The Legend of Tyoga Weathersby (2 page)

The children of these homesteaders created a bi-lingual culture that bridged the chasm between two colliding worlds. They were at home in the villages of the Native Americans who accepted the children of their white neighbors as their own. They became increasingly less comfortable in the white world of religious intolerance, societal taboos and ever stringent government authority and control.

Tyoga Weathersby was a child of the frontier. His experience was shared mainly by the white orphans adopted by Native Americans. He ran naked and free through the Appalachians with his Ani-Unwiya brothers and sisters, and spoke Tsalagie with a better command than that of his native language.

Just a word about the Cherokee language, and the way that dialogue is used throughout the book: Tsalagie, the language spoken by the Cherokee Nation is a complex language. There was no way to transmit thought through the written word until Sequoyha invented the Cherokee alphabet in the early 1800s. The translation of the sounds from the Tsalagie to the English alphabet makes pronunciation of the words nearly impossible. How do you say “U-gv?” So, I created a pseudo-Tsalagie. Yep, I pretty much made up the words. Where possible, I based the sentence structure on the Tsalagie dialect, I placed the translation of the words in parenthesis after the Tsalagie in some places. In other places, I have not put any translation because – and this is the really neat thing - whatever English words you wish the Tsalagie to mean will work just fine!

Here’s a quick example: There is a scene when Tyoga’s nemesis, Seven Arrows, shows up unexpectedly and he asks Tyoga, “So, where is the wolf now?”

Tyoga replies, “He is here Skunulka.”

You can make that mean whatever you want it to mean. “He’s here, you Jackass,” works just fine; as does “He’s right here, you slimey bastard,”, or … well, you get the point. There will be places where the meaning of the pseudo-Tsalagie isn’t as obvious, but the story is constructed so that almost anything you decide the character says will work.

With all of this said, allow me, dear reader, to proclaim with unapologetic bravado, (and this is going to require some capitalization) I MADE THIS STORY UP. Yes, my friends, while some of the story is based upon historical fact, ie. Openchanecanough was the brother of Powhatan and was the Chief of the Powhatan Confederation when he ordered the massacre of 1622. But was he rescued by Tyoga’s grandfather?

Naahhhh. Made that up.

The mystic connection between the spirit of the wolf and Tyoga Weathersby’s soul is the critical twist that perhaps defines a new genre, for it most certainly is not historical fiction. If the reader is in any way offended by the characterizations or portrayals depicted in this book, here’s an idea: stop reading it and donate your copy to the local library.

The Legend of Tyoga Weathersby

is an exciting story, meant to do nothing more than entertain.

It was a joy to write. I hope it is as much fun to read.

