The Last Supper (20 page)

Authors: Rachel Cusk

*

We roam in the soughing pine woods. We lie by the water, talking. We peer at the Etruscan tombs, following dusty paths through fields of dry grass. There is the Tomb of the Chariots and the Tomb of the Attic Vases and the Tomb of the Funereal Couches. There are dome-shaped tombs like dirt-coloured igloos in the grass. We stare at them but we do not understand them: they are the core, the impenetrable kernel of this land’s mystery.

For four nights we sleep in the tent on its dry, rustling carpet of leaves. The children sleep deeply, soundlessly. We lie close together. In the darkness there is no perspective. It is like being held in the palm of a hand.

All day and all night I am half-asleep and half-awake. I am thinking about the future, though these thoughts are wordless and indistinct. They are like running water, a single entity. They pour towards an edge, a precipice, and tumble over the side. I do not want to go home. More precisely, I don’t know

how

to go home. My consciousness runs swiftly, smoothly towards this edge and then tumbles over, a cataract. I need to find a path down out of these months in Italy. They stand behind us like mountains. To have climbed them, to have known their paths and peaks: in certain lights it has seemed that these are the dimensions of life itself, but lying in the tent I know this isn’t so. Life could become flat again, ordinary again. It is desire that is big and grand and treacherous; desire, not life. I remember the Apuan mountains, their abysses, their glinting white fastnesses of rock: we will pass them on the road home and look up from the flatlands at their awful faces. We will remember that we were once there. But we will pass them. We will stay on the road.

A big group of Italian teenagers arrives, and they pitch their tents around ours in a circle. They giggle and shriek and sing English pop songs all night. Our clothes are filthy; there is nowhere to sit, except on the ground. Our hair is matted and our tent is full of ants. We wake up on the fifth day and realise that we want to leave Baratti. We pack up the car, and follow this slender thread of desire north.

*

On the road outside La Spezia, the telephone rings. I have made some money: a South Korean publisher has bought the rights to one of my books, for a handsome sum. We cheer the South Koreans, zig-zagging madly across both lanes of the N1. It is late afternoon, thirty-nine degrees, the sky grey and turbid and pregnant-looking. We turn off at Rapallo, looking for campsites. The road is dense with traffic. We crawl into town and out the other side, and follow the road down the Portofino peninsula. It does not seem likely that we will find a campsite along this road: the hills rise in steep

green terraces to the right, and to the left plunge straight down to the sea. On the other side, back towards Rapallo, the cars have come to a standstill. The sky is clear here, and the sun is hot. A few people are getting out, to sit in the shade by the side of the road and wait. The rest keep their engines running and their tinted windows tight shut. Their forms can be glimpsed in the dark, air-conditioned interiors: they are like nocturnal animals, carved out of shadow, with strange glimmering accents embedded in their eyes and jewellery. There are some very expensive cars in the traffic jam. This is the rich Portofino crowd, whose giant yachts we see later in the harbour, dwarfing the narrow sunset-coloured terraces. But the peninsula is beautiful, as lush and romantic as a Giorgione landscape, with its faded pink

palazzi

, its villas sunk in the trees, its road winding above the water. The cars form a little packed rope of anxiety, weaving through the loveliness of a dream.

It is past six o’clock and the children are hot and fretful. The dust of Baratti is everywhere, in our clothes and hair, caked in our nails. There is no turning back: the road the other way is at a standstill. We are being forced along the peninsula like something being digested. We inch towards Santa Margherita, and when we get there we abandon the car and walk in search of a hotel. The cheap hotels are full. The expensive hotels are full too. We try the ugly hotels: I feel sure that in Italy the ugly hotels will always have space. Up a backstreet I find a hotel that is situated in the middle of a concrete multi-storey car park. The receptionist is sitting in a glass box in a grey-carpeted foyer, from where long, low-ceilinged grey corridors with rows of identical doors extend out to every side. Through the foyer window, five or six feet away, I can see cars going up and down the concrete ramps of the car park: that is the only view. No other human being is visible, except for the receptionist in her box. She wears a red uniform, like an air hostess. She speaks to me through a grille. She tells me that the hotel is completely full.

We jump back in the car and re-enter the traffic jam. It is dusk now, and the streets of Santa Margherita are full of people. They sit in the cafes with exquisite drinks, and walk freely out along the harbour in the sea breezes and rose-coloured light. We gaze at them, parched and disconsolate. We have no choice but to go forward: the road back is paralysed. We crawl out of the harbour and along the coast. It takes twenty minutes to go a hundred metres. The sea softly rises and falls beside us, pink and blue; far out on the water, a boat catches the last gold of the sun on its ivory sail. We shuffle on, impacted in our metal box. In front of us the road curves round out of sight: we strain impatiently to see what will be there. At last, tortuously, it discloses itself, a wooded bay, with a great white edifice standing above the water in a sweep of green lawns. It is so white, so sparkling: it is like the palace of some fabulous neurasthenic billionaire. A driveway rises to the porticoed entrance, and at the end of the driveway there is a magnificent pair of gates, with a brass plaque reading

