The Lake of Dreams (53 page)

Epilogue

ON THE NIGHT BEFORE YOSHI AND I LEFT THE LAKE OF Dreams, our last night in the airy darkness of the cupola, I lay awake for a very long time, searching for constellations. Scorpio and Sagittarius were visible; I traced the lines between the stars and wondered, as I often had before, how these intricately imagined characters had ever been assigned to such sketchy patterns in the sky. I wondered how these same stars might look from another perspective—say, from the moon. Next to me, Yoshi slept, his hair dark against the sheets, his breathing steady, and a comfort, like the sound of the waves against the shore. We’d woken weeks ago to the uneasy shifting of the earth, and now we were here, our known universe having altered in ways we never could have imagined.

I watched the stars, fixed and burning in the night.

Was it a dream, what happened next, or a kind of waking vision? Did I sleep? The same patterns of stars were visible, the same curved edge of the moon, but I was standing in the shallow water on the shore, my feet sunk deep into the smooth shale beach, waves splashing my knees and small fish swimming around my ankles. My toes dug deep into the stones, flowing out like roots, and my arms reached like branches to embrace the sky with its scuttling clouds, its beautiful pale round moon. My fingers, far above, fluttered into leaves.

I sat up, exhilarated. The air was soft, and Yoshi’s legs were tangled with mine; I eased myself free and climbed across the futon to the window. There was the moon, full and tranquil in the sky, making a path of light across the black expanse of water.

The wind stirred softly. I thought of Rose, of the chalice she’d taken, lost from her things or stolen again or sold and melted for the silver, of her stained-glass windows, her rows of vine-woven moons, and of the people in the Wisdom window, their arms lifted to the sky. I remembered my mother’s tulips, radiant, emerging from their leaves, delicate cups swaying on their stems. The singing bowls by my bed in Japan, and a goblet forming, flowerlike, at the end of a fragile glass stem.

I lifted my arms like the people in the window, my legs and torso like a stem, my arms a crescent curve. Male or female, it didn’t matter. Then or now, no difference.

I was a tulip, a cup, a calyx.

I was, in that moonlight pouring down, a chalice.

My dream stayed with me in the weeks and months that followed, but I didn’t share it with anyone except Yoshi. It seemed best left in metaphor, akin to the herons rising at the edge of the pond. Best left unnamed. I didn’t want anyone to laugh at me or raise their skeptical eyebrows or to simply not pay attention. I thought about it, though, every time I saw a flower blooming, a person dancing, or hands cupped to lift water.

Yoshi and I flew back to Japan, taking one train and then another and finally walking down the cobblestone street to our apartment, which was just as we had left it so many weeks before. We cleaned it out entirely, selling our appliances and giving away everything we couldn’t ship to our next life in Cambodia. For those were the jobs, finally, that had appealed to us, the jobs we’d been offered and had taken. My father had fought in Vietnam and he’d written about Cambodia in the letters my mother had saved, bound together with a piece of green ribbon. My mother had a photo of him standing in front of the Royal Palace. I didn’t know much more than that, but the connection, however tenuous, made the decision to go there feel right. So we packed and cleaned. The earthquakes had eased—the underwater island had finally formed. On our last day there, Mrs. Fujimoro gave me a beautiful silk scarf, and in return I gave her a kaleidoscope made of brass with hundreds of shifting pieces of glass. We bowed to each other in the street.

By mid-October, we’d returned to The Lake of Dreams for a final visit. We sat on the patio, the leaves edged with gold or orange or flaming red against the vivid blue sky, while I unwrapped a box that had arrived, searching through the thick layers of tissue paper to find two small stemmed glasses made of delicate green glass, the sides paper-thin, translucent. Inside the box, a card said, simply:

For Your Wedding, from Keegan and Max

. I handed one to Yoshi, imagining how it had taken form, the glass growing liquid and the cup emerging on the green glass stem—its delicate, human shape.

When Yoshi and I were married, we exchanged these cups in the Japanese tradition. We had the ceremony in the Wisdom chapel, with the Reverend Suzi Wells presiding, our friends and family filling the pews, and the women in the windows all around us, Rose and Frank somehow present, too. Ned read from the Song of Songs, and I asked Zoe, who was staying with my mother while her parents were on a cruise, to read a poem she’d written for us. Zoe had cut her hair short and gotten a tattoo of a little butterfly on her collarbone, all of which made her look younger and more vulnerable than she would ever have intended. Yoshi’s parents flew in from Helsinki, and sat next to my mother and Andy. Iris came with Carol and Ned, and Julie brought her boyfriend. Oliver came with his wife, and Stuart Minter brought his partner, Alex. Blake and Avery were there, too, though they sat at the back and didn’t stay for the reception; their son had been born just the week before and they were still dazed, still tired, reluctant to leave him. They named him Martin, after our father.

Art and Austen sent a gift—a set of white plates—which I gave to Goodwill, unopened.

After the wedding we lingered outside, the leaves vibrant reds and yellows against the blue autumn sky.

Three days later, we flew to Phnom Penh.