The Legend

of

Tyoga Weathersby

Prologue

The Awakening - 1688

R

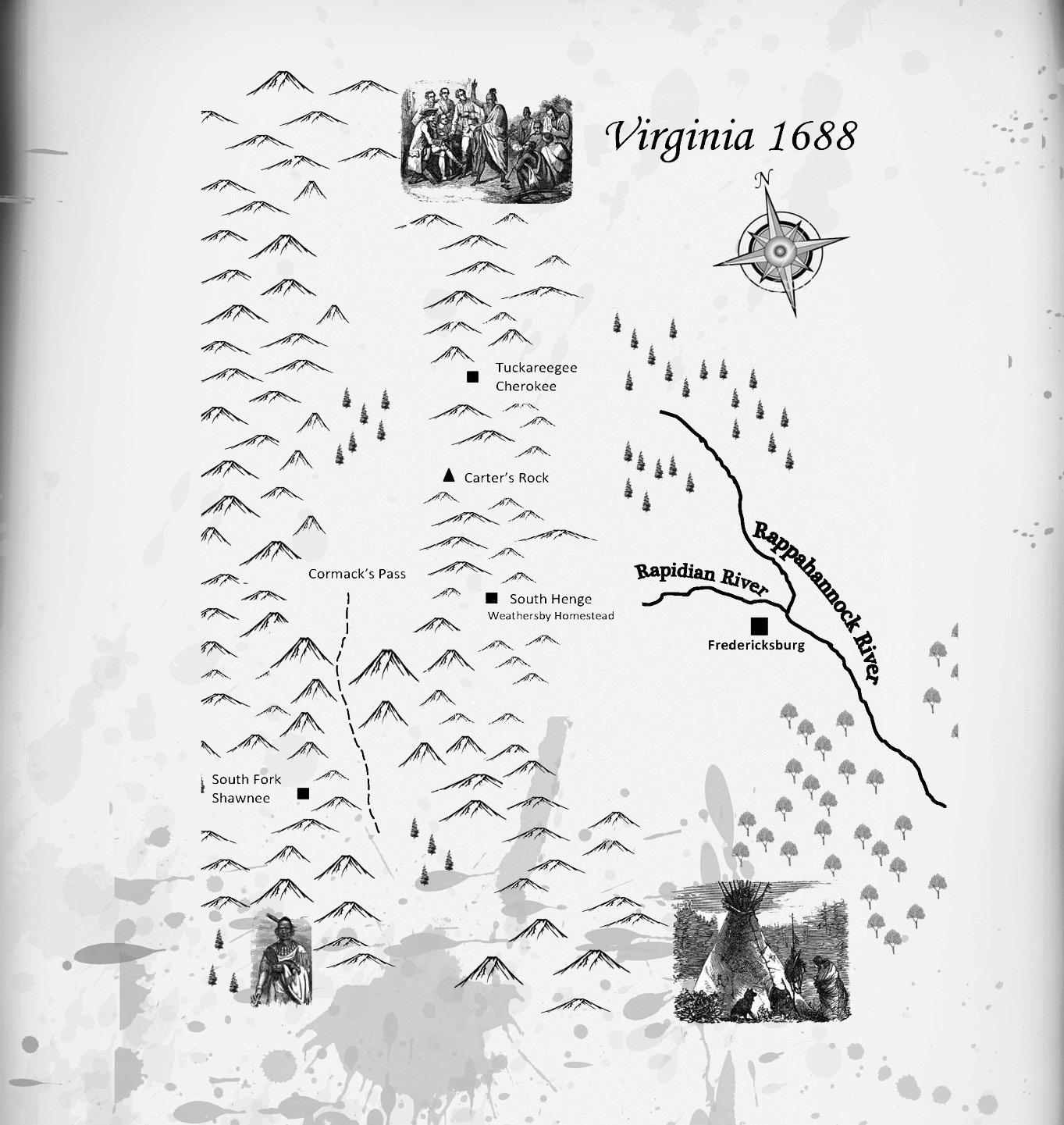

iveted by the morning mist that cloaks the Appalachians in the mysteries of time, distance, and space, Tyoga Weathersby stood by his papa’s side in the pre-dawn silence atop Carter’s Rock. Even at six years of age, his love of all things wild and free drew him to the openness of the mountains, plains, and valleys of the Blue Ridge with a siren’s call that simply wouldn’t be denied.

His papa, Thomas, understood. He had been the same.

Recognizing at an early age that Tyoga was different, Thomas nurtured his son’s adventuresome spirit and allowed him the freedom to range and roam far beyond the means of such a young lad. Untethered by the restrictions placed upon others his age, Tyoga experienced the wild with an intuitive sensing that was known only to those who were open to the awakening. He felt the rhythms of time and perceived the silent cues that filled the ether of the Appalachians with an unsettling welcome and shrouded intrigue.

Carter’s Rock was a simple granite outcropping about two-thirds of the way up the Appalachian peak that the Cherokee called Teshtahey. A two-hundred-year-old giant oak tree stood alone just to the southwest of the Rock, and marked the spot where well worn mountain paths converged before disappearing into the bottomless bog of unnamed hollers. The hard-packed trails bore silent witness to the bare feet of stone-age hunter/gatherers, the mocassined soles of Appalachian tribes who called themselves nothing more descriptive than “The People”; and, most recently, the boot heels of mountain men, fur trappers and pioneers.

Carrying his son on his back like a papoose, Thomas had been bringing Tyoga to the Rock since he was a newborn. Leaning his cradle board against the giant oak, he would sit in silence with his son at his side for hours on end. As Tyoga grew, they visited the Rock together many times. Usually they would do no more than listen to the wind and watch the eagles soar. Every so often, Thomas would turn to his son and say, “One day, Tyoga, you will know how to listen to the whispers in the wind. The eagles will speak to you and you will know the secrets of the rain. The strength of the wolf will flow through your veins, and the courage of the bear will steel your resolve. Stay true to the beating of your heart. The promise is in you. It will always show you the way. You have only to be awakened to its gifts.”

Tyoga heard these words often standing here on Carter’s Rock, but he had never understood their meaning. He knew that it was important for him to listen to the words, but he was growing impatient with watching the sun rise on countless mornings and listening to the same endless story about some “promise” that seemed to never come.

Today, the rising of the sun would be like no other.

It was June 21st. The occasion of the summer solstice. The longest day of year. The rising of the sun marked not only the beginning of a new day, but also the passage of time and the dawning of a new cycle of life. For a millennia, mankind had marked the perfect balance of darkness and light by celebration and sacrifice.

On this day, the blinding beams of light would bestow a gift that would change Tyoga’s life forever. The celebration of the gift would be his to determine. The sacrifice, his to bear.

