The Legend of Sheba: Rise of a Queen (41 page)

Read The Legend of Sheba: Rise of a Queen Online

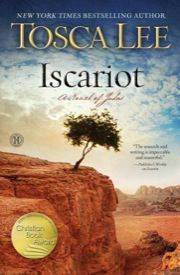

Authors: Tosca Lee

According to the Quran, the queen was a worshipper of the sun. Shams, the sun goddess, was known and worshipped in ancient Yemen along with a host of other gods, depending on where one lived. The god Almaqah is widespread in surviving texts, and ruins of ibex-adorned temples dot the Sabaean territory. Scholars, however, do not agree on whether Almaqah was a lunar or solar deity.

Though we are given far more about the life of King Solomon (who reigned roughly 970-930 BC by most chronologies) than of Sheba’s queen, he wears a slightly different face in each of the three major accounts that mention him. In the Bible, he is the all-wise king who ultimately failed to follow the dictates of Yaweh—who granted him the knowledge he asked for and the riches and power he did not. In the Quran, he speaks the language of animals and even insects, learns about Sheba’s queen from the curious hoopoe bird, and commands jinns to deliver her throne to him before her

arrival. Arabic legend says he forced her to reveal the true nature of her feet with a pool of water in his throne room.

In the

Kebra Nagast

, he is the wily king who resorts to trickery again—this time to persuade the queen to sleep with him. He later loses the Ark of the Covenant to the Judean honor guard he sends home with Menelik after his son’s visit. According to lore, Solomon only intended to send a copy of the ark with Menelik so that he might worship Yaweh in his faraway home. But Menelik, concerned about Solomon’s growing apostasy, has the guard smuggle the true ark out of Jerusalem, leaving the forgery in its place. Today many Beta Israel “Black Jews” of Ethiopia claim lineage from Menelik’s Israelite cohort. (Others claim descent from the ancient tribe of Dan.)

Though evidence of a royal city near Jerusalem’s Temple Mount and other buildings dating to the time of Solomon confirm biblical references to his projects, many scholars dispute the claims of Solomon’s wealth and influence as inflated.

And so we turn from here to that mystical third player in this drama: the ark.

The idea of an ark as a battle standard is not unique to Israel. The

markab

served a similar purpose in wartime, though to my knowledge was never infused with the spiritual power of Israel’s Ark of the Covenant—a veritable weapon of mass destruction. Gold chests containing sacred objects occur throughout ancient history. (Such a processional chest discovered in Tutankhamen’s tomb elicited a flurry of sensationalism in 1922. The dimensions for the pylon-shaped chest, however, were not the same as those for the Ark of the Covenant, and Tutankhamen’s “ark” bore the likeness of Anubis.)

What really happened to the Ark of the Covenant has been the subject of countless searches, legends, conspiracy theories—and of course Hollywood movies—ranging from locations in Israel, Egypt,

Arabia, Ireland, France, and even the U.S. by more than a few Indiana Jones look-alikes.

The obvious answer is that the ark was taken by Nebuchadnezzar in his 587 BC siege of Jerusalem. The ark, however, is not mentioned among the list of goods seized from the temple in 2 Kings 25:13–15 or Jeremiah 52:17–22—a list that details items taken from the temple columns and bronze sea cauldron, down to shovels, dishes, and wick-trimmers. Only the apocryphal 4 Ezra 10:19–22 mentions the plundering of the ark—a book generally thought to have been written 90-100 AD and in response to Roman invasion. I find it incredible that Jeremiah, the “Weeping Prophet,” would fail to mourn the capture of the ark in his musings. Nor is the ark listed in the items returned by Cyrus to Israel in the Book of Ezra.

According to 2 Maccabees, Jeremiah buried the ark in a cave on Mount Nebo just east of Jerusalem prior to the invasion, keeping it “until the time that God should gather His people again together.” In

The Lost Ark of the Covenant

(2008), Tudor Parfitt postulates it was later removed from Israel to Yemen.

Most interesting to me for the purpose of this book is the tradition of the ark and ark replicas in Ethiopia. Every Ethiopian Orthodox Church keeps a

tabot

—a stone slab representing the tablets of the ark or a replica of the ark itself. Without a

tabot

, the church is not considered consecrated. That said, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church also claims to have the real thing. Ask the guardian of the ark—a monk of no other name committed to the lifelong office of tending the holy relic in secret—at the Chapel of the Tablet in Aksum and he will attest that the ark is under his protection. The only downside is that he’s the only one allowed to see it.

Given the tradition of ark replicas, one “conspiracy” theory caught my eye in particular—an idea based on the peculiar attention given to the length of the ark’s poles when it was installed in

the temple (2 Chronicles 5:9). Also, according to 1 Kings 8:9 and 2 Chronicles 5:10, there was “nothing in the ark” other than the two stone tablets of Moses, excluding mention of the jar of manna and Aaron’s budded staff. The theory here being that a fake with much longer poles was installed in the temple and the true ark hidden, ostensibly, for safe-keeping.

