The Last Weynfeldt

Read The Last Weynfeldt Online

Authors: Martin Suter

THE LAST WEYNFELDT

First published in German in 2008 as

Der letzte Weynfeldt

Copyright © 2008 Diogenes Verlag AG Zürich

Translation Copyright © 2016 Stephen Morris

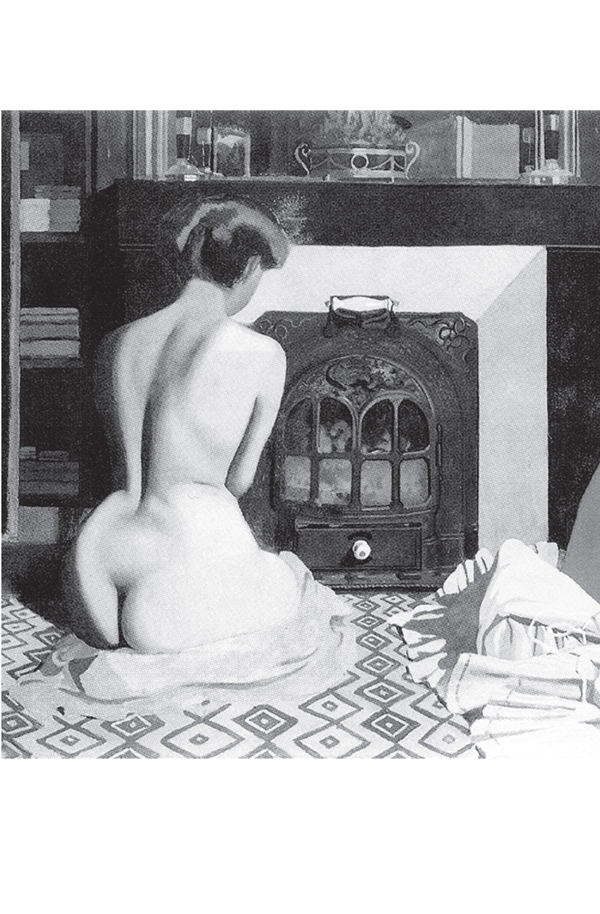

Inside cover image,

Femme nue devant une salamandre,

by Félix Vallotton, 1900, PD-US.

All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, television, or website review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

The translation of this work was supported by the

Swiss Arts Council Pro Helvetia.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Suter, Martin

[Der letzte Weynfeldt. English]

The Last Weynfeldt/Martin Suter; translation by Steph Morris.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-939931-27-6

Library of Congress Control Number 2015935266

I. Switzerland â Fiction

1

D

ON'T DO IT, HE WANTED TO SAY

. H

E COULDN'T

.

Adrian Weynfeldt fixed his gaze on the woman's pale, freckled fists clamped to the wrought-iron balustrade, knuckles glowing white. He didn't want to risk looking her in the eyes; she had chosen him as her witness, and he hoped that jumping without eye contact would be too impersonal for her.

Her bare feet poked through the gap between the balustrade and the balcony. Every toenail was painted a different color. He had noticed it last night. Red, yellow, green, blue and violet on the right foot; the same colors in reverse on the left, meaning that the two middle nails both gleamed green.

She hadn't extended the motif to her fingernails. They were lacquered with clear varnish, painted white where they protruded beyond the fingertip. They weren't actually visible this second, but he remembered them. Weynfeldt was a visual person.

The knuckles turned from white back to pink; she had loosened her grip. “It's only thirty feet,” he said quickly. “You might survive, but it wouldn't be much fun.”

The knuckles went whiter again. Weynfeldt shifted his left foot forward, level with his right, then inched the right a half step farther.

“Stay right where you are!” the woman said.

What was her name? Gabriela? He couldn't remember; he had no memory for names. “Sure. But if I stay where I am, so must you.”

She didn't say anything, but her knuckles remained white.

The lights were usually on all day in the office building across the street, with its neoclassical façade. Today was Sunday, still early in the morning. There were no people on the street; the streetcars which normally went by were few and far between, and only occasionally could a car be heard. Weynfeldt shuddered at the thought of the scene taking place on a weekday. The woman was wearing a black bra and matching black panties. At least he hoped she was still wearing the panties; the green canvas sheet which hung from the balustrade to provide privacy now obscured his view of her below the waist. And when he woke she had already been standing outside.