The beauty and the poverty here engulfed us like the heat; we wandered down the sunstruck streets, through market stalls with baskets of bright carrots or greens or whole fish, past the restored colonial buildings and shacks built from thatch and tarps. The scars of the past are visible everywhere, especially on the outskirts of the city—here a blackened stairway that ends in the sky, there a pond, perfectly round, which began as the crater of a bomb. I glimpse this in the faces of people, too, the past jutting like sharp stones into the swift currents of the present, and I am humbled every day by the suffering and the resiliency that I witness.

Yoshi took a job with an NGO that monitors the development of water resources along the Mekong River as it flows from China through Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia. What happens with these dams will matter to the future of this river and the people who live here for generations, and Yoshi comes home every day full of energy and ideas. My work, too, is good, though my own job came, surprisingly enough, not through any of my former contacts but through Suzi, who knew of an ecumenical group here working to improve the lives of rural women. I travel into the countryside and help set up foot-powered treadle pumps. They are made of bamboo and metal pistons and families take turns running them to collect fresh water from their wells. Everything begins with water. It helps the gardens, and when the families sell their surplus vegetables, they use the money to buy chickens for eggs or a cow for milk or to send their children to school. The program has grown so much that lately my focus is shifting to training others to demonstrate the pumps and travel to the provinces.

We live at the edge of the Mekong, one of the world’s great rivers. Every year when the monsoons come, the river fills and presses so hard against the sea that it changes its direction and flows north to flood the Tonle Sap, the great lake that the Cambodians call Creator Lake for its profusion of life. Graceful boats travel across the surface of the water and men lean to cast their nets, fishing. I think of my father, of course, but without the sadness I carried with me for so many years.

The boats are vessels, carrying the fishermen out each dawn. Long and narrow, they curve at the ends, arced like crescent moons. The heart is a vessel, too, pulsing blood in its orbit through the body, and in English the word

to bless

comes from the Old English

blestian,

or “blood.” The challenges in this place are real and sometimes very difficult, but I’ve learned to slow down and look for beauty in my days, for the mysteries and blessings woven into everything, into the very words we speak. I stand each morning at the edge of the balcony and watch the boats skim across the water. I feel the blood beating through my veins—vessels, too.

I listen. Not to locks anymore, but past the stillness to the deepest longings of what the mystics would call my true self, something I have come to understand as prayer. This is Rose’s greatest legacy to me. Her cloth hangs in our house, against the painted concrete wall; Iris gave it to us as a wedding present. Last year, during the slow, hot season and then the sudden time of rains, as I grew as round as one of Rose Jarrett’s interlocking moons, as I swelled like the river beyond our little house, I thought of Rose so often. When our daughter was born at the end of the cool season, we named her Hannah, after no one at all, though it’s true that we got the idea from the Japanese word

hanashobu,

which is a kind of iris that grows in marshy land. It’s true, also, that we sometimes call her Hannah Rose.

A few months after she was born, we had a lunar eclipse. Yoshi and I sat all evening on the balcony to watch the great pale moon rising over the river, a shadow falling over its edge, slowly eroding its light. I thought of Joseph Jarrett, waking from his dream to the light of the comet, and of Rose, walking home alone through the vineyards on that same night, more alive and terrified than she had ever felt before.

Near the end of the eclipse Hannah stirred from her sleep. Yoshi went inside to get her, moving through the rooms, talking to her softly. Then he brought her out to the balcony. “Look,” we said to her that night. “Sweet girl, look, the moon.” She saw it, emerging slowly from the mouth of the shadow, and laughed, reaching for the sky as babies will, as if she could grasp the moon in one small hand and slip it into her mouth like a wafer.

She laughed again when she couldn’t catch it, and reached higher, and we held her up. This would not last, of course. Soon, she’d be frustrated or hungry and we’d go inside, leaving the night sky with its burning stars. But for that moment the river flowed like black glass and we stood gazing at the wild, pale beauty of the moon, waiting to see how the world would shift, and change.

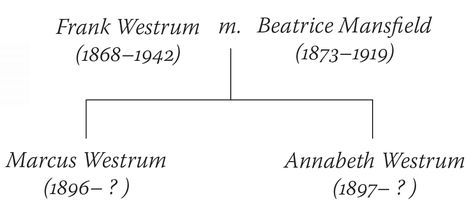

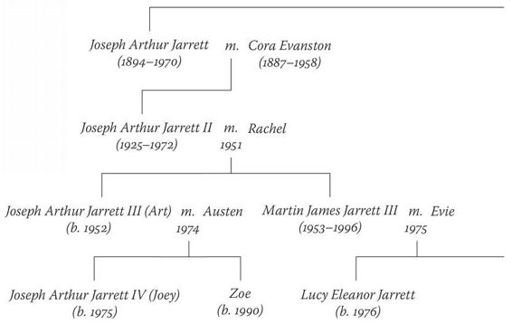

THE JARRETT FAMILY

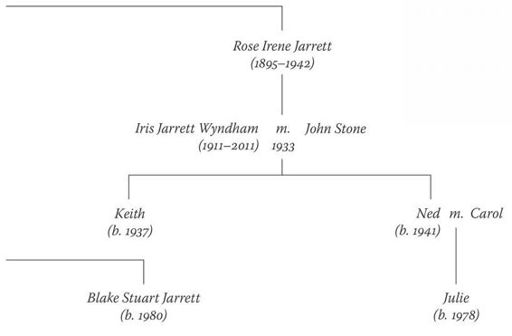

THE WESTRUM FAMILY