Others believe the ark still resides in Jerusalem and that all questions will be answered the day the mount is better excavated—which may be very long in coming due to the extreme sensitivity of the site where the Dome of the Rock sits today. That said, the Temple Mount Sifting Project, dedicated to excavating the debris of a hole dug (to great criticism) into the temple platform in 1996-1999 to build the El-Marwani Mosque, has unearthed some spectacular finds in the 20 percent of rubble sifted so far. You can follow the progress of the project at: templemount.wordpress.com.

Jerusalem is rife with underground tunnels, including the one by which David famously took the city (possibly discovered in 2008 by Dr. Eilat Mazar), and a tunnel system adjacent to the Western Wall. No doubt many more tunnels lay hidden beneath the Temple Mount.

A couple of additional notes:

1. I’ve no doubt committed a cultural sin in eliminating the aleph (’) and other notations from Sabaean proper nouns in order to spare readers (and myself) names such as Amm’amar, Ma’d

karib, dh

t-Ba’dån.

2. Bilqis’ “fearless or reckless” ibex urn is imagined, though the statue of Astarte with the wax plugs in her breasts is based on a figurine of the goddess discovered in Tutugi, Spain, that dates to the sixth or seventh century and performs the same “miracle.” Religious machinations were not unknown in the ancient world—and about to get more common.

In the end, even though Solomon and the queen of Sheba have yet to show themselves in the archaeological record, they are as vividly alive as though their palaces still stand to the Ethiopians who claim the queen of Sheba as a vital part of their national identity and to Christians, Jews, and Muslims, for whom the veracity of David and Solomon’s unified kingdom underpins the unfolding story of their faith.

As for me, I assert that we don’t need artifacts to know something of either monarch: their questions, foibles, hurts, joys, triumphs, and losses are not unique—they are, in fact, the same as our own . . . if only with a little more gold.

* Other sources that proved invaluable to me:

Queen of Sheba: Treasures From Ancient Yemen

,

edited by St. John Simpson (Trustees of the British Museum, 2002)

Sheba: Through the Desert in Search of the Legendary Queen

, Nicholas Clapp (Nicholas Clapp, 2001)

Ancient South Arabia: From the Queen of Sheba to the Advent of Islam

,

Klaus Schippmann (Markus Wiener Publishers, 2001)

Arabia Felix: From the Time of the Queen of Sheba

,

Jean-François Breton (University of Notre Dame Press, 1999)

Arabia and the Arabs: From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam

, Robert G. Hoyland (Routledge, 2001)

Solomon & Sheba: Inner Marriage and Individuation

,

Barbara Black Koltuv (Nicolas-Hays, Inc., 1993)

Arabian Sands

,

Wilfred Thesiger (Penguin, 2007)

Of additional interest:

From Eden to Exile: The Epic History of the People of the Bible,

David Rohl

(Arrow Books, 2003)

The Sign and the Seal: The Quest for the Lost Ark of the Covenant,

Graham Hancock

(Arrow Books, 1997)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

E

very book is a journey of a thousand thank-yous and amazing companions—those who plan the route, travel alongside us, come to our aid, direct and encourage . . . and then, miraculously, do it all again.

Thank you to my readers for your intrepid souls, your encouragement, your bacon anecdotes, and for keeping me company through my marathon sprees. Every book is for you.

The pathfinders: Dan Raines and Meredith Smith of Creative Trust, who have yet to (visibly) flinch at my next harebrained idea. Jeanie Kaserman, who reads print so fine it cannot be seen by the naked eye.

My editor, Becky Nesbitt, and assistant editor, Amanda Demastus, who carve beauty from the storm of my early drafts. Jonathan Merkh, Rob Birkhead, Brandi Lewis, Jennifer Smith, Bonnie MacIsaac, Chris Long, Bruce Gore, and the entire team at Howard, thank you for your excellence.

Cindy Conger, who keeps me on track and sane. Mark Dahmke, who helped me search the ancient sky. Meredith Efken, who plodded through the early stages with me over Korean tacos. Stephen Parolini, who ran alongside me through the first draft with off-handed

Star Wars

references—your hilarity keeps me from hating you for your brilliance.

The experts: Dallas Baptist University professor of Old Testament Dr. Joe Cathey, who never exhausts of my myriad weird questions. Professor of history at the University of Northern Iowa Dr. Robert L. Dise Jr., Pastor Jeff Scheich, and new friend Jon Culver—thank you for lending your experience, intellect, and time.

Thank you to my family, genetic and adopted, for not assuming me dead in my long periods of silence and giving my stuff away, friends for never pointing out that I’ve been wearing the same thing for days, Julie for playing hooky with me the last thirty years, and Bryan, Wynter, Kayl, Gage, and Kole for sowing love in this heart.

Greatest thanks of all to the God I used to say shows me great things, but these days just mostly freaks me out with stuff I never saw coming. I’ve learned to quit saying “I’m ready,” because I never am.

Also by Tosca Lee