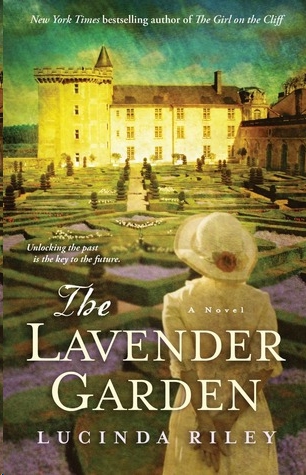

The Lavender Garden

Thank you for downloading this Atria Books eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Atria Books and Simon & Schuster.

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

For Olivia

What you are, you are by accident of birth; what I am, I am by myself.

—Ludwig van Beethoven

Unbroken night;

Darkness is the world I know.

Heavy burden;

No lights behind the window glow.

Softer day;

A hand reached out amidst the gloom.

Touching gently;

Spreading warmth across the room.

Twilight hours;

Shadows ebb and flow from you.

Secret longing;

Heart grows tender, beats anew.

Unbroken light;

Darkness was the world I knew.

Burning brightly;

Glowing with my love for you.

Sophia de la Martinières

July 1943

Gassin, South of France

Spring 1998

E

milie felt the pressure on her hand relax and looked down at her mother. As she watched, it seemed that, while Valérie’s soul departed her body, the pain that had contorted her features was disappearing too, enabling Emilie to look past the emaciated face and remember the beauty her mother had once possessed.

“She has left us,” murmured Phillipe, the doctor, pointlessly.

“Yes.”

Behind her, she heard the doctor muttering a prayer, but had no thought to join him in it. Instead, she stared down in morbid wonder at the sack of slowly graying flesh which was all that remained of the presence that had dominated her life for thirty years. Emilie instinctively wanted to prod her mother awake, because the transition from life to death—given the force of nature Valérie de la Martinières had been—was too much for her senses to accept.

She wasn’t sure how she should feel. After all, she had played this moment over in her head on many occasions in the past few weeks. Emilie turned away from her dead mother’s face and gazed out the window at the wisps of cloud suspended like uncooked meringues in the blue sky. Through the open window, she could hear the faint cry of a lark come to herald the spring.

Rising slowly, her legs stiff from the long nighttime hours she had been sitting vigil, she walked over to the window. The early-morning vista had none of the heaviness that the passing of the hours would eventually bring. Nature had painted a fresh picture as it did every dawn, the soft Provençal palette of umber, green, and azure gently ushering in the new day. Emilie gazed across the terrace and the formal gardens to the undulating vineyards that surrounded the house

and spread across the earth for as far as her eyes could see. The view was simply magnificent and had remained unchanged for centuries. Château de la Martinières had been her sanctuary as a child, a place of peace and safety; its tranquillity was indelibly printed into every synapse of her brain.

And now it was hers—though whether her mother had left anything behind from her financial excesses to continue to fund its upkeep, Emilie did not know.

“Mademoiselle Emilie, I’ll leave you alone so you may say goodbye.” The doctor’s voice broke into her thoughts. “I’ll take myself downstairs to fill out the necessary form. I am so very sorry.” He gave her a small bow and left the room.

Am I sorry . . . ?

The question flashed unbidden through Emilie’s mind. She walked back to the chair and sat down once more, trying to find answers to the many questions her mother’s death posed, wanting a resolution, to add and subtract the conflicting emotional columns to produce a definitive feeling. This was, of course, impossible. The woman who lay so pathetically still—so harmless to her now, yet such a confusing influence while she had lived—would always bring the discomfort of complexity.

Valérie had given her daughter life, she had fed and clothed her and provided a substantial roof over Emilie’s head. She had never beaten or abused her.

She simply had not noticed her.

Valérie had been—Emilie searched for the word—

disinterested.

Which had rendered her, as her daughter, invisible.

Emilie reached out her hand and put it on top of her mother’s.

“You didn’t see me, Maman . . . you didn’t see . . .”

Emilie was painfully aware that her birth had been a reluctant nod to the need to produce an heir for the de la Martinières line; a requirement contrived out of duty, not maternal desire for a child. And faced with an “heiress” rather than the requisite male, Valérie had been further disinterested. Too old to conceive again—Emilie had been born in the very last flush of her mother’s fertility at forty-three—Valérie had continued her life as one of Paris’s most charming, generous, and beautiful hostesses. Emilie’s birth and subsequent presence had

seemed to hold as much importance for Valérie as the acquisition of a further Chihuahua to add to the three she already owned. Like the dogs, Emilie was produced from the nursery and petted in company when it suited Maman to do so. At least the dogs had the comfort of one another, Emilie mused, whereas she had spent vast tracts of her childhood alone.

