The Latte Rebellion (12 page)

Read The Latte Rebellion Online

Authors: Sarah Jamila Stevenson

Tags: #young adult, #teen fiction, #fiction, #teen, #teenager, #multicultural, #diversity, #ethnic, #drama, #coming-of-age novel

The turnout at our December 10th rally-planning meeting was even bigger than before. People were leaning against the tan-painted walls of Mocha Loco or finding space between the crowded tables to sit on the floor. Carey, Miranda, and I sat at a table up front with David Castro and pretended to be normal audience members, letting Leonard and Darla handle the heavy lifting.

Not speaking up was a bit harder than I’d thought; you should have heard the applause when they announced we were close to meeting our T-shirt sales goal.

I gleefully relived this scene more than a couple times over the rest of the week. And at this particular moment, recalling the raucous cheering and yells of support was helping me get through a decidedly less euphoric situation.

“Asha, come here and stir this dal, please, or the lentils will stick to the bottom of the pot. Quickly—

jaldi, jaldi

!” my Nani said impatiently. She bustled to the other side of our kitchen and checked on the apple-filled pastries Grandma Bee had placed on a cookie sheet in the oven.

“Blanca, these are turning brown,” Nani said, shooting a look across the kitchen at my dad’s mom, who was pulling a plate of deviled eggs out of the fridge.

Unlike the Sympathizers at the planning meeting, this was a crowd I dearly wished I could have avoided. Putting both sides of my family in the same house for a multiple-holiday Diwali-Christmas Festival of Insanity was too much to handle. Never mind that Diwali was long past and Christmas wasn’t here yet. With both grandmothers fighting for control of the kitchen prior to our annual mid-December dual-family blowout, there were clashing aromas competing for dominance, flour was everywhere, and there was a constant tug-of-war over the spice rack. As a kid I’d loved the excitement—and, of course, the presents. Now I kind of wished we were atheists.

“They shouldn’t be done yet, Geeta,” Grandma Bee insisted, her voice cutting across the household noise as Nani made as if to remove the pastries from the oven. “You must have overheated the oven when you were baking your, ah, chicken casserole. And

please

call me Bee. You know nobody’s called me Blanca in years.”

“Only if you’ll call it biryani,” Nani muttered peevishly under her breath.

“¡Ave María Purísima!”

Grandma Bee said, sighing. This was one of the rare occasions when she got so exasperated she resorted to Spanish. The rest of the time, it was strictly English Only. She even got uncomfortable when Nani spoke Hindi.

My fourteen-year-old cousin Christopher cowered at the kitchen table where he was tossing a fruit salad, and I hunched over the gigantic pot of dal on the stovetop and hoped I could make a quick escape. I’d rather be backstage. Or, preferably, not even in the building.

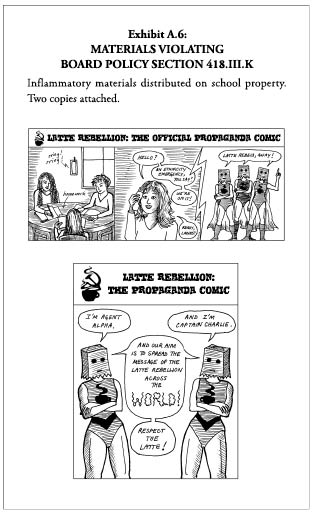

At the Latte Rebellion meeting I’d been officially backstage, sitting quietly at our table and trying not to attract too much attention as the first-ever lecture and rally were meticulously planned out. There was a short list of three potential speakers, and Maria McNally volunteered to hold an under-the-radar meeting at our high school to get the word out. We—Agent Alpha, Captain Charlie, and Lieutenant Bravo—had been put in charge of making propaganda-comic-style rally flyers, using Miranda’s genius artistic talent.

Weeks ago, Miranda had sketched out three superhero characters with paper bags over their heads and the Latte Rebellion logo on their spandex bodysuits. All three were mild-mannered and respectable young women by day, but were ready to throw on their Latte Rebellion outfits and jet out the door if they heard that a brown person somewhere was being oppressed. When we told Miranda how amazing her drawings were, she did a little happy dance because her list of prospective colleges included some prestigious art schools. None of us had heard anything from colleges yet, though, except for a few kids who did Early Decision.