The outline of the mountain range creasing the east rim of the Shenandoah Valley pierced the darkness as the rising sun pushed its silhouette forward to softly shadow the world awakening before them. With the innocence of childhood that permits inquiry without context, Tyoga broke the silence of the magical moment by asking, “Papa, do you ever hear things?”

The hint of a smile pulled at the corners of his father’s lips when he replied, “What do you mean ‘hear things’, son?”

“I don’t rightly know, papa,” Tyoga replied. “Sometimes I just hear things.”

Thomas knew that his very young son was ill-equipped to explain any further. But it was the sign that he had been waiting for all of Tyoga’s life.

“Yes, son. I do hear things.” He turned his gaze toward Craggy Gap far off in the distance. “I started hearing things when I was about your age.”

He paused as his mind’s eye took him back to the scene of a little sandy-haired boy standing next to his father about thirty-five years earlier. The smile changed from pride to resignation because what was about to happen to his son would change his life forever. He turned and looked at his boy for the last time—as he was—an innocent child of six. After the awakening, he would be innocent no more. He would know. With a deep sigh, he let the journey begin.

“More than just hearing, Tyoga, I understand,” he finished his reply.

“But, Papa, what do you hear? What is it that you understand?” Tyoga asked.

“I’ve been waitin’ for you to ask boy,” he said with a smile. “I reckon you’re ready now.” He placed his massive hand upon his son’s bony shoulder, and looked down into his tiny, freckled face. The awakening would be difficult for his young son to understand, so he tried to find words to prepare him for what was about to be.

“Son, nature …” he stopped.

Too big, too much.

He held his arm out and waved it slowly over the vista that surrounded them from horizon to horizon and said, “Tyoga, all men used to be able to hear the silent words that nature speaks. Her message helped them understand how all of this works, and where they fit into her plans. But somewhere along the way, most men have lost the gift to listen, hear and understand. But Weathersby men, all the way back to your grandfather Joshia, have been awakened to the promise. We have been given the gift to understand that all of us are one with nature, noless privileged in her ways than the bear, beaver, fox or squirrel, and …” He stopped.

Still too much.

He took a deep breath, and simply said, “Ya know how before it rains, the birds quiet down and go to roost in the trees; Hester lies down in her stall; and the rabbits and squirrels hole up?” He looked deep into his son’s eyes to see if his words were making any sense. He couldn’t tell if he understood, but Tyoga was listening intently. Before he could start again, Tyoga’s eyes lit up and he said, “Papa, I know when it’s gonna rain, too.”

He smiled gently at his son’s lively, inquisitive eyes, and said, “I know you do, son. But there is so much more.”

Knowing that he could not explain it any better than that, he turned his son to face the east, and said, “It’s time. Face the gap. Close yer eyes. An’ wait.”

“Wait fer what, papa?”

“You’ll know. Hush now. Be still. You’ll know.”

Tyoga closed his eyes and faced Craggy Gap. The sun hadn’t risen and the chill of the morning air made him shiver. He stood there on Carter’s Rock soldier-straight, frightened at the vulnerability of standing with his back to the woods, eyes closed, guard down; for even at this tender age he was wary of recklessness and the dangers hidden in the shadows of early dawn. His papa’s hand resting on his shoulder secured their safety, and quieted the alarms sounding in his head. His slow, deep breathing lulled his spirit into acceptance and serenity.

Slowly—ever so slowly the awakening began.

A pinpoint of light cleaved the divide at Craggy Gap and in an instant exploded into the magnificence of a new day. The first rays of morning light were released like thunderbolts crashing against his freezing cheeks.

His head began to spin wildly as his tiny body was enveloped in the cloak of newness and warmth. The blinding beams of light that herald the sun’s perpetual rebirth cocooned his spirit and filled his soul with the harmony of being. He had been called to share in the mystery of oneness with mother earth.

This was his moment.

His spirit broke free of its earthly bonds and soared in weightless oneness with the beams of the rising sun. All that was malevolent in the primal forest was illuminated and cast aglow with the brilliance of the dazzling light. Sounds became sight, scents could be tasted, distance could be felt and time simply dissolved. The ancient mysteries locked deep within the very bowels of Mother Earth—secrets of the natural world understood only in the truth of their being—disclosed themselves to him as unembellished natural law. Secrets revealed only to those who have been granted the wisdom to not only listen—but to hear and understand—were passed on to yet another Weathersby.

He was startled at the revelations, and frightened at the savage rawness of the natural world. He began to open his eyes and turn to speak when he felt the heaviness of his papa’s guiding hand. “Keep yer eyes closed. Listen. Listen and hear the promise,” he heard his papa’s voice as if coming from a great distance away. “Do ya see, Tyoga? Do you understand? Is it tellin’ ya? Can ya hear? Are ya listenin’, boy?”