Nor had it helped that she’d inherited the de la Martinières features rather than the delicate, petite blondness of her mother’s Slavic ancestors. Emilie had been a stocky child, her olive skin and thick, mahogany hair—trimmed every six weeks into a bob, the fringe forming a heavy line above her dark eyebrows—a genetic gift from her father, Édouard.

“I look at you sometimes, my dear, and can hardly believe you are the child I gave birth to!” her mother would comment on one of her rare visits to the nursery on her way out to the opera. “But at least you have my eyes.”

Emilie wished sometimes she could tear the deep-blue orbs out of their sockets and replace them with her father’s beautiful hazel eyes. She didn’t think they fitted in her face, and besides, every time she looked through them into the mirror, she saw her mother.

It had often seemed to Emilie that she had been born without any gift her mother might value. Taken to ballet lessons at the age of three, Emilie found that her body refused to contort itself into the required positions. As the other little girls fluttered around the studio like butterflies, she struggled to find physical grace. Her small, wide feet enjoyed being planted firmly on the earth, and any attempt to separate them from it resulted in failure. Piano lessons had been equally unsuccessful, and as for singing, she was tone-deaf.

Neither did her body accommodate well the feminine dresses her mother insisted she wear if a soiree was taking place in the exquisite, rose-filled garden at the back of the Paris house—the setting for Valérie’s famous parties. Tucked away on a seat in the corner, Emilie would marvel at the elegant, charming, and beautiful woman floating between her guests with such gracious professionalism. During the many social occasions at the Paris house and then in the summer at the château in Gassin, Emilie would feel tongue-tied and uncomfortable. On top of everything else, it seemed she had not inherited her mother’s social ease.

Yet, to the outsider, it would have seemed she’d had everything. A fairy-tale childhood—living in a beautiful house in Paris, her family from a long line of French nobility stretching back centuries,

and

with the inherited wealth still intact after the war years—it was a scenario that many other young French girls could only dream of.

At least she’d had her beloved papa. Although no more attentive to her than Maman, due to his obsession with his ever-growing collection of rare books, which he kept at their château, when Emilie did manage to catch his attention, he gave her the love and affection she craved.

Papa had been sixty when she was born and died when she was fourteen. Time spent together had been rare, but Emilie had understood that much of her personality was derived from him. Édouard was quiet and thoughtful, preferring his books and the peace of the château to the constant flow of acquaintances Maman brought into their homes. Emilie had often pondered just how two such polar opposites had fallen in love in the first place. Yet Édouard seemed to adore his younger wife, made no complaint at her lavish lifestyle, even though he lived more frugally himself, and was proud of her beauty and popularity on the Paris social scene.

Often, when summer had come to an end and it was time for Valérie and Emilie to return to Paris, Emilie would beg her father to let her stay.

“Papa, I love it here in the countryside with you. There is a school in the village . . . I could go there and look after you, because you must be so lonely here at the château by yourself.”

Édouard would chuck her chin affectionately, but shake his head. “No, little one. As much as I love you, you must return to Paris to learn both your lessons and how to become a lady like your mother.”

“But, Papa, I don’t want to go back with Maman, I want to stay here, with you . . .”

And then, when she was thirteen . . . Emilie blinked away sudden tears, still unable to return to the moment when her mother’s disinterest had turned to neglect. She would suffer the consequences of it for the rest of her life.

“How

could

you not see or care what was happening to me, Maman? I was your daughter!”

A sudden flicker of one of Valérie’s eyes caused Emilie to jump

in fear that, in fact, Maman was still alive after all and had heard the words she had just spoken. Trained to know the signs, Emilie checked Valérie’s wrist for a pulse and found none. It was, of course, the last physical vestige of life as her muscles relaxed into death.

“Maman, I will try to forgive you. I will try to understand, but just now I cannot say whether I’m happy or sad that you are dead.” Emilie could feel her own breathing stiffening, a defense mechanism against the pain of speaking the words out loud. “I loved you so much, tried so hard to please you, to gain your love and attention, to feel . . .

worthy

as your daughter. My God! I did everything!” Emilie balled her hands into fists. “You were my

mother

!”

The sound of her own voice echoing across the vast bedroom shocked her into silence. She stared at the de la Martinières family crest, painted 250 years ago onto the majestic headboard. Fading now, the two wild boars locked in combat with the ubiquitous fleur-de-lis and the motto, “Victory Is All,” emblazoned below were barely legible.

She shivered suddenly, although the room was warm. The silence in the château was deafening. A house once filled with life was now an empty husk, housing only the past. She glanced down at the signet ring on the smallest finger of her right hand, depicting the family crest in miniature. She was the last surviving de la Martinières.