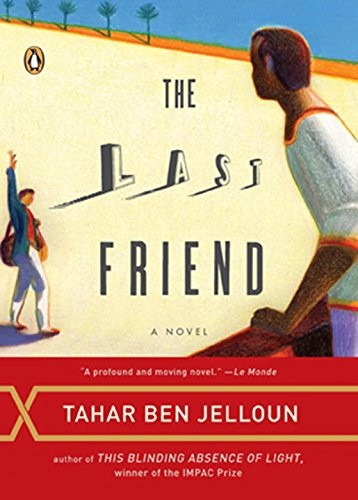

The Last Friend

Annotation

Tahar Ben JellounThe Last Friend, the novel from internationally acclaimed author Tahar Ben Jelloun, winner of the 2004 International Dublin/IMPAC award, is a Rashamon-like tale of friendship and betrayal set in twentieth century Tangier. Written in Ben Jelloun's inimitable and powerfully direct style, the novel explores the twists and turns of an intense thirty-year friendship between two young men struggling to find their identities and sexual fulfillment in Morocco in the late 1950s, a complex and contradictory society both modern and archaic.

From their carefree university days through their brutal imprisonment and ultimate release, the two rely on each other for physical and psychological survival, forging bonds not easily broken. Each narrator tells his version of the story, painting a vivid portrait of life lived within and in opposition to the moral strictures of North Africa.

Set against a backdrop of repression and disillusionment, The Last Friend is a tale of loss of innocence and a nation's coming of age.

"In his affecting new novel, Moroccan-French novelist Ben Jalloun (This Blinding Absence of Light) eloquently portrays postcolonial political unrest in Morocco through the long, ultimately ruptured friendship between two men. The novel is set over 40 years of Moroccan history, beginning in 1960 (a few years after Moroccan independence from France), when the two friends, Ali and Mamed, attend a French school in Tangier. The story tracks their joint political activism and imprisonment in the mid-'60s, professional and romantic successes, and marital disappointment. The two voices share the narrative evenly: first, Ali, an academic, tells his side of their falling-out. Mamed, a doctor who in later years moves with his family to Sweden, ails from a 'strange, neurotic relationship with [his] homeland' and, eventually, from lung cancer. Mamed precipitates a self-protective rift with Ali before dying. A long posthumous letter to Ali explains that Mamed had hoped to spare their friendship from the ravages of death – and yet, has Mamed acted finally from jealousy and spite? Their friendship becomes a journey through their Moroccan heritage, skillfully navigated by Ben Jalloun." Publishers Weekly

The Last Friend

Translated from the French by Kevin Michel Cape and Hazel Rowley

PrologueI received a letter this morning. A recycled envelope. The postmark and date were hard to make out over the stamp of King Hassan II in his white jellaba. I recognized Mamed's uneven handwriting. In the top left-hand corner, "personal" was underlined twice. Inside was a yellowish sheet of paper. A few lines, harsh, dry, final. I read them over and over. It wasn't a hoax, or some kind of bad joke. It was a letter intended to destroy me. The signature was my friend Mamed's. There was no doubt about it. Mamed, my last friend.

I Ali1

Mamed always used to say, "Words don't lie. Men lie. I'm like words." He would laugh at his own joke, pull a cigarette from his pocket, and slip into the boys' bathroom for a secret smoke. It was his first of the day, and he relished it. We would wait for him, on the lookout for the principal, Monsieur Briancon. We were afraid of him; he was strict and unyielding, as ready to give detention to his own two children as to any unruly students.

Monsieur Briancon was not likely to become any more lenient, especially after his oldest son was drafted for military service in Algeria. This was i960. Algeria was already in the throes of war. Once in a while, Monsieur Briancon would talk with Monsieur Hakim, our Arabic teacher, who also had a son in the army-on the other side, fighting with the Algerian National Liberation Front. The two must have talked about the horror and ultimate absurdity of the war-and about the indomitable spirit of the Algerians, determined to recover their independence from French colonial rule.

