The Legend of Jesse Smoke (20 page)

Read The Legend of Jesse Smoke Online

Authors: Robert Bausch

“So who’ll fill in on running downs?” I asked.

“Alvin Parker,” Bayne said.

Parker had been our starter for the two years before. He was not a great player, but he played the run fairly well. He’d give Ruggins a battle at least on that side. He’d get in the tangle.

So we were talking about moving some players around. We were discussing the kind of defensive formations we would use to stop Oakland, and then in the middle of it, after a short pause, Bayne said, “What about the quarterback?”

I looked at him. Coach Engram said, “We’ll get to that.”

“What?” I said.

“Greg’s been telling me some things about that girly quarterback of yours.”

“Really. What about her?”

“He’s got some film he wants me to see,” said Engram.

“She plays the second-string offense against our first-string defense and beats them,” Bayne said. “They keep scoring on us, and she doesn’t miss.”

I couldn’t help feeling like I should jump up and hug the guy. “She won’t miss those long bombs down the sideline,” I said. “You give her time and she’ll pick apart any defense out there.”

“You think so,” Coach Engram said.

“And we wouldn’t be playing to any empty seats either,” I said, thinking again of what that might do to our job security. I’m sorry to say I was thinking about that, but … I was. I’d never seen Flores around practice so much, and Coach Engram himself had said a number of times, “This is it, folks. This is the year. We gotta do it.” I think we all knew what was at stake.

“Then we’re going to have to close practice,” Engram said.

I couldn’t contain my surprise or excitement. “Are you going to do what I think you’re going to do?”

“I don’t know. What I

do

know is I’m just tired of missing those open plays downfield.”

“So …”

“I’ll make the announcement on Saturday. Enough folks will know about it after that to fill the stadium.”

“You going to do it, then?” Bayne said.

Engram just sat there looking at him. I could see he didn’t want to commit to it, even then. But he wanted so badly to win. And those two bad balls Spivey threw were haunting him. He respected me, I knew that. And he believed in Greg Bayne. We were both telling him, as clearly as we knew how, that Jesse could do it.

What was he supposed to do?

I stopped Jesse outside the weight room early Monday morning, all excited to give her the news. Coach Engram let me have the honor—believe it or not, we did have a discussion about who would tell her. I figured she might just grab me around the neck and squeeze so hard I’d faint. That’s how I pictured it. I thought she might want me to pick her up and swing her around like a daughter at a wedding reception. All she did was smile a bit and look out at the playing field. “It’s going to be your team, Jesse,” I said, confused by the cool of her reaction.

“I know,” she said.

“You’re not nervous are you?”

She looked at me. “I just wish my father was alive.” And by god her eyes were shining with tears.

“I wish he was too,” I said and I reached for her.

But she pulled back, raising her hand up, gently. “No,” she said. “It’s all right.” The tears ran down that pretty freckled face now. “I

just never thought …” she trailed off, looking out over the practice field again. A few players came out of the locker room and trotted down the hill.

“

I

never thought I’d see this day, either,” I said, trying to finish what she’d started to say.

And that’s when she reached over, touched my jaw with the tips of her fingers, and whispered, “I have you to thank for all this.” It was the most womanly thing I’d ever heard her say or do with her football uniform on, her voice husky and sad and beautiful. I really did feel kind of fatherly toward her then, as I noticed how perfect her neck was—the small, fine bones under her throat produced exquisite shadows. Suddenly I was terrified for her.

“I want you to practice that quick release of yours, you hear?”

She nodded, taking her hand away.

“You don’t see something right away, throw the damned football into the crowd.”

“We’re talking game plan right now?”

I laughed a little. “And another thing, Jesse. You can’t tell anybody about this yet, all right? Coach Engram’s going to close practice. No one can know about this for a while.”

“What about Nate?”

“Not even him.”

“He said he might come to a practice this week.”

“He won’t be able to get in. They’ll be closed.”

She still had the tears running down her face. “Just Nate?”

“You can’t tell anyone,” I said, feeling bad. “Look, I’m sorry. He’ll know soon enough.”

She didn’t like it, but she wiped her eyes and turned to go into the weight room. “Anyway, thank you,” she said again.

“We’re going to make history, Jesse,” I said, but I don’t even think she heard me. She was already through the door.

In spite of my anxiety over her continuing good health, I really was excited about giving Jesse the ball. For one thing, she would be

working a lot more with me now. We’d work on the game plan together and be in meetings most of every evening after practice. We’d watch film of the Oakland defense together. She’d have to learn every move they made, every nuance of their defensive alignments.

