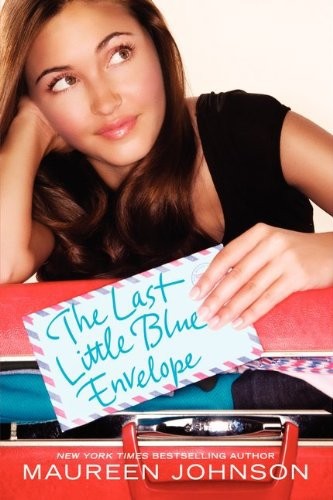

The Last Little Blue Envelope

Read The Last Little Blue Envelope Online

Authors: Maureen Johnson

The Last Little

Blue Envelope

maureen johnson

To all the jars. You know who you are.

London is a riddle. Paris is an explanation.

—G. K. Chesterton

Contents

It was that time of day again. Time to stare at the question, the two lines of black on an otherwise blank page.

Question:

Describe a life experience that changed you. What was it, and what did you learn? (1,000 words)

This was the most general college application essay, the one that required the least research. Ginny had completed all the other steps—asking for transcripts, groveling for recommendation letters, two sittings of the SAT, one AP exam, four essays on various subjects. This essay was the very last thing she had to do. Every single day for the past three weeks, she opened the document and stared at the question. Every day, she started to type the answer, then erased what she had written.

She took a deep breath and began to type.

My aunt Peg died last May. At least, that’s when we found out about it. She left the country two years before, and we didn’t really know where she was. But then we got a call from a man in England who told us she had died of brain cancer. A few weeks later, I got a package that had thirteen blue envelopes in it. . . .

How exactly was she supposed to explain what happened over the summer? One day, thirteen little blue envelopes containing strange and very specific instructions from her aunt showed up, and then Ginny—who had never been anywhere or done anything—was suddenly on a plane to London. From there, she went to Paris, to Rome, to Amsterdam and Edinburgh and Copenhagen and across Germany in a train and all the way to Greece on a slow ferry. Along the way, she had met a collection of stone virgins, broken into a graveyard, chased someone down Brick Lane, been temporarily adopted by a strange family, been fully adopted by a group of Australians, made her stage debut singing Abba in Copenhagen, been drawn on by a famous artist . . .

. . . it was a bit hard to summarize in one thousand admissions-committee-ready words.

She looked at the calendar she had made for herself out of sticky notes on the wall next to her desk. Today’s note read: Sunday, December 12: FINISH ESSAY!!!!! NO, SERIOUSLY, THIS TIME FINISH THE ESSAY!!!!!! And a few lines down, the due date: January 5. She pulled it off the wall and tossed it into the trash. Shut up, note. She didn’t take orders from anything that had a glue strip.

Ginny put her feet up on the edge of her desk and tipped her chair back. She had always thought applying to college would be exciting. Living away from home, meeting so many new people, learning new things, making a few poor life decisions . . . the thought of it had kept her going all through high school. But after last summer, college didn’t seem like such an adventure anymore. She started idly scrolling through the websites of the colleges she was applying to. All of them were trying to sell her a future in the same way they might try to sell her some mascara (“Longer, fuller lashes! New formula! Look!”

Close-up of unnaturally long lashes, thick with something

) or a weight-loss product (“I lost 25 pounds!”

Image of woman twirling around in dress next to picture of her former self

).

The photos were all the same, for a start. Here was the one with the smiling and carefully composed group wandering down the tree-lined path in the sunlight. The close-up of the person at the microscope, the wise professor leaning over his shoulder. There was the one of cheering people in matching shirts at a basketball or football game. It was like there was a checklist that all the schools had to follow. “Have we included ‘professor pointing at blackboard full of equations’? Do we have ‘classroom of smiling, engaged students staring at nothing’?” Worse than that were the catchphrases. They were always something like: “We give you the keys to unlock the door of success.”

She dropped the legs of the chair back down to the floor and flipped back to the blank page and the question.

The letters arrived last May . . .

. . . and were promptly stolen by some dudes on a beach a few weeks later.

Ah yes. That was the other problem with this essay—the horrible ending. In August, she was on the Greek island of Corfu, standing on the white sand of a gorgeous beach. The only envelope she had left to open was the very last one, and she decided to do this just as soon as she had a little swim. She had been on a ferry for twenty-four hours, baking in the sun on the deck . . . and the water here was so very, very beautiful. Her friend Carrie decided to swim naked. Ginny went into the warm, clear waters of the Aegean wearing her clothes. They left their backpacks in the care of their three male friends, who fell asleep on guard duty.