Married was short, with close-cropped hair and an intelligent face revealing his wry sense of humor. He had a complex about his small, skinny physique, convinced that girls wouldn't pay attention to him until he spoke. He charmed them with his gift for language, made them laugh-but he was just as capable of making cruel remarks. He was always ready for a fight, so other boys rarely provoked him. We became friends when he came to my defense against Arzou and Apache, two delinquents who had been thrown out of school for theft and assault. One day they were waiting for me just outside the school, trying to bait me, chanting: "The kid from Fez is a swine! He's a Jew!"

In those days, people in Tangier who had immigrated from Fez were undeniably discriminated against. They were known as "the insular people." Tangier still had the prestigious status of an international city, and its citizens considered themselves privileged. Mamed stood between me and the two bullies; he made it clear that he was ready and willing to fight to protect his friend. Arzou and Apache backed off. "We were just kidding," Arzou said. "We don't have anything against you pale-skins from Fez. Like the Jews. We don't have anything against them, but they always seem so successful. Come on, we were just kidding…"

Mamed said I was too white and told me to go to the beach to get a tan. He added that he, too, thought people from Fez had the same traits as the Jews, but he admired them, even though he was a little jealous of their special minority status in the city. He said people from Fez, just like the Jews, were calculating and tight with their money, intelligent, often brilliant; he wished he could be that thrifty. One day, he showed me an article claiming that more than half the population of Fez was of Jewish descent. The proof, Mamed said with a laugh, is that all family names starting with "Ben" were Jewish. They were Jews from Andalusia who had converted to Islam. "Think how lucky you are," he said. "You're Jewish without having to wear a yarmulke. You have their mentality, their intelligence, but you're a real Muslim, like me. You win on both counts, and you're not harassed the way the Jews are. Of course people are jealous of you. But you're my friend. You just need to change the way you dress, and be a little less cheap."

Seen from Tangier, Fez appeared to be a city beyond the reach of time-or more precisely, a city rooted and stuck in the tenth century. Nothing, absolutely nothing, had changed since the day it was built. Its beauty lay in its relationship to time. I realized that I had left behind an ancient era. After a single day's journey I found myself in the twentieth century, with dazzling lights, paved streets, and cars-a cosmopolitan society with several languages and currencies.

Mamed made fun of me, telling his friends I was a relic from prehistoric times. He went on and on about the traditions of old Fez, a city that had always resisted modernization, implying that Tangier was far superior to "that old place" so admired by tourists. Mamed's father, intelligent and cultured, was a prominent citizen with friends in the British consulate. He corrected his son. " Fez is not just any old city. It's the cradle of our civilization. When our Jewish and Muslim ancestors were expelled from Spain by Queen Isabella, they took refuge in Fez. The first great Muslim university, the Qarawiyyan, was built in Fez -by a woman, no less, a rich woman from the Tunisian holy city of Kairouan. Fez is a living museum, and should be considered part of our universal heritage. I know, our treasures aren't so well preserved, but there's no city in the world like it, and for that alone, it deserves respect."

I liked this refined, elegant man. He would lend me books, asking me to pass them along to his son, who had never cared much for reading.

Mamed's house was just a few steps from the school. Mine was on the other side of the city, in the Marshane district overlooking the sea, more than twenty minutes away on foot. He used to invite me to his parents' for afternoon tea. The bread came from Pepe's, a Spanish bakery, and I thought it was delicious. At home, my mother made the bread herself, and it was clearly inferior. Mamed, though, preferred my mother's bread to Pepe's. "That's real bread," he'd say to me. "You don't get it. It's homemade. That's the best!"

2Our friendship took a while to develop. When you're fifteen, feelings fluctuate. In those days, we were more interested in love than friendship. We all had girls on the brain. All of us, that is, except Mamed. He thought courting girls was a waste of time, and never went to the surprise parties held by the French students. He was afraid that girls would refuse to dance with him because he was short, or not attractive enough, or because he was an Arab. He had good reason to think this. At a birthday party for one of his cousins whose mother was French, a pretty girl had rudely rejected him. "Not you, you're too short and not good looking!"This offhand comment took on exaggerated proportions.