He wasn't sure what had woken himânot a noise, perhaps the unfamiliar perfume. He had lain there a while, eyes closed, trying to remember her name; her face he could see.

A little leaner maybe, less determined, more disillusioned. But the same pale, freckled skin, the same slightly slanted green eyes, the same red hair and, above all, the same mouth, the upper lip almost the same shape as the lower.

It was the face he'd been trying both to forget and to remember for years.

Adrian Weynfeldt had spent this Saturday night as he spent every Saturday night: in the company of his older friends. He had two circles. One was made up of people fifteen or more years younger than him. Among them he was seen as an exotic original, someone you could confide in, but also make fun of sometimes, who would discreetly pay the check in a restaurant, and help out occasionally when you had financial difficulties. They treated him with studied nonchalance as one of their own, but secretly basked in the glow of his name and his money. In their company he could visit clubs and bars he would have felt too old for otherwise.

His other group of friends was composed of people who had known his parents, or at least moved in their circles. They were all over sixty, some over seventy; a couple had already reached eighty. And yet they all belonged to his generation. Adrian Weynfeldt was born late to a couple who had remained childless for many years. His mother was forty-four when he came into the world; she had died nearly five years ago, shortly before reaching ninety-five, when Weynfeldt was fifty.

Adrian Weynfeldt had no friends his own age.

Last night he had been with his elderly friends, in the Alte Färberei, a traditional restaurant in a guildhall in the old town, only ten minutes by foot from his apartment. Dr. Widler had been there, his mother's doctor, increasingly listless in recent months, several sizes thinner and threatening to vanish inside his tailored suitsâhis wife Mereth all the more lively, her makeup, hair, and clothes impeccable as ever. And as ever, she took delight in contrasting her china-doll image with colorful language and vulgar remarks.

Remo Kalt joined them, Weynfeldt's recently widowed cousin on his mother's side, in his mid-seventies, wearing a black three-piece suit with a gold pocket-watch and a neat Thomas Mann moustache, as if he'd come from a portrait sitting with Ferdinand Hodler. Remo Kalt was an asset manager; he had looked after Weynfeldt's parents' capital and continued to manage it for their son. Adrian could easily have taken this over, but hadn't had the heart to deprive Kalt of his last remaining client. There wasn't much you could get wrong; these were not immense assets, though certainly solid, and conservatively invested for the long term.

They had ordered the

Berner Platte

, a shared meat dish featured on the menu throughout the winter. Dr. Widler had hardly touched a thing. His wife, a woman who had moved from willowy via slender to gaunt over the years, had taken two servings of everything â bacon, tongue, blood sausage, smoked ham. Kalt had kept pace. Weynfeldt had eaten like a man still vaguely concerned about his figure.

The evening was pleasant yet forced. Forced because Mereth Widler's provocative remarks had long begun to wear thin, and because everyone around the table knew this was one of the last times her husband would sit at it.

The Widlers left early, Weynfeldt drank one more for the road with Remo Kalt, and when shortly afterward they ran out of conversation, they ordered Kalt a taxi.

Weynfeldt waited with him at the entrance. The night was much too mild for February; it felt like spring. The sky was clear, and the moon rising high over the old town's steep roofs was almost full. The street was empty except for an elderly woman with an energetic spitz on a leash. They watched in silence: powerless, she let her dog walk her, stopping every time he wanted to sniff something, rushing to catch up when he wanted to move on, change direction, or cross the road.

At last headlight beams shone around the corner of the road, followed by a slowly-approaching taxi which stopped in front of them. They parted with a formal handshake, and Weynfeldt watched the taxi drive away, its sign switched off now, its brake lights red as it halted at the junction with the main road.

His route home included a stretch of the river and La Rivière, a bar he found it hard to pass at this time of night; it was nearly eleven p.m. He went in for a drink, as he so often did on the Saturday nights he spent with his elderly friends.

Two or three years ago La Rivière had been a rundown dessert café. Then it was taken over by one of the city's many gastronomic entrepreneurs, who had turned it into an American-style cocktail bar. Two barkeepers in eggshell-colored dinner jackets mixed martinis, manhattans, daiquiris and margaritas, served in sleek glasses. On Saturday nights a trio played smooth jazz classics at a subdued volume.