High above, on the white rocks overlooking the water, two boys on a scooter stopped and surveyed the scene. Ginny was bobbing up and down in the waves and watching the ocean meet the sky. She remembered the sound of Carrie screaming and yelling. She remembered climbing over some rocks to find Carrie dancing around in a towel, naked and crying and saying something about the bags being gone. Ginny looked up to see the scooter ripping away from the scene, back up the rough path, back to the road above. And that was it. Letter number thirteen had been ripped right out of her life by some petty thieves who wanted her crappy backpack.

Lesson learned? Do not go swimming in the Aegean and leave the single most important document in your life in a bag on the beach. Take that, College!

Her eyes drifted away from the essay to the little red light in the corner of her screen. The light that symbolized Keith.

Keith was the actor/playwright she met when she was following the directions in her third letter, the one in which she had to give five hundred pounds to a starving artist. She found Keith’s play in the basement of Goldsmiths College and she bought all the tickets for the entire run, making him the first person to ever sell out the tiny student theater he was working in (also accidentally ensuring that no one would ever see his show). He was intense, hilarious, bizarrely confident, handsome . . . in a scruffy-poor-London-art-student way. But most mysterious of all, he was fascinated by

her

. He called her his “mad one.”

To be clear—and she reminded herself of this fact daily—Keith was not her boyfriend. They were “kind of something.” That was how they had left it, in those exact words. Their relationship was deliciously and frustratingly ambiguous, always flirty, never defined. When Ginny first returned to America, they were in touch every day. The time difference made it tricky—he was five hours ahead—but they always managed it.

Around Thanksgiving, he got into some show he called a “panto,” so between rehearsals and his school schedule, his time online had decreased dramatically. For the past few weeks, Ginny had perched herself at her desk every night, waiting for that little light to turn from red to green, signifying that he was online. It was seven thirty now, which meant it was twelve thirty in London. Tonight was probably going to be one of those nights he never came online at all. She hated those nights.

She checked her email instead. There were several messages, but the one that caught her eye was from someone named [email protected]. Someone else from England was trying to reach her—someone she didn’t know. She opened it.

What she found was a picture. A big blue square that filled the screen. It took her brain a moment to realize that it was a scan of a piece of blue paper with very familiar handwriting. It took almost a full minute more for her to fully accept what she was seeing.

#13

Dear Ginny,

Let me tell you about the division bell. The division bell will tell you a lot about England. You like to learn about England, right? Of course you do.

See, in Parliament, when they have a vote, they shout aye or no. The Speaker says, “I think the ayes have it” or “I think the noes have it,” depending whichever side is at its shouty best. Sometimes, though, when it can’t be determined which side has won, they have to have what is called a rising vote. A rising vote means just that—you have to rise up and stand on the yes side or the no side so you can be counted. There is an adorable, kindergarten-like quality to this, right?

Following on the kindergarten theme . . . sometimes members of Parliament are out at recess when these votes happen. Instead of being in the sandbox, though, they are usually at the pub. So, local Parliament pubs are sometimes outfitted with a division bell, which rings when one of these votes is about to take place. When it rings, the members hurry back and stand on the yes or no side.

The division bell is ringing for you today, Gin.

You’ve done a lot in the last twelve envelopes, if you have in fact completed all that was contained in them. For all I know, you’ve read these letters from your sofa in New Jersey. But I trust you. I think you’re exactly where I suggested you should be: on a ferry in the Greek Islands.

If you really wanted to, you could go home right now. Maybe you’ve had enough. Or . . .

. . . or you could go back. Back the way you came. Back to London.

Do you want to go on? Ding, ding. Yes or no?

I’ll be honest with you, from here on out, things get a little weird. If you are ready to stop, do it. Take it from someone who knows—if you feel the need to go home, listen to that need and respect it.

Think it over on the beach for a while, Gin. Should you decide to go on, you can go to the next page and . . .

At this point, the letter stopped. At the bottom, below the image, was a short message:

Sorry to interrupt. You don’t know me, and likewise, I don’t know you. As you can see, I possess a letter (actually, a series of letters) that seem to belong to you. But since this last letter contains very important information, I have to be sure that I am speaking to the right Virginia Blackstone. If you think this letter belongs to you, please let me know. My name is Oliver, and I live in London. You can reach me at this address.

For a moment, she did nothing. No movement. No speaking. She waited for the information to sink in. This was a page of the last letter. This was a task undone. This was the universe more or less demanding that she return to England at once and finish what she had started. This was fate. This was her brain going into hyperdrive.

The old Ginny had never traveled and knew no one in England. Old Ginny would think, plan, be cautious. But new Ginny needed a distraction, and a reason to see her kind-of-something non-boyfriend . . . and she knew someone who knew how to make unlikely things happen.

She got up and started to pack.