If Robbins College had had an Early Decision option, I totally would have gone for it. I kept thinking about that School of Social Welfare and about Thad, right down the road at UC Berkeley. But I had to wait around like all the rest of the peasantry.

Christopher dropped the fruit salad spoon on the floor, somehow managing to send squishy bits of banana, orange, apple, and kiwi everywhere. In fear of the raging grandmas, he began to apologize pathetically. I winced and tried to ignore the sudden flood of solicitous, reassuring babble that ensued as both Nani and Grandma Blanca swooped in with paper towels.

It seemed fitting, somehow, that the thing to bring the bickering matriarchs of my family together would be a fruit salad. Not the weeks of meticulously planning out the big meal via emails back and forth, making sure to include favorite dishes from both the Indian-American side and the Mexican-Irish-American side of the family. Not the menu that included both biryani and Spanish-style rice, in addition to the mixed nuts, deviled eggs, and roasted turkey breast.

Nope, it was the plain old cobbled-together culturally neutral fruit salad. An out-of-control riot of flavors and colors tossed willy-nilly into a bowl (and, thanks to Christopher, partially onto the floor).

Yeah, that was my family, all right. A real riot. And I was caught up in it with no way out.

Truthfully, though, I was a little relieved to stay close to home and stop worrying about the Rebellion for a couple of days. There was a lot of pressure now that it

was

a club, and it was exhausting to have to keep track of it all—the meetings, the guest speaker—

and

make sure that our vacation was still possible. Every week, I transferred whatever money we’d made out of the online payment system and into the bank account I’d opened for our travel fund. It was something Carey had volunteered to do, but somehow I’d ended up doing this, too. Not only that, but most of our college applications were due at the end of December, and I had to scramble to get those finished in what little spare time I had left.

By the time the wrecking crew that was my extended family cleared out of the house and I felt like my Winter Break had officially started, all I had the energy to do was flop on the bed, ready to hibernate. Which was basically what I did: sleeping till ten every morning, watching daytime TV until the afternoon, and trying to go out as often as possible in the evenings so as to avoid my parents’ obsession with cable news shows.

The Wednesday after the family blowout event, I came inside after a long, chilly day of Christmas shopping with Miranda and Carey and found both of my parents sitting at the kitchen table, looking up at me

very

somberly. Dad was chewing absently on the end of a pen, which he only did when he was mega-stressed. He had his reading glasses on like he’d been working.

“What happened?” I asked. When they didn’t answer right away, I dropped into one of the cushioned wooden chairs. It had to be bad. I thought about the constant barrage of reports about the weak economy lately—the ones my parents kept watching ad nauseam—and started to get a horrible feeling. “Is everything okay?”

“Oh, Asha,” my mother said, shaking her head and looking down at a piece of paper in front of her. I leaned over to peer at it and felt the bottom drop out of my stomach. My semester report card. And it clearly wasn’t up to par.

“You went through my

mail

?” I said, stalling.

“Don’t avoid the subject,” my dad said, his voice flat. “We’re talking about your report card, not your personal mail. A report card that is not, by any stretch of the imagination, up to your usual standards.” He looked at me, and I squirmed in my seat.

“It’s only one semester,” I began desperately. “I have a lot of time to bring up my grades. Nobody looks at midterm results. It’s just been … senioritis,” I concluded, clenching my hands in my lap and hoping I sounded convincing. But I was in deep Titicaca.

In the long silence that followed, a bird tweeted cheerfully in the purple-leafed plum tree outside the kitchen window, as if to mock me.

“If this is ‘senioritis,’ then maybe you need some treatment,” my dad finally said, thick eyebrows drawn down in an ominous frown. I knew he wasn’t trying to be funny. “Right here it says you got a B-minus in Calculus. A B-minus! That’s almost a C.” I avoided his hard gaze. “Last quarter you got an A-minus in math. I don’t understand it. And your other grades … History, B; Biology, B-plus … what happened, Asha?”

“I got an A in English,” I pointed out. My voice trembled, but I tried to keep composure. It couldn’t be

that

bad. I’d done fine on my SATs and on my first quarter report card. This one set of grades didn’t really matter.