Now all our discussions at recess revolved around France 's war in Algeria, colonialism, and racism. Mamed didn't joke anymore. Naturally, I took his side, and agreed with everything he said. Our philosophy teacher read to us from Frantz Fanon's new book,

The Wretched of the Earth,

and we spent hours discussing it. At the time, we all sided with Sartre rather than Camus because Camus had written: "Between my mother and justice, I choose my mother." Already very engaged in politics, Mamed said he was reading Marx and Lenin. I wasn't interested, even though I was fiercely anticolonialist. I read poetry, classical and modern.

The Wretched of the Earth,

and we spent hours discussing it. At the time, we all sided with Sartre rather than Camus because Camus had written: "Between my mother and justice, I choose my mother." Already very engaged in politics, Mamed said he was reading Marx and Lenin. I wasn't interested, even though I was fiercely anticolonialist. I read poetry, classical and modern.

Mamed became a militant. I fell in love, which bothered him. Her name was Zina; she was dark and sensuous. For the first time, it occurred to me that he might be jealous of me.

When I confided in him, he teased me. I made light of it. But deep down, I knew he didn't like this intrusion into our friendship. For him, it was a waste of time and energy. He readily admitted that he "beat his straw" every day. He used the Spanish word for straw,

paja

,

to mean masturbation, and joked about this with his friends. The girls were embarrassed, and hid their faces, laughing. Mamed took the joke one step further, referring to girls as "exquisite straws."

paja

,

to mean masturbation, and joked about this with his friends. The girls were embarrassed, and hid their faces, laughing. Mamed took the joke one step further, referring to girls as "exquisite straws."

Our group picnics became a time to get even. Mamed wanted to play "the defect game," as he called it, which involved each of us enumerating our flaws, one after the other, especially private, secret ones. He started with himself to show us. "I'm short, ugly, hard to get along with, cheap, and lazy. If I'm bored at dinner, I fart. You can't take me anywhere. I lie more often than I tell the truth. I don't like people and I like to be mean. Now it's your turn!" He looked at me defiantly. I launched into self-criticism by exaggerating some of my personality traits, which pleased him. My girlfriend didn't like this game, and threatened not to come out with us any more. Mamed silenced her by threatening to reveal secrets he claimed to know about her. This upset me. He told me later this was a good tactic because everyone has secrets they don't want revealed.

The girls liked him, actually. Khadija told everyone she liked him, even when he wasn't talking. We were all relieved to hear this. If Mamed had a girlfriend, maybe he wouldn't be so mean. He wasn't in love, but he saw Khadija on a fairly regular basis.

One day, we were having a picnic and everything was going fine when Mamed suggested we play the defect game again. This time, you had to list the faults of the person you knew best. Poor Khadija turned pale. Mamed started talking about the number twelve. Khadija apparently had twelve flaws that would make any man run in the other direction, and others that would turn him into a woman-hater forever. It was impossible to stop him. We protested, but he was off and running. We were scared, he said. We were cowards. Zina turned up her radio as loud as it would go to drown out his cruel words. Dalida, the Franco-Egyptian singer, was singing "Bambino." Mamed, furious, grabbed the radio and threw it in the water.

"You should listen to me," he said. "We're here for the truth. Why should we encourage the social hypocrisy paralyzing this country? Yes, Khadija has twelve faults. She has at least as many as the rest of us, so what are you all afraid of? She's eighteen and still a virgin. She prefers to be sodomized rather than to spread her legs. She'll suck but she won't swallow. She wears deodorant instead of washing. When she comes, she screams the names of the prophets. She sneaks alcohol. When she doesn't have a boyfriend, she sticks candles up her ass."

Other books

Tree Girl by T. A. Barron

Letters to Her Soldier by Hazel Gower

Knight Fall (An Erotic BBW Romance) by Maddix, Marina

Crime Writers and Other Animals by Simon Brett

The Late Monsieur Gallet by Georges Simenon, Georges Simenon

Needing Sir In Charge (Dark Possessions Book 2) by Nadia Nightside

Touchstone (Meridian Series) by John Schettler, Mark Prost

Mafia Princess by Merico, Marisa

Indiana Jones and the Army of the Dead by Steve Perry