She already knew our playbook as well as anyone, myself included. She’d memorized every single facet of our offense. I could talk to her about specific plays and she didn’t need the playbook in her lap to page through it and find what I was talking about. Even Ambrose had to do that once in a while. And Spivey hardly ever went anywhere without his playbook.

Jesse had the damn thing in her head.

We clicked from day one. I think I learned more about my own plays from her than I had in almost a decade of coaching. I’m not just saying that.

As he said he would, Engram closed practice that week. (Roddy was livid, but he wrote stories about a strategy that might save the season. “This team is at a crossroads,” he said.) The players themselves all got behind Jesse, and the offense looked really crisp. We worked on the running game, but there were a few good passing plays sprinkled in. The whole line worked to keep Jesse on her feet. We even ran a few plays against our own defense, promising $200 bonuses to the defensive guy who could lay a hand on Jesse before she let go of the ball. Nobody got to her. Even Mickens blocked his ass off, and he never did like to do much of that. It got to be a matter of honor on the part of the offensive guys: They really wanted to keep Jesse from being hit.

Of course, all of them knew it was a virtual impossibility to keep the quarterback from getting knocked down once in a while. But Coach Engram is wonderful at motivating people. One day he got the offense together and showed films of the greatest offensive line the Redskins ever fielded. And it wasn’t that early group of “Hogs” that

won those eighties championships, either. The 1991 offensive line allowed just 8 sacks in fifteen games. In the last game, playing in a meaningless contest, they gave up a ninth, but their quarterback that year, Mark Rypien, was as well protected as any quarterback ever was. Engram made it a matter of pride for the whole offense, and Dan Wilber made sure every man on the line knew and understood what they were going for. They were going to be better than that 1991 line.

On the whole, I was happy with how the practices went. So was Engram. He came up to me on Thursday, late in the afternoon, when we were just finishing two-minute drills. “I gotta tell you,” he said, grinning, “she looks good.”

“Reminds me of you.”

“More like a young Tom Brady.”

“She stands like him sometimes, but you know when she drops back in the pocket, she actually looks like Griese. You ever see film of him?”

“Really solid footwork. Like she’s dancing on air.”

“Did you ever think you’d see such a thing? That young woman can throw it as hard as Brett Favre did.”

“A woman,” he said, shaking his head. “Wait’ll I make

that

announcement.”

“Look, we’ve all seen women play basketball as good as any man.”

“Spivey’s fit to be tied,” he said, a slight change in his tone.

“Didn’t think he’d be happy about it.”

“He’s trying to be a mensch. He likes her. They’re friends.”

“Really?” I said. “I hadn’t noticed.”

“No, they’re friends.

Says

he’s glad for her.”

“He knows he can play. He’ll be ready.”

“It embarrasses him. He’s ‘humiliated beyond measure,’ is how he put it.”

“Who’d he say that to?” I asked.

“Charley Duncan.

He

thinks it’s pretty silly too.”

“Duncan’s the first general manager to sign a woman,” I said. “He should be happy to know he’s going down in history.”

“It’s the ‘going down’ part I expect he’s worried about. Maybe on some level we all are.”

I said nothing for a while, then I gave a short laugh. “I guess it

is

kind of humiliating. I wouldn’t want to get beat out by …” I didn’t finish the sentence. “What about Ambrose?”

“I don’t know. I put him on the unable to perform list this morning. He’s out of it, in any case.”

“I feel kind of sorry for him.”

Engram shook his head, chuckling to himself. “Man, either I’m delusional and on the verge of being fired or we’re about to chart a whole new territory.”

“It’s new territory, that’s for damn sure, no matter

what

happens to you or me. Calling it ‘new territory’ may be a vast understatement of what we’re about to do.”

“You got that right.”

We both stood there a while, thinking. Then he said, “Let’s go have a cigar and talk about how we make the announcement.”

Saturday morning at his regular pregame press conference, Coach Engram told the press. What he said was, “I’m making a change at quarterback. All my coaching life I’ve tried to emphasize that I am always looking for the best player at every position. I have played quarterback in this league, I know what is required, and I am certain that we can improve the play at that position. So I’m going to give Jesse Smoke a shot at it before this season starts to get away from us.”