“Look at these comments, though,” my mother said, quietly but with worry in her voice. She slid a finger down the computer printout. “‘Student shows aptitude for this subject but does not put full effort into class assignments.’ You got that comment from three of your teachers! You’ve been spending all this time ‘studying’ with your friends, but maybe we need to rethink that arrangement.”

They’d said nearly the same thing back in eighth grade, the time Carey and I let Kaelyn (yes,

that

Kaelyn) convince us to ditch school and go to the mall—they weren’t sure my friends were a good influence, I’d behaved irresponsibly, I’d allowed peer pressure to get the better of me … the list of my faults went on and on. They were just

so disappointed.

My mother had said she felt responsible, and I knew she was afraid she’d made some critical mistake in raising me and this was the beginning of the end. She had the same look on her face now as she did then.

I bowed my head, cheeks flaming. “I guess we haven’t been studying very efficiently.” What could I say? There was nothing

to

say, unless I wanted to confess everything. Which I didn’t.

“We’re just concerned for you,” my dad said, his voice softening. “I realize it’s hard to keep going at the same pace when high school is almost over, but if you don’t maintain your effort, it

will

hurt your chances of getting into college. Your final grades matter, you know that. We just want you to get the success you deserve, honey, but you have to put the work into it.”

My dad segued into his favorite soliloquy about how he was a self-made man whose parents never went to college and never could have gotten as far as he did in life if he hadn’t worked hard every second of every day, blah blah blah. And my grandparents—on both sides—had worked so hard fighting against prejudice and ignorance. They would be so disappointed if they knew what had happened.

I tried not to roll my eyes. If my grandparents

really

knew what I’d been doing, with the Latte Rebellion … I wasn’t so sure they’d be disappointed.

I sighed and fiddled with the empty envelope stamped with the school letterhead. Part of me wanted to tell my parents everything, about how we’d had this bright idea about raising enough money to take a vacation next summer without having to waste valuable study time on anything so prosaic as a regular

job

. But I couldn’t. If I tried to explain, it would come out sounding all wrong. Just like every other time I tried to explain myself to them, it would end up being my fault anyway.

Dad’s lecture went on and on, the point essentially being that if I started hanging out with “troublemakers” and slacking off, I would ruin my life, eliminate any chances of going to college, and end up in a dead-end food service job for the rest of my life. Going into food service was the worst thing imaginable to my parents.

Meanwhile, my mother kept nervously wringing her hands and talking about how they wanted me to have every opportunity and that was why they wanted to nip whatever it was in the bud and put me back on the path to good study habits. I nodded and said “yes, Dad” and “no, Mom” at the right spots, trying not to scream from frustration.

Still, there was the mocking little voice in my head that kept insisting I should have listened to Carey. She’d kept telling me I needed to spend more time on Calculus, and I hadn’t wanted to hear it. Who would? But now I was paying the price.

It wasn’t the grades that bothered me so much; I knew I could bring them back up. It was the fact that, from this point on, I would be under major parental surveillance, which effectively put the kibosh on any Rebellion involvement. And that was exactly what happened. I couldn’t be alone in any room of the house for even half an hour before one of my parents came in—ostensibly to check if I needed a snack, or to rummage in a kitchen drawer, or to turn the living-room TV to some depressing program about bad stuff going on in the world that I couldn’t do anything about.

Despite that, I still managed to get away every so often to see Carey. It

was

Winter Break, after all. As long as I took textbooks with me—and presented neatly finished homework afterward—even my dad didn’t complain.

The final Friday of vacation, we had a mini New Year’s Eve party at Miranda’s house. Besides Carey and I, Leonard, Bridget, and Darla were there, sitting around in the cozy living room, drinking sodas and eating chips, and reminiscing about how the Latte Rebellion used to be such a small-time operation. Now it was more about working for a cause and following it through, do or die.

Even though I missed the old days, I couldn’t help feeling a little excited about that.

“Hey,” Leonard said. “I have to show you something.” He asked Miranda if he could use her computer to go online. We all crowded around the back of the office chair in the corner of her parents’ living room and watched as he surfed to the social networking site FriendSpot, easily the most popular website around school. He typed “Latte Rebellion” into the search box.