Grand Hotel Mira

mare

. A man in a cap and white uniform is standing by the gates. We look at him, and he looks at us. He smiles, and gives a slight bow. As if of its own volition the car leaves the road, slewing right, barging through the traffic, past the brass plaque and up through the gates into the perfumed chirruping gardens, where it pauses to allow the uniformed man to lay his white-gloved hand gently on the rim of the filthy window. He is sure there will be a room available. When we are ready he will take our car to the hotel car park. If we indicate what luggage we require for the night, the porters will take it directly from the car to our room.

He wishes us a most pleasant evening at the Grand Hotel Miramare.

*

The porters handle our noxious bags with rigorous politeness. No one looks at our feet, our clothes, our hair. The man at the desk offers us a suite: it is all he has left. We ask if he couldn’t possibly find us something cheaper. No, no, he says, this suite

is positively the only room free in the hotel tonight. He considers its freeness, there in front of us: perhaps, after all, this suite is something unwanted, passed over, like a woman past her prime. And here we are, late in the day, a match. It is past seven o’clock in the evening. As the suite remains unwanted, he will give it to us half price.

Our suite has a balcony facing the sea. In the white-tiled bathroom with its gold-plated taps we confer. We examine our luck, the snowy towels and bathrobes, the slippers with the hotel’s name stitched across the toe, the miniature gold-capped bottles of bubble bath. We lie on the firm, enormous beds. Beneath our balcony, in the garden, there is a swimming pool. It is surrounded by lawns, and beyond them, the sea. We run downstairs and jump in, in the last light. There have been so many arrivals, so many cycles of desire and satisfaction, mounting and mounting through hours of chaos and uncertainty, building like a wave and then breaking, foaming with completion. Here is another: the empty oval of water that lies in the thick grey and violet dusk, the deserted lawns falling into darkness, the pale, quiet sea. A gardener in uniform moves among the shrubberies with their hedges and ornamental trees. Their forms are sculptural, abstract, hewn from big blocks of shadow. The man is indistinct, moving among the shadowy forms. He is less clear, less substantial than they. We jump into the water. It is salty, and dark in its depths. We break its membrane: we send furrows and folds travelling across its surface. The light has nearly gone. The children swim away into darkness. They leave a wake behind them, a path of ripples that is a kind of memory of themselves, a record etched in the water. Their small heads make two round, black, dense shapes in the distances of the pool. Behind them the path erases itself: this is how they will live, advancing themselves through the yielding, unremembering world, holding their heads upright above the surface. It is half-terrible, that they should have to support the mystery of their own selves, just as a work of art must support its own mystery and bear its own fate, however beautiful and

beloved it is. For it seems so relentless to me there in the water, the erasing, the dissolving, the rubbing out of each minute by the next. Almost, it is unbearable. It strikes me that the glory of art is the glory of survival, for survival is an inhuman property. It is an attribute of mountains and objects, of the worthless toys in the children’s bedroom at home that will outlive us all. That which is human decays and disappears: only in art does the quality of humanity favour survival. Only in art is a record kept of an instant, that the next instant doesn’t erase.

The sky is steadily filling with cloud: it moves over the peninsula in a body, vast, like a dark glacier. For a while it builds around the bay, forming great cliffs at its edges that are gilded with paleness by the moon. Then the moon is engulfed and the cloud spreads out over the water. We get out and run back upstairs in our towels. Waiters are setting out dishes of nuts and olives in the hotel bar; the restaurant has lit its chandeliers, which blaze above the waiting tables. We dart up the grand marble staircase and along a corridor as wide as a boulevard to our room. But we meet no other guests; there is no one to shock with our attire, our dripping hair. And later, when we come down again, the blazing restaurant is still empty; the olives still sit mounded in their dishes. We do not intend to eat in the restaurant: a leather-bound menu on a gold plinth beside the door discloses the prices. But we stand there nonetheless, gazing through the doorway at the spectacle of its deserted grandeur, its inexplicable readiness, with its sparkling silver and crystal, its thick white napkins folded into pyramids, its tablecloths and fancy-backed chairs, for an event that seems to hover just beyond the boundary of perception. It is as though a delegation of ghosts is expected, or as though the notion of wealth itself is tonight to be honoured and served, by the proud waiters who move among the tables making minute adjustments to the position of a glass or a fork.