Time seemed to stop for young Tyoga. He stood stone still for a long time. He did not want the soaring to stop, but as the sun rose fully over the Gap, he was settling back into himself and permitted to rejoin his world—forever changed.

He did not open his eyes, but furrowed his brow trying to make sense out of what had just happened.

The mysteries revealed made no sense. How could so much beauty mask such horrific brutality? How could majesty and gentleness exist in the midst of such depravity and coarseness? How could the discordant extremes of love and hate, good and evil, right and wrong be permitted to confound the life of man, yet remain completely devoid of context and attribute for the rest of the natural world? Is the chasm between man and beast so profound that reconciliation is impossible, or is the veneer separating the two so thin that the difference does not really exist at all?

The velvet touch of his papa’s gentle hand upon his forehead released the worried wrinkles and allowed him once again to hear. He heard his Papa’s voice, this time very close to him say, “Tyoga. When you open your eyes it will be as if you are experiencing the world for the very first time. Don’t be afraid. From this moment on, you’ll be one with the trees and the air and the sun. The eagle will guide you. The raven will settle you. The whisper of the wind will prepare you. You will never know fear again. Your courage will inspire your friends and frighten your enemies.

“But, my son, your journey has only begun. The gift of the promise allows you to hear, but understanding its message will require more. You will be tested by the very power that has awakened you. But beware the victory. For in the spoils lie both a blessing and a curse. The choice you make will set your course for the rest of your life. I hope that you choose mercy. I pray that the price exacted for your kindness is less than the loss of your soul.”

Thomas looked down at his young son and noticed the difference. He felt the tears filling his eyes, and looked off into the distance.

Patting his son on the shoulder, he added, “All things happen only as they must. There is no right or wrong in the doing, it is only in the outcome that these things are marked. Be strong, my son. Now open your eyes.”

Tyoga opened his eyes and slowly surveyed his surroundings from horizon to horizon.

“Papa, I know.”

Part One

1694

The Legend is Born

Chapter 1

Trapped

I

t was a beautiful autumn day. The mountain sky was deep azure blue. The valley breeze carried the scent of the harvest and the sounds of the forest creatures preparing for the lean winter months ahead. Black bears were gorging themselves on the last of the blueberries and wild huckleberries that grew along the mountain trails. Enormous sunflowers, their gigantic yellow-wreathed heads bowed in acknowledgment of unheard applause, were alive with the cackle of ravens and jays as they feasted upon the bursting seedpod. The beavers were felling ash and elm to reinforce their sturdy dams, and stockpiling succulent birch branches in their underwater pantries. Scouting the hollows of Appalachia, she-wolves searched for a deep burrow in which they and their cubs could survive the brutal forces of the mountaintop winters.

In the late 1600s, the peaks of the Appalachain Mountains and the dark glades of the Shenandoah Valley were still the frontier wilderness. Little was known about the land west of the Mississippi River. The remarkable expedition of Lewis and Clark would not happen until the end of the century. Only the hardiest mountain men braved the unknown dangers of hidden mountain passes.

The pristine land was rich with the gift of life, and bursting with the promise of renewal anchored in the permanence of granite, quartz, and pyrites. The rivers and streams etched the land with serpentine runs of sparkling clarity. Thunderous waterfalls flooded cavernous gorges, and lacey traces carved their delicate patterns on moss-covered canvases of marbled slate. The forests were filled with the majestic canopies of five-hundred-year-old chestnut trees with their enormous boughs rising to the heavens in joyous celebration of the life they nourished and sheltered below. Ancient pines, birch, cedar, elm, maple, walnut and hickory carpeted the undulating landscape for as far as the eye could see.

The ridges of the Appalachains obscured the valleys below like ocean waves hiding their shadowing troughs. The cool air rising from their depths on a leeward ridge was the only hint of their existence. The air was crisp, clean, and clear.

There was no sound. The silence was broken only by the whisper of the wind in the pines, the murmur of cascading mountain streams, and the bark of frolicking squirrels. From floor to canopy, songbirds filled the ancient forests. Perched high above the forest floor, their incessant chatter pronounced judgment upon the happenings below. The plaintive cry of a lone wolf would echo unabated along the mountain’s spine and careen off the granite valley wall until absorbed in the depth of primal indifference.

Such was the world known to Tyoga and his Native American brother, Tes Qua Ta Wa.

Tyoga had grown up as a living bridge connecting two disparate cultures. His family had settled in a savage and raw land. He had been given the rare gift of living among the Indians who had accepted him—and the Weathersby family—as members of their tribe.