeed him on the throne. Such a blessing would also have been a sign from God that he had been right to put away his first wife and marry Anne. Now, to the King’s “great distress,”

5

that son had been born dead. It seemed an omen. She had, famously, “miscarried of her savior.”

6

Henry had donned black that day, out of respect for his first wife, Katherine of Aragon, whose body was being buried in Peterborough Abbey with all the honors due to the Dowager Princess of Wales, for she

was the widow of his brother Arthur Tudor, Prince of Wales. Having had his own marriage to her declared null and void in 1533, on the grounds that he could never lawfully have been wed to his brother’s wife, Henry would not now acknowledge her to have been Queen of England. Nevertheless, he observed the day of her burial with “solemn obsequies, with all his servants and himself attending them dressed in mourning.”

7

He did not anticipate that, before the day was out, he would be mourning the loss of his son with “great disappointment and sorrow.”

8