Outside a warm wind is blowing. The sea is a field of dark inflections; the boats rock sleepily on their moorings. We walk along the road, into Santa Margherita, and find a table at a

packed little place by the port, where the heat and laughter and the smells of cooking, the deep wooden shelves of beautiful wines, the baskets of rough bread, the old

padrone

in his stained apron, the faded colour photographs of Italian landscapes, the glass cases of lemon tart and

tiramisu

, seem to distil all our manifold experiences into themselves; to become representative, even of things that bear no resemblance to them. Here are our travels, transitory but alive; here, again, is the reality, the moment that breaks and foams. We will not always live like this. We are going home, to work, to settle down, to send the children to school. Later, their teacher is discomposed

by their lack of familiarity with the conventions of the classroom. They have forgotten their maths, or perhaps it is merely that they have forgotten their place among their peers. They have forgotten how to live anywhere but at the centre of experience. Everything that now seems so real will soon be suspended; soon, the other reality will be unwrapped and reassembled. They are so different, these two realities. The first is the reality of the moment, of the sky as it looks tonight over Santa Margarita, of the

spaghetti alle vongole

and the satirical face of the

padrone

and the eczematic reproduction of Leonardo’s

Last Supper

that hangs in a cheap gilded frame beside our table. And the other: what is the other?

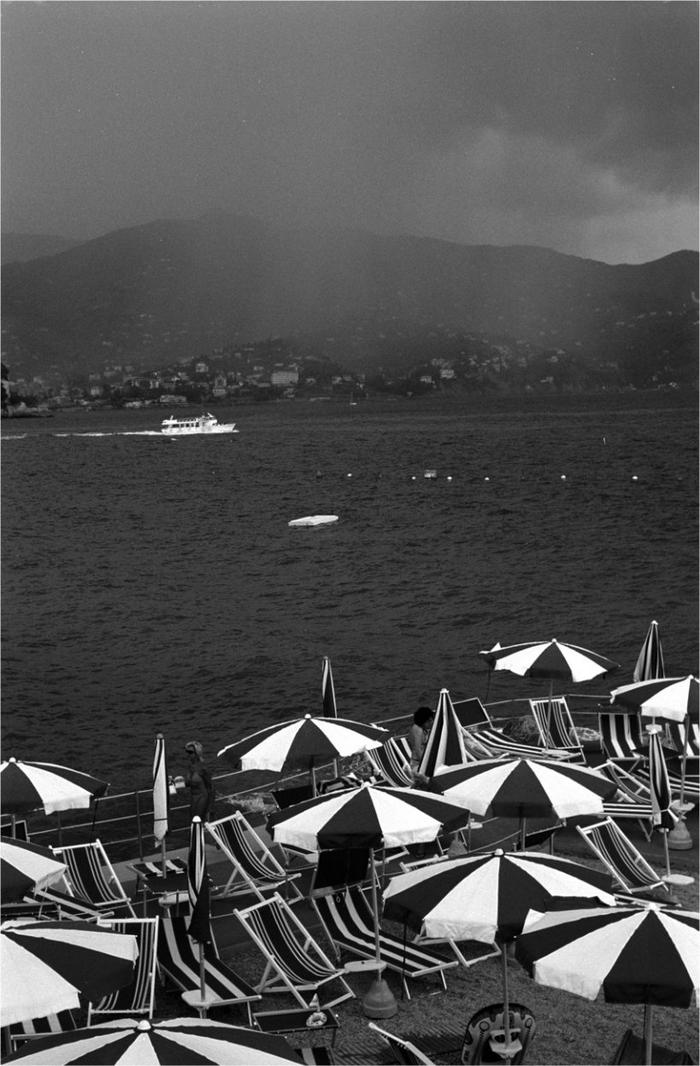

Beyond the steamed-up windows the storm breaks over the port. The water rushes down, hurling itself on the paving stones. It cascades off the awnings and runs in brown rivers along the gutters. Walking home we are soaked to the skin, but later, standing on our balcony, we watch branches of lightning illuminate the tossing surface of the sea, jagged paths of electricity that struggle briefly to find some route into the earth, and in their failure brilliantly expend themselves and are extinguished.

*

The children have made two friends: we go out to breakfast on the hotel terrace to discover that they have affianced themselves to the daughters of an American millionaire with a pockmarked face and small blue eyes that look wearily at something over your shoulder. The Americans are at the Miramare for a fortnight, and our children are the first playmates they have found since their arrival a week earlier. The mother comes across to look us over. She is tall, powerfully built, with a slouching, cowboyish gait; but she is strangely pale and flaccid-looking. She too has a weary, offhand demeanour: she stands beside her husband and the two of them tell us about their tour of Europe, reeling off a list of countries and capital cities with a striking lack of animation, so that Paris and Prague seem to deflate a little before our eyes. We are still struggling to digest

the notion of two whole weeks at the Grand Hotel Miramare. What strange, inexplicable luxury! The sun is shining once more: the other guests have come out for breakfast on the terrace. There are one or two bejewelled old ladies with tiny, fretful dogs, but otherwise they do not compose a particular type. They are all different, and they are all rich. The American woman does display a minor inconsistency: unlike the others, her clothes look as though she has worn them at least once before.