Well, you remember the pandemonium that followed. The whole country seemed to ignite with the news. We were in every newscast, every newspaper, every online news feed. Jesse’s face and mine and Coach Engram’s instantly plastered all over the world. Almost nobody had ever seen her play quarterback. So maybe it shouldn’t have been surprising that what the sportswriters of America wanted to know was: Had Coach Engram lost his mind? Some said it was “a give-up

move,” that the coach was saying good-bye to the season as flamboyantly as he could. Some said it was simply a novelty move to fill the stadium, that she’d be benched after the first series. Others claimed it was an affront to the league and the league office, a deliberate attempt to humiliate the commissioner. It was no big deal to let a rookie kick field goals for you, and nothing new about starting a rookie quarterback, even in the middle of a season. But when that rookie happens to be a female? You’d have thought we’d announced that the president of the United States was going to start at quarterback.

The Raiders came to town Saturday, and most of them said they didn’t care

who

played quarterback for us. Delbert Coleman, who the Steelers had traded to the Raiders at the beginning of the season, said he was looking forward to the game. He was asked, “Do you feel as though you have a score to settle with Jesse Smoke for the way she hit you in the face with the ball back in training camp with the Steelers?”

He still had a Band-Aid across his nose. “Yeah,” he said. “I feel like I got a score to settle. But I don’t really believe they’ll play a woman. I promise you this, though: Whoever’s at quarterback, I’m going to put

him

or

her

on the seat of

his

or

her

pants.” Most of the Raiders were confident, and quietly respectful—they did not make fun of us the way some of the media did—and they were ready to play.

It rained on game day, water dropping out of the sky like it was being poured from a watering can. Even so, every seat in the stadium had an ass in it. And they sold 2,000 standing room only tickets as well. You couldn’t find an empty space to move around in. More than 96,000 people waited for the kickoff, in an atmosphere of expectation the likes of which you’ve never seen, outside of a rock concert, say—or a public hanging.

As in every game up to that point I called plays from a booth upstairs, the best seats in the house. Jesse could hear me and Coach Engram through a headset in her helmet. Our game plan was to run as much as possible to keep the ball away from the Raiders’ offense. We won the toss and after the Raiders kicked off, we got it out to the 25-yard line.

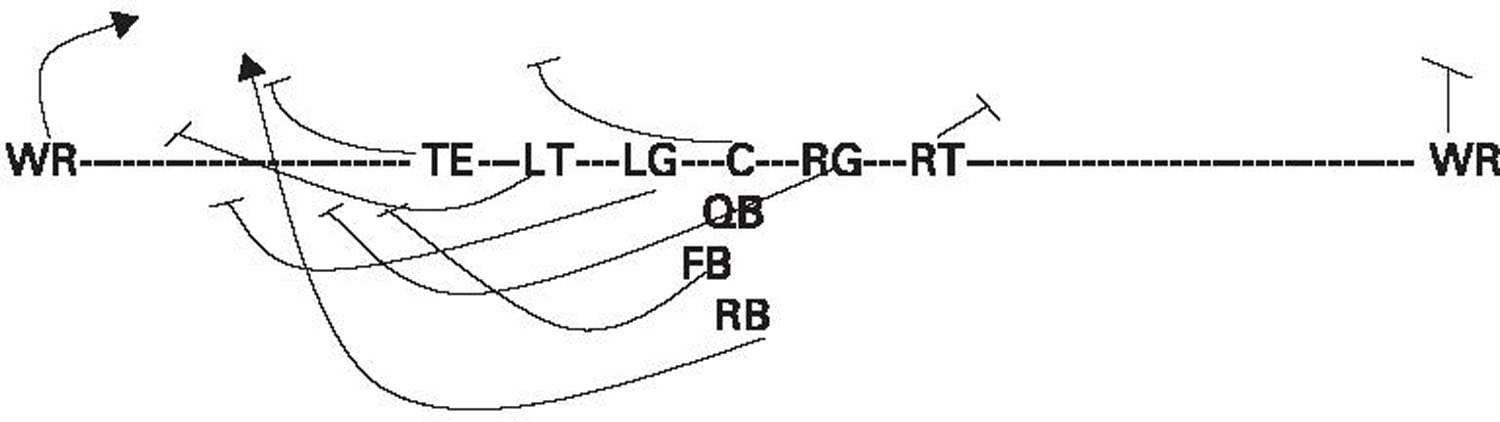

On the first play from scrimmage, Jesse gave the ball to Walter Mickens and he ran off tackle for 6 yards. When he got back to the huddle, he was muddy and soaked. On the next play I called a sweep around the left end. It’s one of the oldest plays in all of football, and also one of the most basic. Vince Lombardi called it 49 28, and it came to be known as the Green Bay Sweep. It was designed for the running back to “run to daylight.” It looks like this: